For ‘Shomei Tomatsu: Hues and Textures of Nagasaki’

Part 2: 11:02 Nagasaki

If “Japan as it really exists” is absent, where is the reality, the “decisive moment,” of post-war “Japan”? In 1961, 16 years after the moment the atomic bomb exploded with a “flash” over Nagasaki,(1) Tomatsu Shomei encounters the city. For the front cover of 11:02 Nagasaki, his first photobook, published five years after the profound shock of this encounter, Tomei chose a photograph of a round pocket watch stopped at 11:02 placed in the center of a piece of glossy white fabric to resemble the Rising-Sun flag, while for the back cover he chose a photograph of a Rising-Sun flag stirring on the surface of some water. The place of Japan’s “decisive moment” seems clear. However, the text the photographer himself provided for the afterword concludes with the following words:

“As a sign that they are human, humans must drive their will into the passage of time like a stake and recover their fading memories for the entire amount of time that has passed. The terror that Hiroshima and Nagasaki experienced that August, and the anger of the survivors who suffer the cruelty of the stigma of illnesses caused by atomic-bomb radiation, must not be buried among the details of history.”(2)

11:02 Nagasaki is a book of rage and indignation. It is a documentary about the survivors of Nagasaki 16 years after the end of the war, but at the same time this rage and indignation is also directed at the very actions of taking and viewing photographs, or in other words at the system of modernist photography in the form of the “ethic of presenting things as they are.” To expose things “as they are” is to be dependent on the gaze of the exploiter who determines how these things are and to usurp the moment with one’s gaze, and even if the results stir the emotions they still bear the arrogance of those who discriminate. While Ken Domon’s photographs of Hiroshima have a verisimilitude that leaves no room for hope, they still fall within the bounds of modern “realist photography” and therefore reassure people. In contrast to this, Tomatu’s photographs of Nagasaki are infused with a suffocating oppressiveness on account of this dualism.

A-bomb survivors are people who had their “as they are” ripped from them on account of the moment of a “flash” that is absolutely external to photography. They are people for whom, on account of that moment, the rest of their lives changed, who must live through continuous suffering for decades, for generations, after the war, and who in addition to normal time live another layer of time that began that “11:02.” Moreover, government compensation and aid failed to reach the actual survivors, and even 16 years after the event the majority of survivors were still struggling amidst poverty. Their endless suffering can only be found in passing time. Surely photographs, which can only capture a single moment, cannot capture the suffering of passing time. If the moment of the “flash” gave rise to continuous suffering, how can the moment of a photograph cause this suffering to endure within the hearts of viewers?

Tomatsu used two methods to achieve this. First, he broke down the decisive moment into the passage of multilayered time. Herein lie the roots of the Hues and Textures of Nagasaki exhibition. 11:02 Nagasaki is a photobook in which the history of Nagasaki, photographs from the past and present, the poignant words of the survivors, and documentary photographs of their miserable reality are carefully edited and incorporated into the finished publication. The overall framework consists of four times unfolding in parallel: the time that stood still at 11:02 on August 9, 1945; the additional layer of time that began for the survivors on 11:02; natural time that passes irrespective of human activity; and the time of post-war Japan. The first is represented by photographs of the devastation, including clocks, beer bottles, helmets, and other artefacts from ground zero as well as photographs of statues of angels and so on. The second is represented by photographs showing the present for the survivors. The third is represented by photographs of plants and nature. The fourth is represented by photographs showing Nagasaki in 1961, including U.S. military bases, U.S. military personnel, and festivals. Furthermore, each of these photographs is imbued with all of the aesthetics of Tomatsu’s straight photography. Careful consideration has been given to all the factors discussed previously, such as the motifs, angles, backlighting, frontlighting, contrast, space, and the directions in which the subjects are looking, and practically every photograph is extremely dramatic and aesthetic.

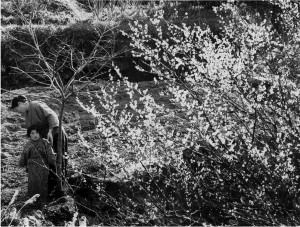

Let’s look at the photo of a mother and child next to a Japanese plum tree in full bloom that appears as a double-page spread more or less in the middle of the photobook. At the far left of the photograph, the mother directs her downward gaze outside the frame. Judging from the direction of her gaze, we know that her innermost thoughts are represented by the large space in the photograph. This space is filled with Japanese plum blossoms, which traditionally symbolize remembrance (“When the east wind blows, let it send your fragrance, oh plum blossoms”(3)), that take up most of the photograph and represent the emotions that fill her heart. Here, as well as expressing natural time, the plum blossoms are almost too beautiful, contrasting with the anguish and harsh reality of the mother. The child, who looks directly at the camera, is one-eyed (like a camera!). It is precisely because this little child’s eye is a single-lens reflex camera capturing the world as it is(4) and at the same time looking directly at the camera that the viewer is awakened to that part of themselves that is simply looking on, that is nothing more than an arrogant exploiter = a photographer, and that simplistic sentimentality and sympathy are avoided. One could say that this photograph is perfect. However, in the presence of the utterly austere reality of the survivors of the atomic bombing, all of this drama and beauty is expressed as “an embarrassment” alongside the “anger” at oneself for being unable to do anything except photograph such a reality. In the presence of a reality that “must not be beautiful,” the beauty of photography shatters into pieces, and the suffering and catharsis of this expresses the ongoing suffering of the A-bomb survivors. Tomatsu’s photography, which was ineffective when confronted with the absence of “things as they are,” responded to the suffering of people who had been robbed of “things as they are” by using all the photographic skills at its disposal to express this, or in other words by self-destructing. 11:02 Nagasaki is constructed in a way that is unavoidably emotive. Yet people are moved by being emotionally moved. Tears and so on are expressions of this level of emotion. And it is to “just this level” that Tomatsu has committed all of his talents. We are touched by such sincerity in a photographer. (To be continued)

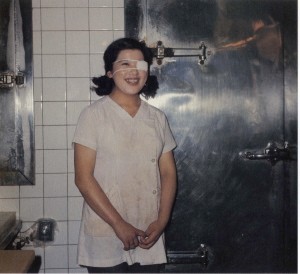

Ms Shizuka Uragawa (1975)

Ms Shizuka Uragawa (1975) Shinchimachi, Nagasaki, 1999

Shinchimachi, Nagasaki, 1999“Shomei Tomatsu: Hues and Textures of Nagasaki” was on display at the Nagasaki Prefectural Art Museum, from October 3 to November 29, 2009.

1. Shomei Tomatsu (editor), Nagasaki Mandara Nagasaki Shimbun Shinsho 016, 2005.

2. Shomei Tomatsu, 11:02 Nagasaki, Shaken, 1968.

3. Poem by Sugawara no Michizane (845-903).

4. Ms Shizuka Uragawa has a special status among the subjects of Tomatsu Shomei’s “Nagasaki” not only because of their personal relationship. She also appears in the Hues and Textures of Nagasaki exhibition, as does the one-eyed motif.