Naked Photography: Takuma Nakahira’s ‘Documentary’

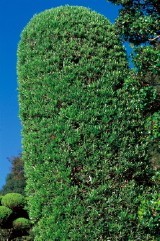

Left to right: Images of “tactile surface layers” (2007), (2009), (2007).

In photography, every common noun becomes a proper noun, every being becomes “this,” and in this thisness, or haecceity, everything becomes equivalent. If “this is a cat” is the usual understanding, then the photographic understanding is “a cat (proper noun) is this,” and in terms of the “this” in statements like “a vagabond is this” and “a bird is this,” the vagabond and the bird are linked by an equal sign. The result is a world in which human distinctions evaporate and in which “this” alone is endlessly repeated as pure difference, or in other words a world of madness.

I can think of no other photographer working today who takes photographs as pure as those of Takuma Nakahira. Harking back to the “origins” of photography, in essence, relying solely on the haecceity and equivalence of proper nouns, his work is enough to put to shame the legions of photographers who attach knowing hindsights (captions, etc) to their photographs. This style began with 1975’s “Amami Oshima” and 1976’s “Tokara Islets,” continued with 1978’s “Okinawa,” and after coming to a conclusion of sorts with “Shashin Genten 1981,” has continued, albeit in an increasingly rigorous form, to the present with A New Gaze (1983), Adieu a X (1989) and Hysteric Six Nakahira Takuma (2002).

What do I mean by “increasingly rigorous”? Comparing the three publications above, which are all available as separate photobooks, what one notices immediately is that the horizontal orientation that was still dominant in A New Gaze largely loses its place to vertical orientation in Adieu a X and is entirely absent from Hysteric Six Nakahira Takuma, with Nakahira focusing exclusively on vertical orientation ever since. Furthermore, comparing the motifs from the early 1980s to those of the 2000s, one can see that these, too, have been narrowed down considerably. As the horizontal orientation disappeared, so too did scenes with horizons and skylines, groups of ordinary people and children looking directly into the camera. Today these motifs are even more limited. Sleeping people, people with downcast eyes, people seen from behind. Cats, birds and other animals. Running water, landscapes and solo shots of things. Vegetation (filling the entire frame). Characters and signboards. Frontal views of objects (stone-carved guardian dogs, etc). In extremely rare cases (as far as I am aware, one black-and-white photo and two color photos to date), frontal shots of people on their own. And finally, a method was established whereby two vertical photographs of these carefully selected subjects were laid out or displayed on walls in pairs either without black borders or at full bleed.

If one looks at the motifs, it should probably be clear “Nakahira-esque” subjects are for the most part subjects that “don’t look back”; his motifs are absorptive. As well, he looks not for horizontal orientation in the form of compositions that extend horizontally to take in whatever subjects happen to leap out, but for vertical orientation in the form of compositions with vertical depth that enable the viewer to study and become absorbed in a particular subject. He also eliminates horizontal and horizon lines that automatically create a distance between the viewer and the subject. Other things to note are the compositions in which the viewer is peeking from the shadow at a subject in the distance; close-up solo shots; tactile textures such as thatch roofing and vegetation; rich, heavy tones; and conspicuously strong contrast. Looking at these, one can see that Nakahira is trying to bring the subject closer, make it stand out, and allow the viewer to become absorbed in it; trying to create a sense of depth that is different from spatial depth. Together with the frameless page composition and display methods, these all have the effect of encouraging absorption, and the rigorousness is actually something that has arisen as a result of these methods.

Left: “Moriyama kashiboto” (Moriyama rental boats, 2004).

Right: “Toshoji” (Tosho temple, 2009).

But what about the “characters” that appear alongside the aforementioned motifs? I doubt that anyone would be absorbed in “Moriyama kashiboto” (Moriyama rental boats) or “Toshoji” (Tosho temple). But what these two actually signify are “(Daido) Moriyama kashiboto” and “To (matsu) Sho (mei) ji.” In other words, the series of photographs of characters are photographs of things that have the same name as something else but whose realities are different, just as the reality associated with the name “Takuma Nakahira” is different before and after his memory loss. Furthermore, there are photographs with characters such “Hokkaido ramen” and “Shikoku Sanuki udon” – both taken not in their namesake cities but in Yokohama – of a type one could refer to as “characters in odd locations” in that they prompt us to ask, “What are these characters doing in a place like this?” but also in that here, too, the referential function of the proper nouns in question fails, they also relate to memory loss. As with the other subjects, the style of the character series is absorptive. In other words, the significance of the absorption in Nakahira’s photographs lies in its filling of the names that have become empty due to his memory loss. “My photography is an absolute necessity for me, having forgotten everything.” (epigraph, A New Gaze).

Left: “Shikoku Sanuki udon” (2005).

Right: “Hokkaido ramen” (2008).

To lose one’s memory is to lose the existence that once filled one’s name. In Nakahira’s case, the identity “I am Takuma Nakahira” has disappeared, and he is informed that the name “Takuma Nakahira,” of which he has no recollection, represents who he is. In order to live as the person with the name “Takuma Nakahira,” he must everyday fill that empty name. Since the knowledge that “I photograph” was completely forgotten along with the rest of his memory, all that remained was the knowledge that “It photographs.” Just as light from the outside world enters and fills the camera, giving rise to a single photograph, the world is absorbed into and fills the empty name “Takuma Nakahira,” restoring the owner’s lost existence. Not “I am Takuma Nakahira,” but “Takuma Nakahira is this.” Not an identifying photograph such as “This is a cat,” but a photograph of “this.” These daily photographs of “this” fill these days, this self, with this brilliant life. Nakahira’s photographs are the daily repetition of the absorption of the form “It photographs me.”

Left to right: Images of “a single eye” (2007), (2009), (2007).

Having awakened to this form, the photographer was able to maintain a critical distance from his own photographs by combining two photographs. The presentation of two photographs together places the viewer in the mode of automatically comparing the two, and so has the theatrical effect of interrupting absorption. As far as I can tell from looking at Nakahira’s photobooks and exhibition catalogs, the thing he was concerned with when combining the two photographs that make up each pair was the direction of each subject’s gaze (including not only the gaze of humans, but the gaze of birds, animals, stone-carved guardians and other objects). Most pairs are made up of “a thing without a gaze” and “a thing with a gaze.” Very few are made up of two things that both have gazes, while none feature people. In other words, by combining something that has a gaze (something waiting to be filled, ie, me) and something defenseless in the face of this gaze (something that fills an empty name, ie, it) these pairs of photographs demonstrated the very absorption implied by “It photographs me.”

Left to right: Photographs with “landscape falling off the edge of the frame” (2004), (2005), (2008).

Nakahira’s latest solo exhibitions at BLD Gallery and ShugoArts consisted of photographs taken between 2002 and 2010, and the biggest change over this period is the disappearance of the presentation method of showing photographs in pairs. As a result, the absorptive mode of Nakahira’s work has taken over, and the craziness of the photographs is even more exposed. With this style as the constant and two compulsive images of “a tactile surface layer” and “a single eye (a shot of a single subject captured center frame, open to interpretation as a metaphor for the ‘camera’s eye’)” as the variable (on this occasion), the sensibility of Takuma Nakahira the individual is doing nothing more than relating to the photograph. As if the artist himself is on the verge of being sporadically swallowed up by pure photographs (the equivalence of “this”) that have lost all sense of distance and become more and more intense. Only the “name” series is tenuously connected to the artist’s biographical life, while the small number of “photographs with landscape falling off the edge of the frame (to the extent that the landscape in the background that is visible beside the central ‘this’ is also captured, these are photographs not of ‘this’ but of ‘this also’)” narrowly escape the crazy power of Nakahira’s photographs. These solo shows were a terrifying tug of war.

Takuma Nakahira’s “Documentary” was on display at ShugoArts, Tokyo, from January 8 to February 5, and at BLD Gallery, Tokyo from January 8 to February 27.

Archive

Critical Fieldwork: Observations on Contemporary Art in Japan 1-6