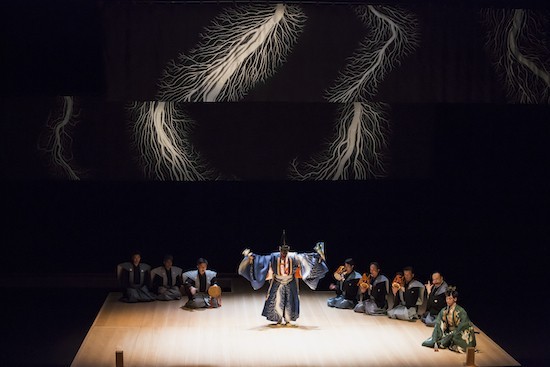

From ‘negative’ eternity to ‘positive’ eternity: Mansai Nomura and Hiroshi Sugimoto – SANBASO, divine dance Kami hisomi iki II (Part 1)

Scene from Mansai Nomura and Hiroshi Sugimoto’s SANBASO, divine dance Kami hisomi iki II. © Sugimoto Studio, courtesy of Odawara Art Foundation

In recent years it almost seems as if Hiroshi Sugimoto has lost interest in photography. It is possible to understand his work in architecture, interior design and furniture design based around the New Material Research Laboratory as an extension of his elaborate photographic installations, but how do his productions and reproductions of Japanese traditional performing arts – and in particular kyogen and bunraku – at the Odawara Art Foundation relate to his photography?

Modern photography has responded to the question, What is photography? with a single principle. According to this principle, photographs must capture as is the world as it is. “As is” means the world in its crude form unsullied by the aesthetics or values of the photographer or by images or language, a world in which existence prior to the separation of subject and object alone shines. “The ocean before it was named the ocean,” for example, or an everlasting world consisting of nothing but light and elements in which there are no “people.” And Hiroshi Sugimoto is one photographer who has upheld in his own unique way this modern principle of “eternity.”

The more my objective gaze directed at myself is finely honed, the more the undifferentiated, complete world begins to open my eyes. […] At the same time, my own profile gradually recedes from that which once highlighted it. The sounds I hear all turn into music and fade away, and existence itself begins to sparkle. (Hiroshi Sugimoto, 1977)

For me, the camera is a device for capturing as is the world as it is. […] To use a figure of speech, the world as it is is like a pure white screen, and your eyes are like a projector manifesting your own world upon this white screen… The camera, this “unsullied eye,” sees the world as it is. (Hiroshi Sugimoto, “The world as it is,” memo from June 1995)

However, the 1970s, when Sugimoto moved to the US and began producing photographs, was a time when the principles of modern photography began to break down in the face of the information capitalist society, which was beginning to expand globally. Faced with the imminent extinction of the “everlasting world,” many photographers asked once more the question, What is photography? Sugimoto, however, chose to believe, as the last modernist, as it were, in this now impossible eternity. Furthermore, he began looking for a means of expressing through photography the fact that this everlasting world could no longer be captured in photographs. Because the only thing photography could now do was not capture for posterity “the everlasting world as it is,” but capture the fact that it could no longer be captured. Hiroshi Sugimoto’s photographs have consistently from the very beginning expressed negatively – in the form of negatives – this impossible “eternity.”

Hiroshi Sugimoto – La Boîte en Bois (The Wooden Box) (2004). © Hiroshi Sugimoto, courtesy Gallery Koyanagi.

It is possible to formulate Sugimoto’s photography from this point to around 2004 (La Boîte en Bois (The Wooden Box) (Replica of Duchamp’s Large Glass)) as follows. The everlasting world as it is exists (the principle of modern photography). But this everlasting world has already ended, and can no longer be captured in photographs. Accordingly, all that photography can do is avoid betraying or sullying this world, which is to say, the photographer must vaporize, reduce to zero/empty, all unnecessary expression in their photographs. The details of this are explained elsewhere (1), but in short, the various series undertaken by Sugimoto from “Dioramas” through to “The Large Glass” are all none other than methods of keeping photography in a pure “zero” state. The everlasting world as it is has been lost from photography forever, and for this very reason it shines forever as something invisible to the naked eye. It is to avoid sullying this shine that Sugimoto invents his own “as is-ness” (plus) and draws our attention to this fakeness (minus), reducing photography to emptiness (zero, pitch black, glittering white light) and preserving eternity in a negative form. Coming as it does at the end of this sequence, “The Large Glass” constitutes a definite juncture in Sugimoto’s entire creative output as a basic model.

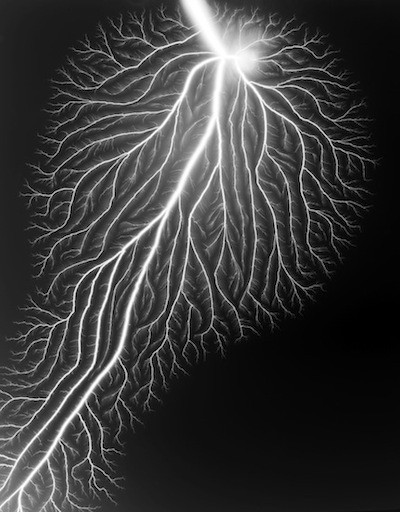

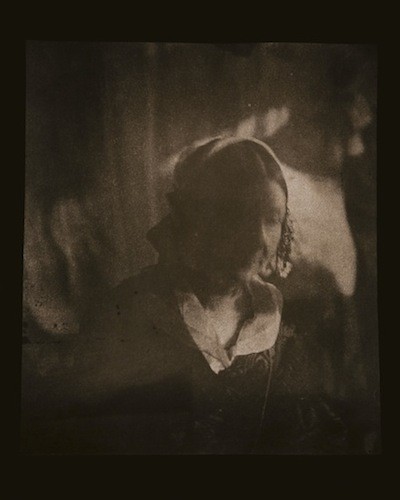

“The Large Glass” is usually regarded as an “allusion” to Duchamp’s work, but in concrete terms the method of “allusion” Sugimoto introduced at this point involves recreating the artwork of a predecessor using the negative-positive process. Almost as a matter of course, Sugimoto’s next step was to apply this method to the inventor of the negative-positive method, William Henry Fox Talbot. This gave rise to the “Photogenic Drawing” series, made using Talbot’s earliest negatives, which some have compared to “pure photography,” and to the “Lightning Fields” series, made using the phenomenon of electrical discharge as a “natural pencil” to “write” on photographic dry plates. Unlike traditional photographic expression using negatives, the works in these series exhibit qualities consistent with the recreation as developed positives of the “eternity” that existed at “the beginning.” This is the eternity of natural law, making manifest as a time machine the distant past as it was, just as a lightning bolt billions of years ago and a lightning bolt today are the result of the same natural law. In the same way, photography is seen as an everlasting physical phenomenon, or photochemical phenomenon. Photography becomes a time machine, sending Sugimoto back to the beginning of these phenomena, and so it is that in the “Talbot” series “pure photography” is recreated by means of allusion and in the “Lightning Fields” series eternal natural law in the form of lightning produces a photochemical phenomenon, recalling the pure “origins of photography.” It was these very images of “lightning fields” that were used as important motifs in this Sanbaso performance. (To be continued)

Hiroshi Sugimoto – Lightning Fields 019 (2007-08). © Hiroshi Sugimoto, courtesy Gallery Koyanagi.

Hiroshi Sugimoto – Photogenic Drawing 015, Believed to be Mlle. Amélina Petit, Talbot Family Governess, circa 1840–1841 (2008). © Hiroshi Sugimoto, courtesy Gallery Koyanagi.

Mansai Nomura and Hiroshi Sugimoto – SANBASO, divine dance Kami hisomi iki II was performed April 26 at Sakura Hall, Shibuya Cultural Center Owada following its New York tour as SANBASO, divine dance Mansai Nomura + Hiroshi Sugimoto on March 28 and 29 at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum.

http://www.odawara-af.com/jp/information/20130115post.html

-

Minoru Shimizu, “Fiction and Restoration of Eternity: On Hiroshi Sugimoto,” Pluramon, the singular-plural being, Gendai Shicho Shinsha Publishing, 2011. Originally published with English translation as “Fiction and Restoration of Eternity: Hiroshi Sugimoto’s Recent Photographs” in Hiroshi Sugimoto: Nature of Light (ex. cat.), Izu Photo Museum/Nohara, 2009.