Shape the paint, collage the shapes and make them form a painting

Masahiro Sekiguchi’s ‘Plane B’ at Kodama Gallery Tokyo

In Clyfford Still’s readymade, layered and collaged paintings (see my previous column), which call to mind walls upon which layers upon layers of posters have been pasted up and then removed, despite the fact that paint has been applied over the top of another painted surface, it appears the upper coat has peeled away to reveal the coat underneath. In other words, the application of paint generates the appearance of an undercoat, which can be equated to the generation of layers. Here, the jagged shapes signify clefts in the top coat. Because Still has used the same cleft shapes over several works, we know that they were by no means improvised, indeterminate shapes but rather specifically chosen shapes that were vitally important in the generation of layers.

The description “readymade, layered and collaged” also applies to the paintings of Masahiro Sekiguchi. They are readymade in the sense that they are prepared in advance, layered in the sense that they use thin films of paint, and collaged in the sense that Sekiguchi creates paintings by affixing to a canvas several “coats” made by applying oil paint to sheets of FRP and peeling it off before the paint has completely dried, like yuba (a delicacy made from the skin that forms on the top of gently-boiled soybean milk). The disparity between the visible, structural “layers” and the physical “coats” of paint, and the interaction between the two give rise to a unique form of painterly expression. At “Can’t See Well,” his 2009 debut exhibition at Kodama Gallery Kyoto, Sekiguchi took on the role of a “Pop” Clyfford Still (a contradiction in terms, perhaps) by creating walls on which “posters” in the form of thin coats of paint were applied one over the top of the other. In other words, he realized in a literal sense the effect one might receive from viewing Still’s paintings.

Masahiro Sekiguchi – Shinome (2009). The grey film of the topmost coat is literally torn to create the form.

Masahiro Sekiguchi – Shinome (2009). The grey film of the topmost coat is literally torn to create the form.At this point it would help to clarify the difference between non-physical phenomena and physical objects, that is, between layers and coats of paint, between form and shape. For example, when Gerhard Richter uses a squeegee to create “overlays” that are quite different in texture from the blurred “base” over which they are applied, a single transparent surface (a layer) is formed between the base and the underlay. Here, the layer is a non-physical phenomenon arising from the gap between the bottom and top layers. However, even in the case of Richter’s abstract paintings that consist of several layers, if one were to peel back the paint one would find just a single coat. Layers and coats are not the same thing.

Next, whereas “shape” refers to the outward appearance or contours of any given object, “form” is a phenomenon inside the brain that involves new recognition. Because this new recognition occurs based on a certain plane of relationships (or meaning), the new recognition of form can be compared with the generation of layers of sorts. In other words, in some cases layers in the form of invisible zero planes are generated from the gap between the base and the overlay, while in others they are generated as the new recognition of form.

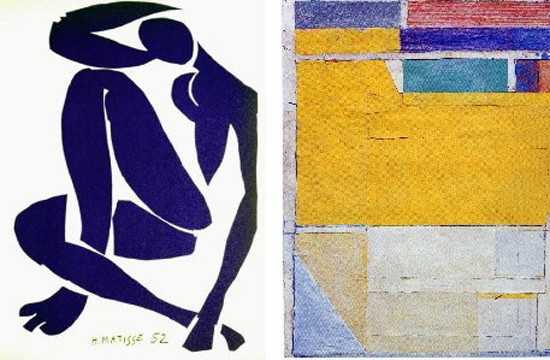

Layer and film/coat, form and shape and base and overlay are all intricately interrelated. Addressing the problem of form, Still has done no more than to offer an intuitive, simple solution. Pursuing the same problem more fully and multilaterally were the paper cut-outs of Matisse’s later years, and, following that, the collages of Richard Diebenkorn’s later years (1). Masahiro Sekiguchi’s recent exhibition at Kodama Gallery’s Tokyo branch, “Plane B,” took collage to an even further extreme by replacing Matisse’s colored paper with the more materialistic thin films of paint, dispensing with the pre-established harmony of “representation” altogether.

As is commonly known, when Matisse made his paper cut-outs, he cut out (and gave shape to) colored-paper sheets resembling layers, and collaged them, giving form (and thus generating a layer) to “sitting nudes.” These works constituted a unified form of line drawing and coloring (line drawing as cutting-plane lines dividing up the colored surfaces, and coloring arising from the divisional relationship of the colored planes). Layers, coats of paint, form and shape, base and overlay, coloring and line drawing: here in concentrated form are the problems addressed by painting as a form of expression. In other words, Sekiguchi has at his disposal a rich vein of precedent to mine.

Left: Henri Matisse – Nu Bleu IV (1952), gouache on paper cut out. Right: Richard Diebenkorn – Untitled (1992), synthetic polymer and pasted paper on board. Collection of the Hirshhorn Museum

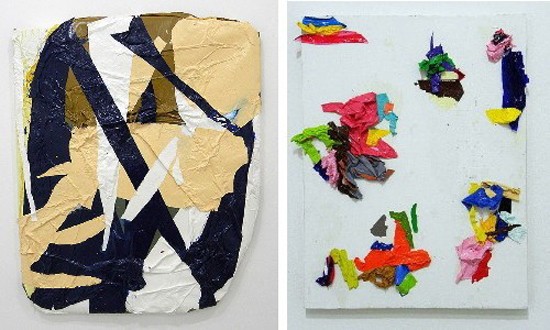

But what is this young artist mining from this rich vein? Depicting forms and affixing shapes is his starting point. He creates films, the two sides of which are different colors, by applying paint to sheets of FRP and then peeling it off. On supports upon which he has mounted aluminum foil, he affixes translucent films of translucent colors, giving the works an uncanny luster. Over the top of the collaged collection of shapes made of paint films he applies an additional coat of paint covering all or a part of the surface. He then traces the shapes of the affixed films with a brush, transforming them into “depicted forms.” By collaging multiple layers of these paint films he creates shaped canvases. He also peels off the paint films and affixes more films (ie, shapes) over the traces of the shapes (ie, forms) left on the canvas.

The collages themselves vary widely, from basic multilayering to carefree scattering, from flat collages to three-dimensional collages (2). Without having worked out his overall direction, the artist’s handling of the space between the layers and paint films, and shapes and forms is a bit all-inclusive and excessive, although the work does show that he hasn’t failed to consider the essential elements. As artworks, the pieces in the previous exhibition, “Can’t See Well,” at Kodama Kyoto were probably more accomplished. However, the work in “Plane B” is more immature, in a good sense.

Left: Atehoko (2010), oil on canvas, 77 x 63 cm. Right: Mico (2010), oil on canvas, 30 x 24.5 cm. Courtesy Kodama Gallery

Left: Atehoko (2010), oil on canvas, 77 x 63 cm. Right: Mico (2010), oil on canvas, 30 x 24.5 cm. Courtesy Kodama Gallery Simasan (detail, 2010), oil on canvas, 69 x 60 cm. Courtesy Kodama Gallery

Simasan (detail, 2010), oil on canvas, 69 x 60 cm. Courtesy Kodama Gallery Installation view of “Plane B” at Kodama Gallery Tokyo. Courtesy Kodama Gallery

Installation view of “Plane B” at Kodama Gallery Tokyo. Courtesy Kodama GalleryMasahiro Sekiguchi ‘s “Plane B” was on display at Kodama Gallery Tokyo, from February 20 to March 27,

-

The reason why Diebenkorn returned to figurative painting from the late 1950s to the early 1970s was that, unlike Still, he was unable to find satisfaction in intuitive painting, as a result of which the problem of form was difficult to resolve and stood in his way. In other words, as a painter he was starting again from 50 years earlier.

- These are for all intents and purposes ‘constructions’ made out of paint films.

Archive

Critical Fieldwork: Observations on Contemporary Art in Japan 1-6