2009.6.24 – 9.7

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

http://www.moma.org

by Olivia Hampton

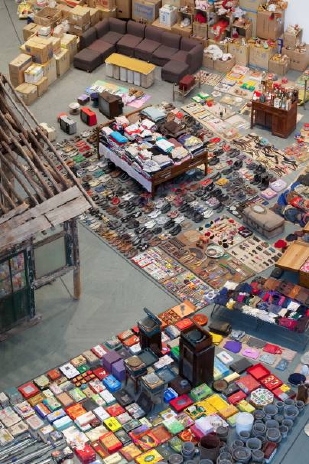

Installation view of Projects 90: Song Dong

Installation view of Projects 90: Song Dong at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, 2009

Photo Jason Mandella

“Dad, don’t worry, mum and we are fine,” begs a neon sign. It is a potent appeal Song Dong launched in Waste Not (2005), initially a collaboration with his mother to help her cope with his father’s death in 2002. Although Zhao Xiang Yuan (1938-2009) has now passed away, Song has brought the installation to the United States for the first time, a country known to waste much and save little.

A powerful counterpoint to the idolized consumerist culture so familiar today, the installation also reflects the Beijing-based artist’s recurring themes of impermanence and transience.

Littered across MoMA’s 3,000-square-foot (279-square-meter) Donald B. and Catherine C. Marron Atrium are countless objects Song’s mother collected in her home over the course of 50 years that experienced the trials and Spartan lifestyle that accompanied China’s Cultural Revolution.

A sea of pots, basins, cups, shirts, buttons, neckties, pens, handbags, stuffed animals, legless dolls but also the artist’s tiny Beijing childhood home itself are lined up in an intricate alternative cityscape with ‘alleys’ and ‘streets’, an invitation to explore the goods of the past that continue to fulfill Zhao’s wish to ‘waste not’ by living yet another life. Although Zhao died earlier this year, Song has kept his project in the family, now with the help of his sister, Song Hui, and his wife, Yin Xiuzhen.

The sense of security yielded by keeping and maintaining objects – then a requisite for survival, today seemingly superfluous – belongs to a time when many lacked in personal belongings but can still provide a lesson on how to save. These were precious possessions from which Zhao was not willing to part until her last dying breath.

Coping with loss was a big part of Song’s personal life, where his mother’s once wealthy family lost everything when a relative was jailed for spying against the Communist Party, while his father served several years in a forced labor camp after being charged with engaging in counterrevolutionary activities.

Standing tall above the goods, the viewer senses their fragility, how easily they could be quashed but also reveal intimate fragments of a long lost life and the delicate beauty of the everyday.