From Karatsu, to Karatsu – The Adventures of Yasumoto Kajiwara (Part 2)

Hearing that Kajiwara favors using “materials and firing methods of the time,” you can imagine just how difficult the creative process is, but Kajiwara’s methods are always clear-cut and practical. (1) If one thinks about it it’s only natural, but regardless of how old the kiln was, as long as it operated in accordance with a standardized production system, it is inconceivable that the firing time was impractically long (three days and three nights! and so on) or that the processes were troublesome (a long drying time and so on). However, the easygoing rationalism that Kajiwara has discovered at the conclusion of his search not only dispels the spiritualism and aura built up by traditional Karatsu-ware masters (though this is something not limited to any particular style), but urges a rethink of the very nomenclature of ceramics.

For example, in the world of Japanese ceramics, earthenware is referred to as tsuchimono (lit. “earth objects”) and porcelain as ishimono (lit. “stone objects”). The rationale behind this is that earthenware is made of clay fashioned by kneading earth, and porcelain of clay fashioned from particular kinds of rock. However, for Kajiwara, who achieves the “sheen” of Karatsu ware from “rock,” this distinction is meaningless. In fact, as long as it is fired inside a kiln, organic earth (leaf mold, etc) does not present a problem, and because inorganic earth that becomes crisp when fired is simply weathered rock, ultimately earth is always already rock. (2) Rock is crushed and elutriated to extract the ingredients that become the clay, which is kneaded and shaped and coated in glaze before being fired. The distinction between “tsuchimono” and “ishimono” is meaningless, as is the distinction between the related terms “toki” (earthenware) and “jiki (porcelain). (3)

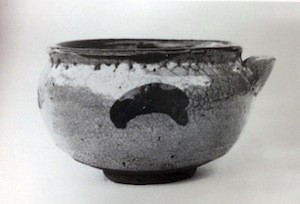

Yasumoto Kajiwara – Byakuren Ido tea bowl (Byakuren is an old kiln site where Ido ware tea bowls were made)

Yasumoto Kajiwara – Byakuren Ido tea bowl (Byakuren is an old kiln site where Ido ware tea bowls were made) Yasumoto Kajiwara – Todonri tea bowl (Todonri is also an old Ido ware kiln site)

Yasumoto Kajiwara – Todonri tea bowl (Todonri is also an old Ido ware kiln site) In the past there was a gap in Kajiwara’s ceramics. There was no painting or decoration. As mentioned earlier, Kajiwara’s concern is with reiterating the fundamentals of old ceramics as opposed to copying old ceramics. In other words, the forms and feet in his works resemble the style of old ceramics, but are in fact made in a way that is surprisingly unrestricted. However, the “pictures” in Ekaratsu (brush decorated Karatsu) and Gyeryongsan ware represent historical styles or motifs. To avoid sacrificing the beauty of Joseon dynasty or Karatsu ceramics, which everyone recognizes in such wares, or rather, to avoid turning them into pop paintings with no connection to Karatsu or Gyeryongsan, there is no alternative but to “copy” to a greater or lesser extent the designs and patterns seen in handed down works. (4)For this reason, as a devoted fundamentalist, Kajiwara only rarely tried his hand at painting or decorating, and even when he did in an attempt to realize contemporary Ekaratsu, in most cases the “pictures (?)” were the result of adding a single brushstroke in an extremely diffident manner. (5)

Yasumoto Kajiwara – Ekaratsu tea cup

Yasumoto Kajiwara – Ekaratsu tea cup Yasumoto Kajiwara – Left: Ichinose Ekaratsu plates. Right: Ekaratsu sake cups

Yasumoto Kajiwara – Left: Ichinose Ekaratsu plates. Right: Ekaratsu sake cupsHowever, at the exhibitions of new work by Yasumoto Kajiwara that began in January 2014 and were held in three locations in Tokyo and Osaka in June (6), a new trend towards the more active use of painting/decoration can be seen. As with the forms that are made freely while remaining true to the style of old ceramics, here Kajiwara seems to be cultivating a balance in his unrestrained “pictures” and engraved designs that are reminiscent of Ekaratsu, Gyeryongsan and Ding ware without being “copies.”

Yasumoto Kajiwara – Gyeryongsan sake bottles

Yasumoto Kajiwara – Gyeryongsan sake bottles Yasumoto Kajiwara – Ekaratsu large plate

Yasumoto Kajiwara – Ekaratsu large plateIn short, these somewhat unfathomable “pictures,” which are Gyeryongsan but by no means something you would see in handed down Gyeryongsan, are abstract writing. The pictures on Old Karatsu ware are normally something concrete (scouring rush, pines, grapes, etc) that has been turned into a pattern, and to this extent they are a kind of abstraction, but in Kajiwara’s case one could probably say that the abstraction has been pushed to the point where the concreteness has virtually disappeared. If traditional painting involves describing a pattern along the line of contact between the tip of the brush and the vessel’s surface, then Kajiwara’s painting involves moving the vessel’s surface slightly away from (dripping from the tip of the brush = a kind of pouring) and towards (painting with the middle of the brush = compressing the design) the tip of the brush, as if adjusting the focus of a camera back and forth, as it were. Out of this balance resulting from failing to bring the patterns into focus arise “pictures” infused with a surprising degree of humorous lightness for elements that are so bold.

-

Needless to say, just as not just anyone can realize the flavors of a first-rate chef if given the recipe, not just anyone can make clay from rock and fire it by following Kajiwara’s methods. This is because there will always be intuitive skills and devices that cannot be turned into a recipe.

- However, there is a difference between mountain soil in the form of weathered rock (which retains its mineral contents) and paddy soil, which is mountain soil that has been washed downstream by rain and accumulated over many years (from which most of the mineral contents have drained out). This is the reason why the old Bizen kilns where mountain soil was used practiced oxygen-reduction firing, but switched to oxygen-rich firing after they started using paddy soil.

- The Japanese term “jiki” is nothing more than a colloquial one in which the first character from the Chinese placename Cizhou, of Cizhou ware fame, is combined with the character for “vessel,” in a similar way to how the Japanese placename “Seto” is combined with the character for “object” to produce the term “setomono,” meaning “ceramics.” In China, the equivalent term “ciqi,” which uses a different first character, essentially refers to a vessel that has been glazed and biscuit fired at a high temperature, with other forms of ceramics referred to as “toki.” In other words, what we in Japan call “doki” (unglazed earthenware) is called “toki” in China, and what we call “toki” and “jiki” are both called “ciqi” in China. In Korea they also have the category “sagi.” Many translators struggle over this lack of correspondence among the ceramics terminologies in Japan, China and Korea. See for example “Nihongoban no kanko ni atatte” (On the publication of the Japanese edition) in the Japanese edition of Chugoku tojiki tsushi (A complete history of Chinese ceramics) (Heibonsha, 1991) compiled by the Chinese Ceramic Society.

- Kinichi Furutachi, Ekaratsu monyoshu (A collection of Ekaratsu designs) (Ribunshuppan, 2010), etc.

- Although such minimalistic painting can occasionally be seen on Old Karatsu ware.

Ekaratsu lipped tea bowl from Ekaratsu monyoshu (A collection of Ekaratsu designs)

Ekaratsu lipped tea bowl from Ekaratsu monyoshu (A collection of Ekaratsu designs) - “Karatsu: Yasumoto Kajiwara,” Gallery Sho, Osaka, June 6 through 14; “Karatsu: Yasumoto Kajiwara,” Shibuya Kurodatoen , Tokyo, June 20 through 24; and “Karatsu: Ceramic works by Yasumoto Kajiwara,” Tobu Ikebukuro, Tokyo, June 19 through 25.