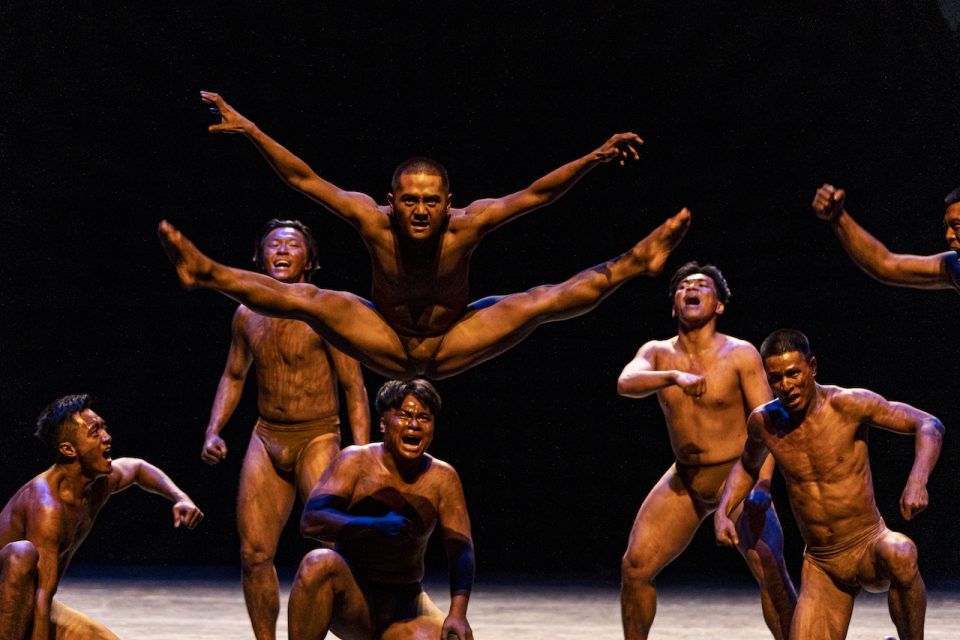

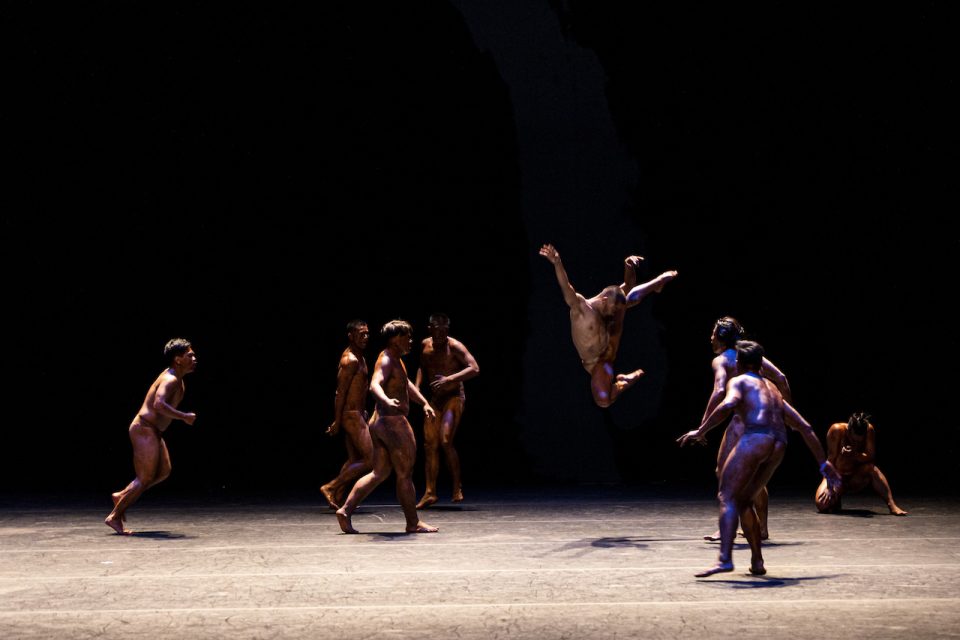

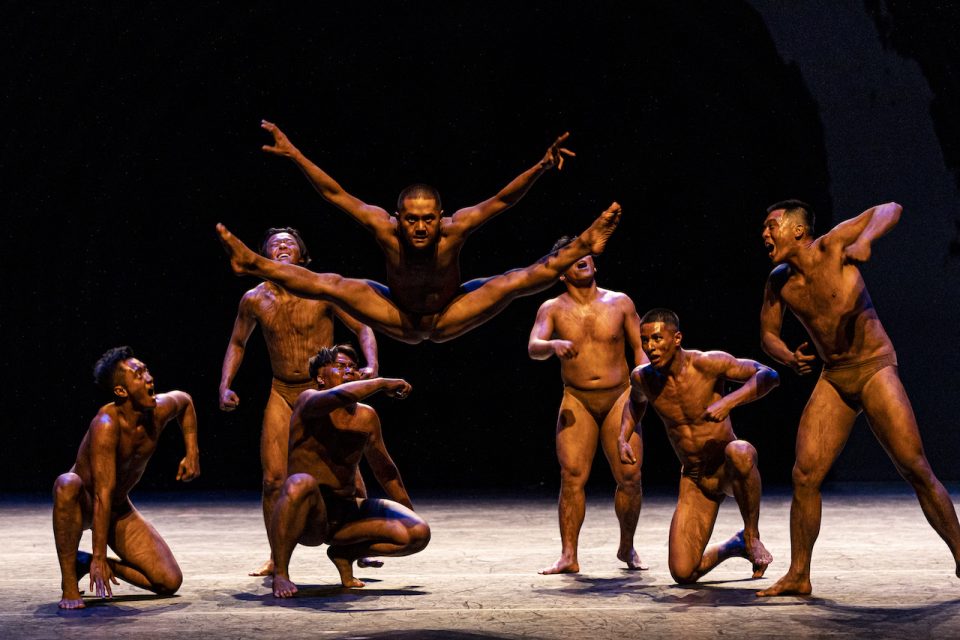

Bulareyaung Dance Company – LUNA, Yokohama International Performing Arts Meeting 2022 (YPAM2022), KAAT Kanagawa Arts Theatre, Hall, 2022 Photo: Hideto Maezawa

Bulareyaung Dance Company: LUNA

The Bunun tribe and dancers—mutual giving and bestowing of life forces

Miwa Yanagi

Translation: Haruko Kohno

Bulareyaung Dance Company (布拉瑞揚舞団)

Founded in 2015 by Bulareyaung Pagarlava, a choreographer of Paiwan descent from Taiwan, the Bulareyaung Dance Company has won many awards both at home and abroad and is garnering worldwide attention in recent years. LUNA is the culmination of the encounter between the Bulareyaung Dance Company and the indigenous singers of the traditional Bunun chant, performed as the first full-length dance performance by the Company.

Bulareyaung Pagarlava

Born in Taitung, Bulareyaung is from the Paiwan tribe of Taiwan. He aspired to become a dancer at the age of 12 and left home at the age of 15 to pursue further studies under a Han name, but reassumed his Paiwan name when studying dance at the Taipei National University of the Arts. Upon graduating, he joined the Cloud Gate Dance Theatre.

In 1998, Bulareyaung was awarded the Performing Arts Fellowship from the Asian Cultural Council to further his dance studies in New York. Multiple dance companies have performed under Bulareyaung’s choreography, which has earned him international recognition. The seeds of dance that he planted in the east coast of Taiwan are being presented through various works to audiences across the world.

The Bunun indigenous people (布農族)

The Bunun currently numbers a little less than 60,000 people. They traditionally lived in the high mountain areas but were forced to move down to lowland villages across the Nantou, Hualien, Taitung, and Kaohsiung Counties due to colonial policy during the period of Japanese rule. Hunting was also restricted at this time(1), and the slash-and-burn agricultural practice (of millet and taro, etc.) was converted mainly to paddy cultivation. The people of Bunun speak the Bunun language. Like other Taiwanese indigenous peoples, the “sun shooting legend” and the “flood legend” have been told among the Bunun people. The word Bunun literally means “human.”

LUNA Bulareyaung Dance Company, Interview with Bulareyaung Pagarlava for the 17th Taishin Arts Award

Bulareyaung Dance Company – LUNA, Yokohama International Performing Arts Meeting 2022 (YPAM2022), KAAT Kanagawa Arts Theatre, Hall, 2022 Photo: Hideto Maezawa

Chorus in the dark, singing bodies

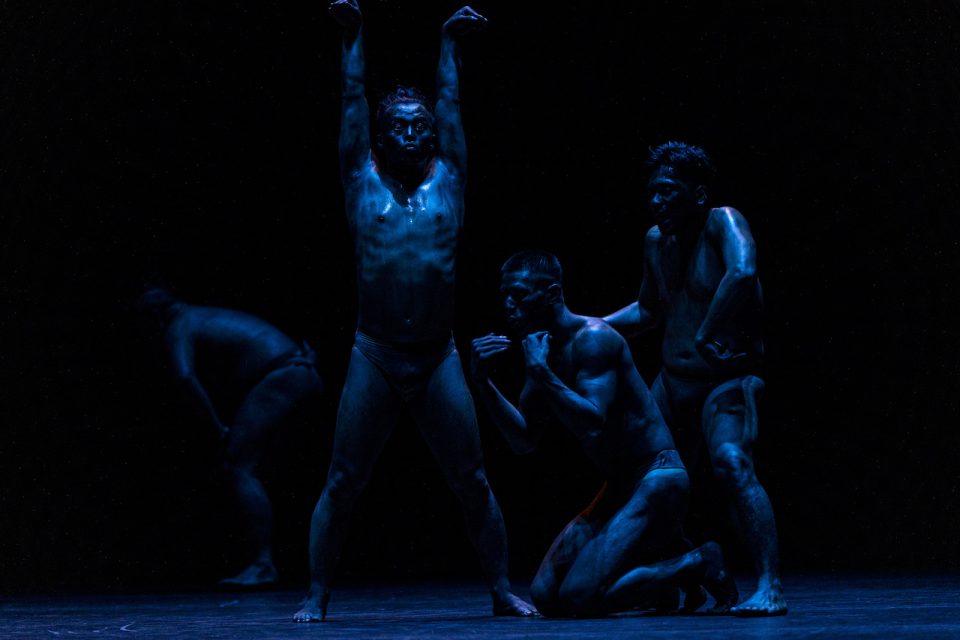

Singing voices of men resonate from beyond the darkness. Voices call upon one another from different directions amid the mountains in the middle of the night, perhaps to signal the beginning of a ritual or the return of hunters. The atmosphere of a mountainous forest at night permeates the theatrical space.

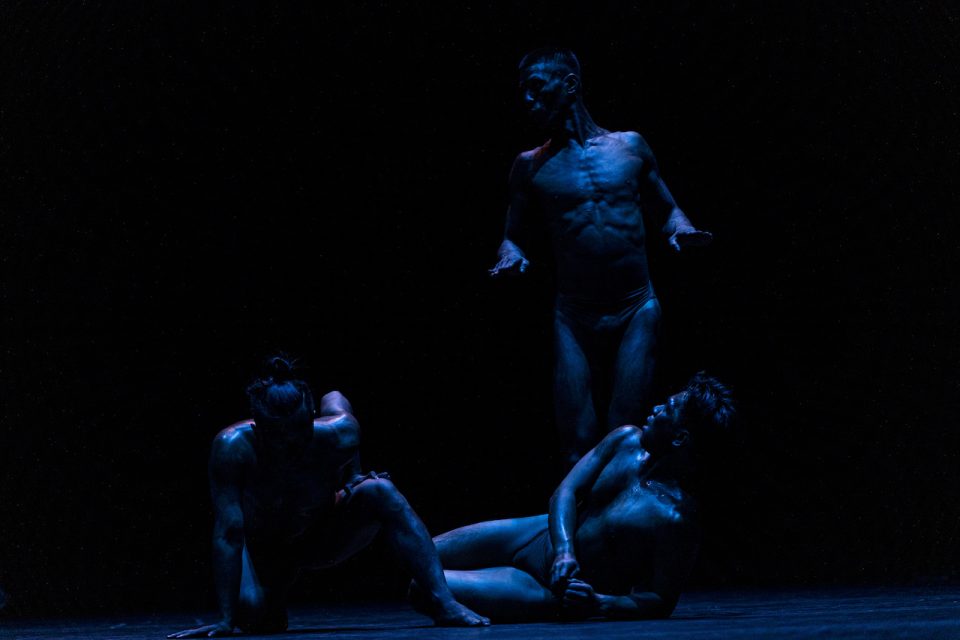

Before long, flickers of light pierce through the darkness as the singing men come down the slope of the mountain (the aisles of the seating area) and gather in the open space (on stage). Their tanned skin is exposed but for a loincloth wrapped around the waist, and the headlamps they wear illuminate one another in the darkness. The men march in line, come together as a group, or form a ring. One moment they are walking like hunters with their heads held low, the next they get down on all fours and run around like beasts. To one’s surprise, they dance and leap energetically, while singing, talking and shouting, from beginning to end. At times, the songs they sing are melodious and tranquil, while at others, there are roars proclaiming victory like the haka before a rugby game.(2) The lighting and the projection on stage were delicately and beautifully executed while the choreography showed the vibrant bodies of the men constantly moving in the forest, the river, and nature.

An encounter with the Bunun tribe

Bulareyaung and his fellow dancers paid a visit to the village of the Bunun, one of the tribal peoples of Taiwan, where they heard by chance their traditional song chants. Deeply moved by the chanting, they decided to temporarily move to Luluna, the largest village of the Bunun tribe in Taiwan at an elevation of 1,000 meters above sea level. There they studied the unique singing method from the tribal elder and the “Luluna Bunun Choir,” a group that carries on the heritage of Bunun tribe music, and also mastered the rituals and movements of the mountain hunting people. By sampling these elements in the composition, Bulareyaung aimed for a fusion of indigenous traditions and contemporary dance in the production LUNA.

The Bunun traditionally were high mountain people living on the Central Mountain Range, but from the Japanese colonial period onward, they settled in lowland villages in counties such as Nantou, Hualien, and Taitung, in central Taiwan. The tribe is known worldwide for the unique tradition of the “eight-part polyphony” that has been handed down through generations. (This type of chorus sung as prayers for an abundant harvest is called pasibutbut in the Bunun language.) A group of six to twelve chosen individuals (the number must be even) form a circle in the open air, hands placed on the hips of each other, and sing together while slowly moving in counterclockwise direction. The group is separated into four parts but each individual sings polyphonically, making it an eight-part polyphony. The pasibutbut is a complex harmonic style where the singer’s bodily movement during the singing causes a fluctuation in the voice. There is also a mystical side to the practice as there are many taboos associated with it, such as the restriction of singing to harvesting season. As is the case of other ethnic groups, there have been generational breaks in the handing down of the tradition, leaving some young people unable to speak the language or sing the songs of their place of origin.

Bulareyaung and his fellow dancers sought and obtained permission from the tribal elder to recreate a new form of expression from this tradition. To begin with, these traditional songs, sung as a way to boast one’s prowess in battle or hunting, originate from the ancient Bunun way of life and culture, which makes it difficult for young dancers coming from different origins to relate to them. Hence, when performing the “exploit-boasting” songs, the dancers tried to grasp the essence by singing instead lyrics about the struggles and challenges in their own lives or about their own identities. “I started to learn how to dance at a young age. It required a tremendous amount of effort and I injured myself quite often…” Upon hearing such monologues sung by each dancer, the tribal elder and villagers were evidently deeply moved.

LUNA Bulareyaung Dance Company, The “eight-part polyphony” (pasibutbut in the Bunun language)

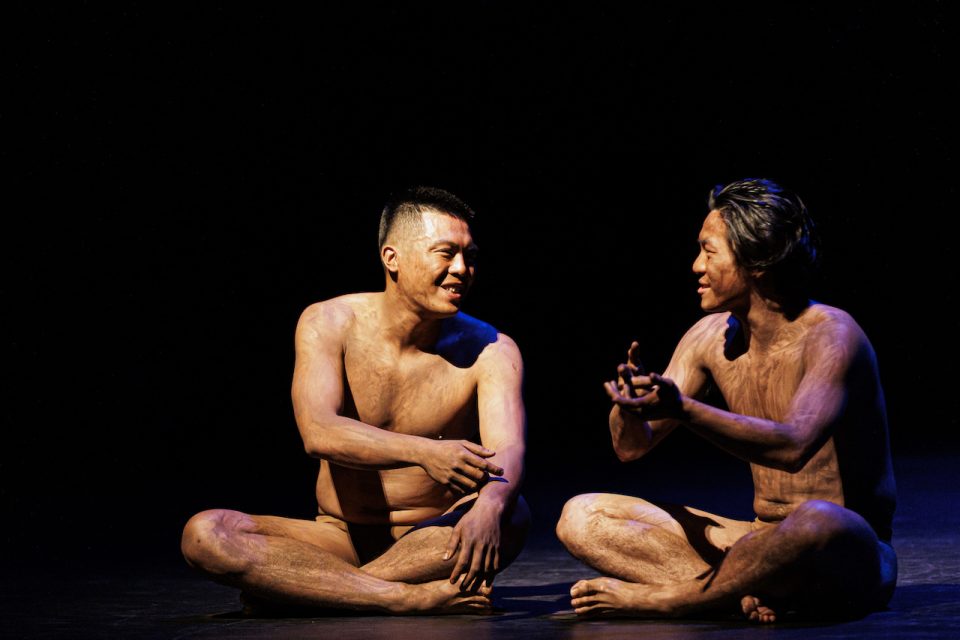

A rather unusual conversation has also been incorporated in LUNA. It is an exchange of questions and answers on the theme of hunting. Two dancers sit down for a long chat. One says, “We cannot stop hunting because it is rooted in our traditional culture.” To this, the other argues, “No, there is no need to enter the mountains to kill an animal at the risk of one’s life. You can buy meat at the supermarket. Traditions should change with the times.” In this dialogue that takes the style of a documentary reenactment, Bulareyaung presents the relationship between tribal villagers and outside visitors like himself from an objective perspective. Hunting, a lifestyle that was once commonly practiced, has been lost, while the song and dance associated with it have prevailed. This begs the question—should people try to bring back lifestyles that are now obsolete or should they pass down the songs and dances recreated as new forms of expression by breathing new life into them? What unfolds here is a fundamental question concerning the succession of tradition. Of the dancers engaged in conversation, one is from the Puyuma tribe that carries on the hunting tradition, and the other is a Han Chinese who has no experience in hunting.

The monologue-like singing and the conversational drama by the dancers are perhaps some of the gems and stones Bulareyaung and the dancers found in the tribal village and polished through the creative process. These are likely taking place for the audience to feel the transition of the human body from the “hunting body” to the “non-hunting body.” Here one can feel the Bunun people’s wholehearted approval of the dancers’ creative approach and their generosity in opening up the tradition to the outside world. The people involved are breaking the mold of the conventional Bunun song and dance, just slightly so as to embrace a new form of expression. In LUNA, the Bunun tradition can be carried on, or developed further into something else to be transmitted to the world. What is happening here is a spontaneous and mutual giving between the traditional performers of Bunun and the dancers, all engaged in their respective forms of expression.

It goes without saying that this sort of relationship could not have been built overnight. It owes to the long history of preservation and inheritance of tribal performing arts in Taiwan.

Bulareyaung Dance Company – LUNA, Yokohama International Performing Arts Meeting 2022 (YPAM2022), KAAT Kanagawa Arts Theatre, Hall, 2022 Photo: Hideto Maezawa

Bulareyaung Dance Company – LUNA, Yokohama International Performing Arts Meeting 2022 (YPAM2022), KAAT Kanagawa Arts Theatre, Hall, 2022 Photo: Hideto Maezawa

The thriving performing arts of indigenous peoples

The collection and transcription of the music and dance of indigenous Taiwanese peoples began when Taiwan was still under Japanese colonial rule. The comprehensive survey and recording by the musicologist Kurosawa Takatomo at the end of the colonial period in 1943 counts among the most important materials that remain today.(3) After World War II, as the Chinese Nationalist Party took control and Christianity flourished, there was a gradual hollowing-out of the music and dance of indigenous peoples. By around 1970, the tradition lapsed into a kind of dance show for tourists, some of which were stereotyped and flavored with elements of entertainment. Gradually, however, as Taiwan began to regain its historical subjectivity and nationalist movements intensified, people began to reevaluate the ethnic cultures of Taiwan. In the 1980s, the younger generations who had left their hometowns and villages to live in cities began to launch learning environments with the aim of succeeding the ethnic arts and culture of their origins. In order to carry on the near-obsolete traditions, they learned the songs and dances orally from the elders, faithfully recreated ceremonies and rituals, and further refined the dynamic dances. Scholars of traditional cultures and professional dancers were summoned to take part and to recreate the ceremonial and ritualistic performing arts that were traditionally held in villages into contemporary “stage productions” in the best way possible. This led to the formation of the Formosa Aboriginal Song and Dance Troupe, a dance ensemble that draws its performers from different native tribes in Taiwan. The group was later formally reestablished as a performing arts company, the Formosa Indigenous Dance Foundation of Culture and Arts (the head office is currently located in Hualien County). The Foundation continues to be actively engaged in the dissemination of traditional cultures and exchanges with audiences in Taiwan and across the world.

Researchers believe that the dances, songs and musical performances of indigenous peoples are the “texts” of the respective cultures, in the same way that history is recorded in the form of written words. Their contribution, driven by this strong belief, has been very significant.(4)

Having said that, the performances by the Formosa Aboriginal Song and Dance Troupe compile elements extracted from the music and dance of different individual tribes, and thus symbolize a pan-tribal consciousness transcending ethnic boundaries. This broad consciousness of ethnicity is something that has been nurtured mainly among the tribal peoples living in urban areas (which is said to be approximately more than half of the indigenous population today). Today, there are quasi-tribal settlements in cities that take the form of artist colonies where people of various ethnic groups congregate, while an increasing number of tribal artists are also creating literature, music and dance as they go back and forth between cities and their tribal homelands. Needless to say, tribal cultures are not heritages of the past but living, breathing cultures that continue to change with the people.

Bulareyaung Dance Company – LUNA, Yokohama International Performing Arts Meeting 2022 (YPAM2022), KAAT Kanagawa Arts Theatre, Hall, 2022 Photo: Hideto Maezawa

Bulareyaung Dance Company – LUNA, Yokohama International Performing Arts Meeting 2022 (YPAM2022), KAAT Kanagawa Arts Theatre, Hall, 2022 Photo: Hideto Maezawa

Singing Voices and Written Text

In LUNA, subtitles are not provided to the audience. Instead, the song lyrics and the dialogues are handed out as printouts along with the pamphlet on the day of the performance. Had I not read these preliminary materials and listened to Bulareyaung’s impassioned commentary before the performance, I may have mistaken it as a traditional dance by men of the indigenous Bunun tribe, at least up until the introductory part, as this was my first viewing of a performance by the Bulareyaung Dance Company. I suppose foreign audiences would assume that these were original songs and dances of an indigenous Taiwanese tribe performed on stage by the aforementioned Formosa Aboriginal Song and Dance Troupe. It’s not clear to the audience whether the dancers are singing the traditional songs of the Bunun tribe or talking about their own lives. Perhaps the more ardent a viewer is, the more they would want to follow subtitles for a deeper reading.

Deciding on whether or not to provide audiences with subtitles requires a lot of consideration, especially when it comes to theatrical performances where the emphasis in on the physicality of the performers. This is and has always been an agonizing issue for writers and production staff. There is always the risk of changing the essence of the work once a performer’s utterances on stage are converted to text. Especially with LUNA, it’s easy to imagine how captioning the lyrics of the Bunun tribe who have no writing system can be problematic; whether in Chinese, English or Japanese, the subtitles are likely to dramatically change the nature of the work. Therefore, I think it was a brave decision not to add subtitles to this work.

At the same time, I have always been under the impression that in Taiwan, people are cautious about captioning voices with subtitles or transcribing voices into text, at least more so than in Japan. This was something I also felt when I wrote and directed a Taiwanese Opera (popular folk opera sung in Taiwanese) in Taiwan. We discussed the possibility of offering subtitles in Chinese (Mandarin) as not all Taiwanese people understand the Taiwanese (Hokkien) spoken on stage. After much discussion, it was decided that Chinese subtitles would not be projected on stage. One of the reasons for this was because the Chinese characters in written Hokkien are yet to be standardized and problems could arise from the specific choice of characters. While listening to this discussion, I was overcome by this feeling that the significance of Chinese characters had all of a sudden become uncertain, which was a valuable experience. It was as if we had gone back even before the time when the Manyoshu (a collection of waka poetry which used only Chinese characters to phonetically express Japanese) was written, and a world consisting solely of rich sounds was emerging before me.

Apparently, Bulareyaung and his fellow dancers asked the Bunun people to sing their songs and then diligently transcribed the lyrics in Pinyin as they listened to them. I am certain that from there, they embarked on a long journey of converting the singing voices into written text through trial and error.

The dancers’ act of transcribing the songs of the Bunun tribe may have arisen from their own need to remember the songs, but it is those small, personal “needs” which become the impetus for developing a writing system for a language. From there, it takes the tremendous power of a nation and a long time for letters to be systematized into an established writing system. However, in the past those efforts eventually became a surge in the river and engulfed many preliterate cultures. Bearing this in mind, we could say that the dancers may have felt that jotting down the lyrics in Pinyin on small pieces of paper were like the first droplet of that surge.

Speaking of a genre that is slightly different from singing voices, historically, the indigenous literatures of Taiwanese tribes who did not have their own writing system could only have originated through the intermediary languages of Japanese, followed by Chinese, which were languages enforced upon the people of Taiwan. We could say that songs and music have more freedom than literature as they traverse both sound and text.

Legend has it that the Bunun and the Amis peoples did in fact have writing systems in earlier times. The Bunun legend recounts that in ancient times, letters fell from the sky and were received and used by people in daily life, but were all washed away and lost when a flood occurred. Similarly, in the case of the Amis, letters are said to have sunk and disappeared under water. Both legends are suggestive, perhaps indicating that permanent, absolute archives do not exist.(5)

Bulareyaung Dance Company – LUNA, Yokohama International Performing Arts Meeting 2022 (YPAM2022), KAAT Kanagawa Arts Theatre, Hall, 2022 Photo: Hideto Maezawa

Bulareyaung Dance Company – LUNA, Yokohama International Performing Arts Meeting 2022 (YPAM2022), KAAT Kanagawa Arts Theatre, Hall, 2022 Photo: Hideto Maezawa

Believing that someday people will understand

“I’m definitely sure you will love the songs.” This is what Bulareyaung told audiences at his talk right before the performance. At this preliminary talk, he spoke energetically in one breath about the encounter and eventual collaboration between the Bulareyaung dancers and the wonderful songs of the Bunun tribe. He concluded with a smile, “Because of the language difference, Japanese audiences may find it difficult to understand the piece, but I’m a firm believer that if you really put your heart into something, people will understand. I’m definitely sure you will love the songs.” Bulareyaung feels that performers shouldn’t impatiently depend on words because they can’t get their message across or out of fear that people won’t understand. He prefers to think that “…someday, people will understand.” I think there is something common between his creative style and the benevolence, magnanimity, and openness of Taiwan that many Japanese people feel upon their visit.

Just as Audrey Tang is a self-described “conservative anarchist,” Taiwan itself is a place where a distinct air of anarchism and respect for traditional values coexist. By anarchism, I do not mean the rejection of a government authority nor a revolutionary mindset, but the kind of ideology that aims for a way of living based on a spirit of cooperation that is not enforced by power. And by conservative, I mean having respect for tradition and valuing environments where one’s dignity is not being violated. In earlier times, various rulers from mainland China, Europe, Japan and elsewhere crossed oceans and set foot on the Taiwanese island, subjugating the indigenous peoples under their name. As a result, Taiwan today has a complicated profile as a nation where twenty tribes, languages, and a diverse mix of values coexist on one small island. To go about one’s daily life in contemporary Taiwan, it is almost a prerequisite to understand that people should not threaten each other’s existence and force upon others what they believe is the only right way. Tolerance of others is only possible where one’s tradition and life are being protected. Encounters with others are not always comfortable. Disagreements may arise when different people engage in collaboration to create something. Each side must change little by little, making compromises along the way. Moreover, if the country is in support of this coexistence, the artists will be able to flourish in their respective fields and their efforts will bear fruit. Indeed, the Bunun people and the young dancers gave each other all that they had in good faith and engaged in a generous exchange of their life forces. LUNA was the valuable fruit of that exchange.

Bulareyaung choreographs a very diverse range of works. In one work, for example, he proclaims to transcend the gender barrier by presenting male dancers performing in heels, which is a complete change of style from LUNA. I hope that in the near future, the Bulareyaung Dance Company will once again surprise Japanese audiences with their groundbreaking (and once again, anarchistic!) performance.

Bulareyaung Dance Company – LUNA, Yokohama International Performing Arts Meeting 2022 (YPAM2022), KAAT Kanagawa Arts Theatre, Hall, 2022 Photo: Hideto Maezawa

LUNA Bulareyaung Dance Company

*1 Currently, hunting is permitted upon request.

*2 Haka, noted as the ceremonial performance by New Zealand’s national rugby team prior to each match, originates in the dancing and shouting performed before a battle by the indigenous Maori people to display unity and strength. It is a kind of performance whereby the individuals shout out a battle cry to fire up warriors on a battlefield, equivalent to the Japanese toki-no-koe. Besides New Zealand, haka takes various forms of dance in regions across Polynesia, and in recent years, an increasing number of countries have come to perform the haka before a sports match. In fact, in the future, the trend of performing traditional dances may extend beyond Polynesia to other countries in the Pacific Rim.

*3 Sounds from Wartime Taiwan 1943: Kurosawa and Masu’s Recordings of Taiwan Aboriginal and Han Chinese Music, 2008, National Taiwan University.

*4 Chen, Chih-fan, “‘Gen’ kara uta ga atta—Taiwan genjumin bungaku/kayo no taiwa to bunka sozo—” in Taiwan genjumin no ongaku to bunka [Taiwan Indigenous Peoples Music and Culture], eds., Shimomura Sakujiro, Sun Ta-chuan, Ling Ching-tsai, Kasahara Masaharu, 2013, Sofukan.

*5 ibid.

LUNA

Bulareyaung Dance Company

3 DEC 2022 (Sat)18:30-19:50

KAAT Kanagawa Arts Theatre, Hall

https://ypam.jp/programs/dr79

Cooperation:Yokohama International Performing Arts Meeting 2022 (YPAM2022)

Miwa Yanagi

Studied at the Department of Crafts at the Kyoto City University of Arts. After showing works of photography and other media in domestic and international exhibitions, Yanagi represented Japan at the 53rd Venice Biennale (2009). Since 2011, Yanagi has also been active in theatre, presenting works in both art museums and theatrical venues. Zero Hour: Tokyo Rose’s Last Tape, toured five North American cities in 2015. Yanagi’s Wings of the Sun (based on the novel by Kenji Nakagami), an outdoor production performed on a traveling stage trailer made in Taiwan, has played in locations throughout Japan since 2016. In 2021, she was invited to create an opera with three major Taiwanese opera troupes in south Taiwan-—Shiu-Kim Taiwanese Opera Troupe, Chun-Mei Taiwanese Opera Troupe, and Ming Hua Yuan Tian Zi Art & Culture Group. The opera “Aphrodite” was performed in 2021 at the outdoor theater of the National Kaoshung Center for the arts.