Observations on Contemporary Art in Japan

Collage, Pop Art, Clyfford Still: Kaneuji Teppei’s Post-Something at Shugo Arts

White paintings, cloisonnism, coffee staining, and clippings of brushstrokes and touches of paint… or in other words painterliness; and seals, figures, driftwood, pipes, and wrapping paper… or in other words readymade – Kaneuji Teppei’s artworks quite clearly relate to a Duchampian context. Modern art has evolved by critiquing existing ‘art’ and aiming for ‘something’ undifferentiated and undefined by society. Art criticism requires an awareness that true art must not be contrived and that the artist must do as little as possible. ‘Readymade’, in which the artist literally does nothing, is regarded as ‘something’ that can have no meaning or taste or value within society and occupies a position of the purest kind of artwork in the form of objects that exist in a vacuum as it were. Which is why if one pursues the pure identity of media such as ‘painting’ and ‘sculpture’, scraping away impurities to the greatest possible extent, the problem of readymade (‘a plain white canvas’) always presents itself.

Many of the installation artists who use everyday objects in this Duchampian context tend to think in a Cage-like fashion, as it were, because the everyday is so fertile as it is, there is no need for the artist to take it upon themselves to make anything; they need only present events as they occur daily (or the complete opposite of this in the form of absolute artificiality). This tendency, which is characterized by the extremes of ‘cynical production + a return to the base of the everyday’, ultimately arrives at the modern dualism of ‘the system + everything outside it’, or in other words it is nothing more than the conscious transformation into artwork of ‘absorption into the base’. In contrast to this, Kaneuji’s works gradually break apart this modern bipolarity through the relentless overturning of basal elements. The top becomes the bottom, and the bottom the top, so that top and bottom no longer exist; the land becomes a map, and a map becomes the land; the support or frame becomes the artwork, and the artwork becomes the support or frame; and so on and so forth.

This is why Kaneuji returns again and again to the new and old method of ‘collage’. Collage is the negation of the void. The process of exposing background/basal elements whose existence is unconsciously taken for granted – blank space, zero, transparency, nothingness, emptiness, unconsciousness, the everyday – and pouring cold water on the absorption into the zero state (= base) that presents itself is on the boundaries of modernism; this is collage. It is the ‘movement of the supplement’ (Derrida) and the deconstruction of the base, but it also has something in common with Pop Art. A good example of this is Roy Lichtenstein’s Brushstrokes series, in which the artist sampled furious brushstrokes that arose by chance out of the unconscious act of painting and transformed them into absurd paintings and monuments(*1).

Roy Lichtenstein Tokyo Brushstroke I (1993)

Roy Lichtenstein Tokyo Brushstroke I (1993)As noted previously in this column (see 2: From Collage, To Collage), collage involves the creation of 1) elements that form the base (layers, supports, frames, floors, pedestals), 2) a crossover between two and three dimensions, and 3) a frame of meaning. Because each time a frame of meaning is created both 1) and 2) are renewed in succession, there is no end in collage(*2). To express blank space, zero, unconsciousness, and the everyday in concrete terms that correspond to Kaneuji’s artworks, a) blank space is what is left when seals and figures are removed, surplus resin that has dribbled down onto the floor, the paper that remains after clippings have been removed; b) zero state is white color, transparency, patterns on floors or walls (wood grain); c) unconsciousness is unconscious brushstrokes (automatic writing), staining, etc.; and d) everyday is readymade everyday items(*3). Although the materials used vary widely (depending on the scale of the home center from which they are sourced?), the artworks are always created consistently in accordance with a multilayered/composite construction that takes the form (1-3) x (a-d).

For example, in the The Eternal (wood grain pattern), a wall (or floor) forms the image, while clippings of cream images = touches of paint serve as the frame (1, c, d, 3). In The Laws of Framing, an actual sheet of wood is leaned up against a white wall and the surface collaged over with clippings of paper printed with wood grains and white paper before being combined with wooden frames (1, 2, a, d, 3). In Model of Something, the transparent material that served as the pedestal for Day Tripper, in which brushstrokes have been given three-dimensional form, is in turn placed on a pedestal and covered in brushstrokes (1, b, c).

Kaneuji Teppei The Eternal (Pattern of Wood grain #1) (2010)

Kaneuji Teppei The Eternal (Pattern of Wood grain #1) (2010) Kaneuji Teppei (from left) Ghost in the Liquid Room #4, Day Tripper (Sculpture of photograph of paint), Tower of Something #2, Model of Something (2010)

Kaneuji Teppei (from left) Ghost in the Liquid Room #4, Day Tripper (Sculpture of photograph of paint), Tower of Something #2, Model of Something (2010) Kaneuji Teppei The Laws of Framing (2010)

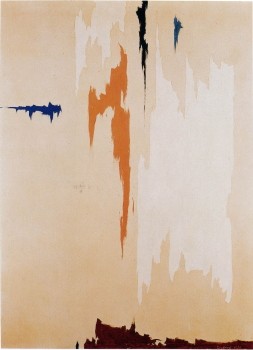

Kaneuji Teppei The Laws of Framing (2010)The most painterly thing in this exhibition is the complex collage work visible in Ghost in the Liquid Room #4 and The Eternal (Various Pattern). The wallpaper and wrapping paper stand as readymade products for layers; that is, these are the same, Kaneuji-style layered collages. As readymade layered collages, these pieces have much in common with the paintings of Clyfford Still. Still’s paintings(*4), which were in turn influenced by Monet’s later work – paintings that included layers in the form of surfaces of water – are also readymade (it’s known that his indeterminate brushstrokes were actually repeated over multiple works like stencils)(*5), layered (he may have been inspired by wall surfaces on which posters or wallpaper had been repeatedly pasted and removed), and collaged (his treatment of the edges of his canvases indicates he was conscious of framing). They are paintings in which the areas that have been painted over appear to be peeking out from behind, in which figure and ground, top and bottom are continually being overturned.

Clyfford Still Untitled (1955)

Clyfford Still Untitled (1955) Kaneuji Teppei: Recent Works “Post-Something”

2010.1.16 – 2.27

ShugoArts (Kiyosumi)

http://www.shugoarts.com

-

In contrast to Lichtenstein’s Brushstrokes, which represents a commentary on heroic creative acts that daringly open up to spontaneous chance (Pollock’s pouring is a typical example), the three-dimensionality of whose strokes therefore stands out in an almost phallic manner, works such as Splash and Flake (Pipeline #3) and Day Tripper, while also taking the form of three-dimensionally rendered brushstrokes, are rather collages of brushstrokes that more closely resemble automatic writing or spontaneous graffiti than action painting.

- Hence the use of the term ‘dimensions variable’ to describe several of the works.

- Although Kaneuji often uses cheap advertisements and advertising material (complementary candy, etc.) in his works, this is not the same as ‘kitsch’, in which modernism introduced and employed everyday items or mass-produced products as ‘something’ outside of the system called art. This is because in today’s society a dialectic between high art and low art is impossible. For more on kitsch and collage, see Rosalind E. Krauss, The Picasso Papers, Chapter 2.

- Greenberg points out this, as well as the existence of popular elements such as wallpaper and posters in Still’s work, in “American-type Painting” (1955) and “Influences of Matisse” (1973). See Clement Greenberg: The Collected Essays and Criticism Vol.4.

- See Neal Benezra, Clyfford Still’s Replicas. Clyfford Still 1944-1960, Yale University Press, 2001, p.87ff.

Shimizu Minoru: Critical Fieldwork Index

ART iT Snapshot: Kaneuji Teppei Recent Works ‘Post-Something’

ART iT ArtPartner: ShugoArts