For ‘Shomei Tomatsu: Hues and Textures of Nagasaki’

Part 3: Darkness and Colors

Between the “ethic of presenting things as they are” and the artificial space-time of “occupation,” the black and white photographs that serve as an expression of the contradictions and inconsistencies between them, the self-disintegration of this form of expression in 11:02 Nagasaki and the exhibition “Shomei Tomatsu: Hues and Textures of Nagasaki” lies Okinawa – The Pencil of the Sun (1969-73), the termination of the state of ‘occupation’ with the return of Okinawa in 1972, and Sparkling Winds: Okinawa (1977-78) – which triggered Tomatsu’s shift to color photography.

There’s an extremely serious question in the form of for whose sake one takes photographs. In my case, this can be restated as for whose sake I go to Okinawa. […] I think in terms of reportage that serves neither the national interests nor my own personal interests. Photographs for the sake of the subjects. I go to Okinawa for the sake of Okinawa. If this reportage for the sake of the subjects is a success, then my hypothesis that “reportage is valid” has been verified. (1972)(1)

If I were to express it without fear of misunderstanding, I would say that I didn’t come to Okinawa but I returned to Japan, and that I don’t return to Tokyo but I go to the USA. (1975)(2)

Okinawa is one of the regions I’ve photographed continually over the past 10 years, but if you asked me what I’ve seen as a result of my involvement with Okinawa, it’s Japan itself. (1979)(3)

Perhaps it’s best described as a wonderful brightness. When you stand there you experience a feeling of pleasure as if a pure wind is blowing right through your body. (1979)(4)

A state of chaos in which nothing is differentiated. This undifferentiated state, or what you might call the totality of Okinawan culture, is something in which I’m extremely interested. (1979)(5)

Reportage = documentary, Japan itself, transparency, undifferentiated chaos – in Okinawa, Tomatsu found “things as they are” in a way that was surprisingly simple.(6) All the photographic skills that had been rendered ineffective under the occupation regained their substance, and the beauty of Tomatu’s photography came into its own boldly and vigorously. The “occupation” ended in the literal sense at the same time as this restoration of “things as they are,” and as if as a matter of course Tomatsu began to make the shift from black and white photography as a means of expressing contradictions and inconsistencies to color photography. Tomatsu’s color photography was introduced as a means of expressing the restored “things as they are.” Previously, the discourse of modernist photography, of surrealistic documentary photography, gave rise to inconsistencies in Tomatsu’s photography on account of the contradiction between “things as they are” and the occupation. Today, because he has rediscovered “Japan as it is” in the genuine, ancient layers of Japanese culture that extend from Okinawa to Southeast Asia via the kaijo no michi, or “ocean road” (Kunio Yanagita), Tomatsu is at last able to take modernist photographs – provided they are color photographs – that are free of inconsistencies.(7) It goes without saying that The Pencil of the Sun references one of the works that constitute the very origins of photography, namely Talbot’s The Pencil of Nature. In other words, it took on the meaning of a fresh starting point.

However, in the final analysis, this “as it is,” in other words this “ocean road,” is a supposition. Tomatsu’s photography found a world of brightness and colors amidst a kind of sense of liberation stemming from the fact that the photographs are wonderfully skillful and beautiful, but this is a sense of liberation supported by a fiction, and the “wonderful brightness” is a substitute that cannot possibly be compared with the ‘real’ of the actual yonder. The dualism of the restored “as it is” and “pictorialism” clearly became unbalanced in the favor of pictorialism due to the weakness of the former and Shomei Tomatsu’s innate pictorial flair. Indications of this unbalance were already apparent in the square 6×6 format of Sparkling Winds: Okinawa, and one could say that the Sakura series (1981-83), which traced the “ancient layers of things as they are” in reverse to the mainland, is the extremity of this. “On Okinawa, the thing that was restored inside of me was the pure beauty of cherry blossoms, their pure appearance as flora unsullied by ideology. I felt the urge to photograph them, which led to a cherry blossom pilgrimage in which I followed the cherry-blossom front as it marched up the country.”(8) How far we are from “Nagasaki.”

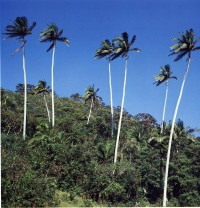

Hoshidate, Iriomote-jima (1978) from Sparkling Winds: Okinawa.

Hoshidate, Iriomote-jima (1978) from Sparkling Winds: Okinawa.The dispersed composition is almost identical to that of 25 years before [see Sit-down (Uchinada, Ishikawa prefecture) (1953)].

And yet, at the very same time, Tomatsu begins to photograph Nagasaki in color.(9) Naturally, the pictorialism with which he expresses the restored “as it is” does not work in Nagasaki. For the next 30 years Tomatsu’s color photography underwent a transformation that brought it to its current level.

This latest exhibition borrows both latently and visibly many motifs from 11:02 Nagasaki. In that photobook, the decisive moment was broken down into the passage of multilayered time and brilliant pictorial techniques nullified by the grave reality of the subjects. Here, the transformation of color follows the same process. In order for them to function as expressions of the current reality of a city that was robbed of its “as it is” in the atomic bombing, blue, red, green, and all the other colors have been broken down into “hues and textures.” As a result, rather than being peculiar to a particular subject, the colors permeate various other subjects through their textures. A single photograph becomes open to multiple collections of photographs – collections of photographs that exist as mutual vibrations of multilayered time – through its textures.(10) Simultaneously, the same function is bestowed on pictorial techniques, and on composition in particular. A single photograph resonates with another photograph through its similar composition.

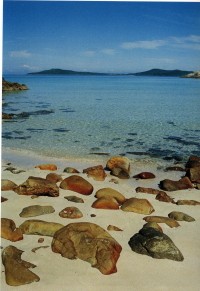

Miiraku-cho, Goto-shi, 2001

Miiraku-cho, Goto-shi, 2001 Urakami Cathedral, destroyed by the bomb blast, 1961

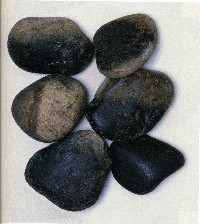

Urakami Cathedral, destroyed by the bomb blast, 1961 Rounded stones from a shrine showing evidence of heat rays, 1985

Rounded stones from a shrine showing evidence of heat rays, 1985

But just what are these mutual vibrations, resonations, and so on? In recent years Tomatsu’s photographs have been dominated by incredibly deep contrast, a mode of visual fixation, and absorptive motifs. The bright colors almost always have a background permeated with the blackest darkness, and somewhere in the photographs there is almost always a gaping deep black hole. From the photographs in which relics from the atomic bombing are digitally montaged with the actual scenery, the meaning of this darkness is clear.

Souls torn apart and scattered

Cherish our trifling existence

Dreaming of incomplete lives

(Sumako Fukuda, “The Atomic Field”)(11)

The colors as textures backed by darkness represent our trifling lives backed by the incomplete lives of the victims and survivors of the atomic bombing and Tomatsu’s love for Nagasaki.

“Shomei Tomatsu: Hues and Textures of Nagasaki” was on display at the Nagasaki Prefectural Art Museum, from October 3 to November 29, 2009.

1. Showa shashin zenshigoto 15: Tomatsu Shomei (Anthology of the Photography of the Showa Period, vol. 5: Shomei Tomatsu). Asahi Shimbunsha, 1984, p118. The words “for the sake of the subjects” and “for the sake of Okinawa” are emphasized in the original text.

2. Ibid, p116

.

3. Ibid, inside front cover.

4. Ibid, p108.

5.Ibid, p140.

6. So simple that he was able to express what he was completely incapable of putting into words in front of the survivors of the Nagasaki atomic bombing (“Photographs for the sake of A-bomb survivors”…).

7. This phenomenon whereby a return to the essence of photography is linked to color photography parallels the experience of one of Tomatsu’s contemporaries, Takuma Nakahira. Not only that, but many of the works in the exhibition Hues and Textures of Nagasaki are strongly reminiscent of Nakahira’s recent work. This parallelity is something I want to explore in another article.

8. Ibid, p20.

9. The present exhibition contains 11 works from 1975. It is difficult to imagine that Tomatsu took only 11 photographs in 1975 alone, from which one can surmise the extent to which color photography did not suit the subject of Nagasaki.

10. See Ryuta Imafuku, “Nagasaki kara, toki no gunto e” (From Nagasaki to the Archipelagos of Time) (on page 8 of the catalog for this exhibition) or Minoru Shimizu, “Shashinka no futatsu no kage – Tokatsu Shomei no henyo” (Two Shadows of a Photographer – The Metamorphosis of Shomei Tomatsu) in Shiro to kuro de (In Black and White), Gendai Shichosha, 2004, p183).

11. From Shomei Tomatsu, “Genso yubinkyoku, Fukuda Sumako-sama” (Fantastic post office, Sumako Fukuda-sama), Nagasaki Mandara, Nagasaki Shimbunsha, 2005, p63.