Imagining a Future for Life and Love

2009.11.28 – 2010.2.28

Mori Art Museum (Tokyo)

http://www.mori.art.museum

by Hashimoto Kazumichi (Researcher, Studies of Culture and Representation)

Photo Watanabe Osamu, courtesy Mori Art Museum

Contrary to what its subtitle suggests, Medicine and Art seems to overflow with representations of death. Certainly that’s the impression one would gain from a fleeting perusal of this show dominated by medical history materials from London’s Wellcome Collection and including three anatomical drawings by Leonardo da Vinci – two on display in Japan for the first time – plus a selection of contemporary art works. I doubt anyone could discern the slightest whiff of life in Renaissance-period sketches depicting bodies with skin flayed and innards on display, even if they do include heavily pregnant women. Contributions by the contemporary art contingent meanwhile include footage of Alvin Zafra’s performance of a crude funeral rite, in which the artist scrapes a human skull over sandpaper; and Walter Schels’ juxtaposing of subjects’ portraits immediately before and after death. Even the last section, titled ‘Toward Eternal Life and Love, in offering a glimpse of a glowing green genetically engineered bunny (Eduardo Kac) fills the viewer with a sense of unease, in this case about a future shaped by biotechnology.

Alvin Zafra Argument from Nowhere 2000

Courtesy Osage Gallery

Walter Schels Life Before Death-Elmira Sang Bastian

14th January 2004 / 23rd March 2004

Courtesy the artist

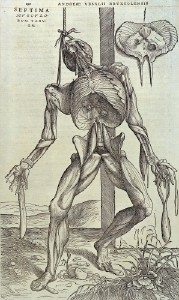

Still, it would be wrong to dismiss the offerings on display here as being relentlessly focused on death. For example, why do the bodies in anatomical texts since the Renaissance – a typical example being in the writings of Andreas Vesalius – stand there as skeletons as if posing, or peel back their own skin to reveal their viscera to us? Quite simply, because they are ‘alive’. The idea that the truth concerning life did not reside in the Christian soul, but could be found by exploring the body, was what made the medicine of this period so new. Dead bodies were used in these explorations for the simple reason that it was not possible to cut open live ones. Thus the bodies in anatomical diagrams successfully show the impossible, if only on paper.

Things once supposed to represent ‘life’ now remind us of death, in the end perhaps because both life and death are no more than abstract concepts, altering over time. That which is born, and dies, is merely the tangible, ie non-abstract body of the individual. George Washington’s false teeth, an artificial arm for a 16-year-old girl, a prosthetic leg for a soldier made from aircraft parts, faintly bloodshot glass eyes… How close does medicine, or art, really get to the bodies that these medical devices conjure up so vividly?

Andreas Vesalius: Skeletal Figure Hunging from the Rope in Humani Corporis Fabrica

1555/ Basileae, Switzerland, Wellcome Library