Critical Fieldwork 28

Neither decolorized nor faded – The latest color photographs by Daido Moriyama (Part 3)

As is well known, Stieglitz “seceded” from pictorial photography that did no more than mimic symbolist or impressionist painting to pursue “the idea photography.” (1) The changes in his journal Camera Work (1903-1917) paralleled the solidification of Stieglitz’s views on photography and the establishment of modernist photography. For the first few years this journal was no more than a means for Stieglitz to publish highly original pictorial photographs, but with the introduction in 1907 of color aided by Autochrome, photography began to draw closer to Modernist painting. To the surprise of many, in his pursuit of the idea of photography, Stieglitz turned his attention towards the paintings of artists like Picasso and Braque. At the time, the artwork of Picasso and Braque largely took the form of constructions and collage. In other words, one could say that the “idea photography” Stieglitz derived from Modernist painting was collage reinterpreted for photography. Unlike “composition,” in which various elements are combined within a given frame, collage is a process whereby new frames (layers) are created one after another by attaching pieces of paper and adding drawn lines. If the process whereby new frames were applied to objects was collage, Stieglitz reasoned, then the process whereby new frames were applied to the existing world was photography. In other words, the “idea photography” was framing. (2)

In fact, Stieglitz’s photographs from this period framed the subjects in combination with different things. This view of photography, which regarded it as the practice of collage in the form of framing, underlies not only the photographs reproduced in my previous column, but all of Stieglitz’s photographs up to and including his skyscraper photographs of the 1930s. It was in the 1910s that Stieglitz formulated this outlook. At the time, color was nothing more than superfluous decoration. He renounced pictorial photography (including even Cubist painting-style pictorialism, such as Coburn’s “Vortographs”) and abandoned color. Before long, having come to the realization that, even if various objects were not consciously arranged in front of the camera, framing itself was none other than collage, Stieglitz was able to view his own photographs from the past in a new light, which led him to the discovery of the “snapshot” as “a process of applying new frames to the existing world.” Combined with newly perfected printing techniques (platinum, palladium, gelatine silver), this led to the establishment of “straight photography.” The result was pure collage, produced using “chiaroscuro” (ie, light and shadow). (3)

Daido Moriyama – Record No. 19 (2011) © Daido Moriyama, Courtesy Office Daido.

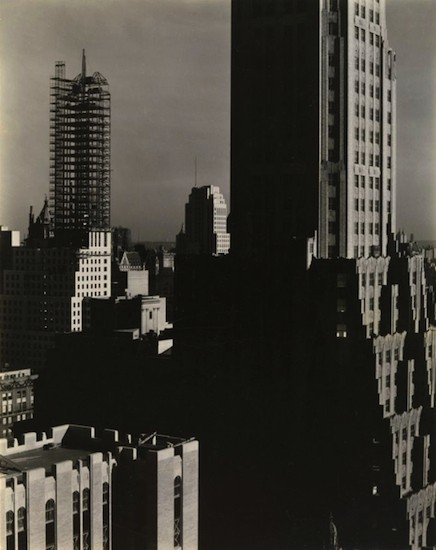

Daido Moriyama – Record No. 19 (2011) © Daido Moriyama, Courtesy Office Daido. Alfred Stieglitz – Looking Northwest from the Shelton (1932)

Alfred Stieglitz – Looking Northwest from the Shelton (1932) As I pointed out last time, the “collage-like composition” of Daido’s recent photography is a recreation of straight photography. There are two reasons why he is pursuing this now, and moreover in color. 1) The farewell to “light and shadow” accomplished by the “hysteric” works was half-hearted. This is because, even if they are regarded as extreme examples, the picture planes rhythmically collaged in high contrast using miscellaneous urban motifs ended up being contained within the straight photography category of “chiaroscuro” (ie, light and shadow). To put it another way, regardless of the subject and how he shot it, the result was always “art photography” in which the centrifugal force essential to “collage” was diminished by the centripetal force that historically accompanied black-and-white photography and therefore exhibited only half-heartedly. Which is why, 2) there is a need to pursue the exact opposite of Paul Strand’s notion that “there is nothing in common between color and photography.” And so, there is no difference in subject, style, and so on between Daido Moriyama’s color photography and his black-and-white photography. Color, however, is imbued with the ability to prevent a photograph turning into an “artwork” so that it remains just a “photograph.” Accordingly, the object of Daido’s color photography is not color itself. (4) Rather, it is a secularizer designed to counteract the centripetal force of black and white and ensure the photographs remain photographs. Due to the use of color, the centrifugal force of collage retains a secular, disharmonious “noisiness” without being absorbed comfortably in the black-and-white picture plane. In this way, Daido Moriyama’s color photography resists becoming a series of complete “single photographs,” and instead exposes to view as is our sober, versicolored everyday lives in which multiple memories and multiple scenes noisily echo and re-echo. “Farewell, modernist photography” (Farewell, Photography, 1972), “Farewell, light and shadow” (Lettre a St. Lou), and now “Farewell, hysteric” (Color). Daido Moriyama has finally arrived in a world of photographic multiplicity where memory and collage are like the two wheels of a cart, a world he has sought for many years during which he has bid farewell to the landing place of each in succession. How full of rich curiosity is our seemingly mundane everyday life.

Both: Daido Moriyama – Tokyo (2012) © Daido Moriyama, Courtesy Taka Ishii Gallery and Office Daido.

Both: Daido Moriyama – Tokyo (2012) © Daido Moriyama, Courtesy Taka Ishii Gallery and Office Daido.-

Alfred Stieglitz Photographs & Writings, National Gallery of Art, Washington, 1999.

- The famous “Equivalent” series (1923-34) is a true demonstration of this. This was a series of photographs that began by taking unobstructed views of the “sky” as their subject to emphasize the fact that artistry in photography is not reliant on the subject. The standard interpretation that deems this series the “equivalent” of mental images formed by the artist is nothing more than an explanation of the title rather than of the photographs themselves.

- The actual quote by Strand, Stieglitz’s favorite pupil, is as follows: “The photographer’s problem, therefore, is to see clearly the limitations and at the same time the potential qualities of his medium, for it is precisely here that honesty, no less than intensity of vision, is the prerequisite of a living expression. This means a real respect for the thing in front of him, expressed in terms of chiaroscuro through a range of almost infinite tonal values, which lie beyond the skill of the human hand. The fullest realization of this is accomplished without tricks of process or manipulation, but through use of straight photographic methods.” Paul Strand, “Photography,” first published in Seven Arts (1917); cited from Classic Essays on Photography, ed. Alan Trachtenberg, Leete’s Island Books, 1980, p.142.

- Why digital photography? On enquiring with the artist’s studio, I was told that no image processing, tone correction, or so on is carried out. I have no reason to doubt this, although given the kind of compact digital camera used by the artist (Ricoh GX200, Nikon Coolpix S9100, etc.) one would have thought more balanced color photographs would have been produced automatically, and I sense that while there has not been any processing or correction, in some of the works the contrast ratio, color saturation, and so on were not at the default settings. The latest digital cameras are programmed to reproduce automatically bright, beautiful, balanced color tones. This will likely not only lead to the standardization of color tones among many artists who belong to the digital camera generation, but also give rise to color effects that are non-essential and unnecessary from the standpoint of Daido’s color photography. In any event, because the main reason d’être of color is secularization, this does not change the fact that digital color, ie, color that is 100 percent guaranteed readymade (the result of some program setting regardless of the color tone and unachievable in “straight photography”) is the most suitable in the circumstances.