Frames ≠ layers: The photography of Tamotsu Kido

Born in 1974 and a graduate of the oil painting course at Aichi Prefectural University of Fine Arts and Music, Tamotsu Kido is familiar to those in the know as a photographer. (1) Let us begin our discussion by considering “view,” an early series of elaborate, beautiful gelatin silver prints based on strict symmetry.

Tamotsu Kido – view#2 (2002)

Tamotsu Kido – view#2 (2002) Left: view#3 (2004). Right: view#10 (2008).

Left: view#3 (2004). Right: view#10 (2008).While reminiscent of the series of photographs of the parks of Sceaux taken by Eugène Atget towards the end of his life, the works that comprise “view” are far more abstract in nature, by which I mean they express exactly a single essential quality to which photography has been narrowed. Although Kido’s photographs do not resemble so-called street snaps or documentary photographs, it would be wrong to deem them “pictorial” on this basis. Kido’s photographs are photographs of the essence of photography, and if they do resemble “pictorial” photographs this is none other than because the essence of much of contemporary painting is photographic. (2)

This “essence” is layers. As mentioned in my discussion of Daido Moriyama (No. 28 in this series), in the early 20th century, Alfred Stieglitz “broke away” from the photography of the period and instead sought “the idea photography” in the collages of artists such as Picasso and Braque. Whereas collage is the process of applying new frames (layers) to existing objects, photography is the process of applying new frames to the existing world. Or in other words, “the idea photography” lies in framing. It was this realization that led Stieglitz, who was already familiar with the rich colors of Autochrome, to ditch color altogether. In a manner of speaking, the photographs in the “Equivalent” series, which were effected solely by framing the sky that stretches out above our heads, were zero-degree photography. In the sense that all material phenomena are “able to be captured in photographs,” clouds and cities and females as well as the self are all “equivalent.”

One of the essences of photography lies in framing, and framing involves reducing the world to a single four-cornered plane, or in other words creating layers. Framing = creating layers. The equal sign signifies that the layers appear as superposed four-cornered transparent planes (frames). In achieving this, Tamotsu Kido’s originality stems from the fact that he composes separately the framing (ie, the configuration of the rectangles) and the layering (ie, the appearance of the transparent planes). In other words, he frames his photographs in such a way that the layering occurs in a dimension different from the rectangle of the frame.

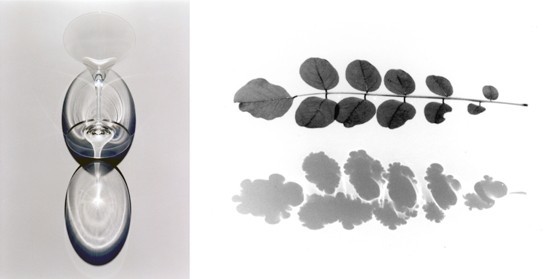

Left: glass#3 (1998). Right: leaf#4 (2001).

Left: glass#3 (1998). Right: leaf#4 (2001).This sensibility is already noticeable in Kido’s early series such as “glass” and “leaf.” In the former he directs light at a glass set on its side on white paper and photographs the result from directly above. In the photographs, both the projection plane formed by the shadows and the plane (at right angles to the surface of the white paper) called to mind by the base of the glass appear. In the latter he floats leaves on the surface of water and photographs them with light shining from above. Due to the fluctuation of the shadows, it is suggested that the leaves are floating on the water, or in other words the presence of the water surface is alluded to. “view” was created as an extension of these works, and represents their completed version. Because symmetry is a relationship of mirror images, it has the effect of causing a mirror surface to appear along the axis of symmetry. The scenes are framed in perfect symmetry, as a result of which mirror surfaces (ie, layers) that run at right angles to the picture plane appear along the axis of symmetry. The essence of photography does not rely on the subject, which is why Stieglitz photographed “the sky” and why Kido photographs a relation (ie, symmetry) that does not rely on a subject. “view” was Kido’s “Equivalent.”

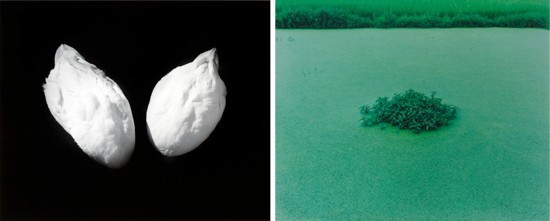

Since then, until the appearance of his new color works, Tamotsu Kido’s photographs have remained faithful to the fundamental principle of image segmentation by way of layers separate from the rectangle of the frame. At times a water surface slices through the subject (a);

Left: duck#3 (2010). Symmetry + breaking the water surface: two ducks thrust their heads into water. Right: green landscape (2012). The water surface covered in algae.

Left: duck#3 (2010). Symmetry + breaking the water surface: two ducks thrust their heads into water. Right: green landscape (2012). The water surface covered in algae.highlights created by sunlight filtering through foliage or shadows of trees cause the surface receiving the light or shadow to stand out (b);

Left: forest#2 (2010). Right: tree and shadow (II) (2010).

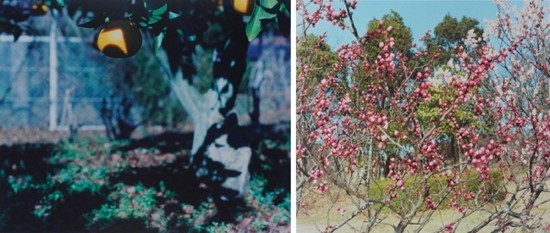

Left: forest#2 (2010). Right: tree and shadow (II) (2010).a focal plane set at around medium depth divides the scene into front and back (c);

Left: mandarin orange tree (2011). Right: plum blossoms (II) (2008).

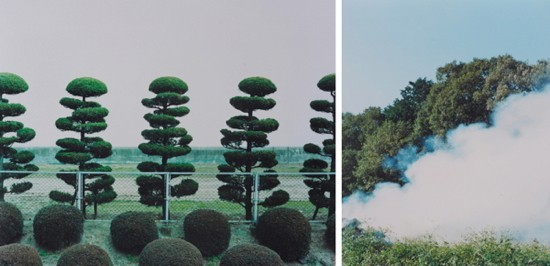

Left: mandarin orange tree (2011). Right: plum blossoms (II) (2008).or a subject resembling a layer such as a fence or wall or column of smoke serves as a frame or color surface blocking part of the scene (d).

Left: karimoku (2012). Right: smoke (2011).

Left: karimoku (2012). Right: smoke (2011).Looking at a photograph involves none other than looking at layers, but these layers are not the four-cornered photographs before one’s eyes. Behind this lies the fundamental concept of placing layers on a different dimension from the frame, a different dimension that arises as a result of the relations between the subjects, such as symmetry and the distribution of highlights. Because this fundamental concept functions similarly regardless of whether a photograph is black-and-white or color, and because in either case the artist does everything from developing the film to printing and dry mounting the photographs himself, one could say the two are part of a continuum. That being so, wherein lies the significance of Kido’s use of color?

First, the use of color, as a matter of course, yields relativity between colors. Color adds another, separate dimension to Kido’s work in the form of the correlation of layers. In other words – and this is something particularly conspicuous in the landscape works (d) in which color appears in clumps (the clumps of thicket) or planes (the blue galvanized sheet iron wall) – as well as constituting layers independent from the rectangle of the picture plane, these lumps and planes have a fixed color value with respect to the picture plane as a whole. Depending on their color, the layers that have appeared either float above the picture plane or are buried beneath it. As well, with respect to the patterns in (c) above, the color relationship between the objects in focus and their background naturally affects the vividness of the appearance of the focal plane.

Left: landscape with a metal drum (2012). Right: red flower and landscape (2011).

Left: landscape with a metal drum (2012). Right: red flower and landscape (2011).The second reason for the introduction of color should automatically become clear upon comparing black-and-white and color photographs in the same series. As was the case with Daido Moriyama’s color photography, color is a secularizer, restoring an element of the real world to photographs that have been sublimated into “artworks.” Kido’s color photographs are liberated from the suffocating tension of black-and-white photographs that have been reduced purely to the essence of the appearance of layers within a rectangle with no loss whatsoever of this essence, allowing them to breathe calmly as depictions of scenery on a particular day or at a particular time.

Left: forest#c3 (2011). Right : view#c1 (2008)

Left: forest#c3 (2011). Right : view#c1 (2008)Tamotsu Kido’s exhibition was on display at See Saw gallery + cafe, Nagoya, part 1 from July 10 to August 11, and part 2 from September 4 to October 6, 2012.

-

He debuted in 2002. In 2003, after happening to see an announcement card for a Tamotsu Kido exhibition, I visited Gallery NAF at the Kawaijuku Art Institute in Nagoya, as a result of which Kido’s name became engraved in my memory. However, partly because he is such an unprolific artist who works at his own pace, his next solo exhibition wasn’t until seven years later (in 2010 at Galerie Tokyo Humanité), and it was a further two years until his first solo exhibition of purely color photographs.

- For example, the seemingly colorful paintings of Gerhard Richter have, from the earliest photo-paintings to the latest strip paintings, consistently given expression to the contemporary painting system of “layers”regarded as a “dead readymade.” In fact right now there is a solo exhibition at the Marian Goodman Gallery in New York featuring a series of Richter’s strip paintings along with the sculpture 6 Standing Glass Panels, which both rely on the same structure. In the strip paintings, a single abstract painting is developed according to a process of mirroring (see Gerhard Richter Patterns: Divided-Mirrored-Repeated, Verlag der Buchhandlung Walther König, 2012), giving rise to a single mirror plane (ie, layer) with each mirroring, and so the strip painting resulting from repeating this 4096 times would in a sense be 4096 standing glass panels. Likewise, the photography of Ellsworth Kelly, a reference point of Kido’s, is an expression of the layers that appear in picture planes in the form of projection planes, light receiving surfaces and so on, and geometric configurations such as zigzag lines and triangles are not the issue.

Left: Ellsworth Kelly – Shadows on Stairs, Villa La Combe, Meschers (1950).

Right: Ellsworth Kelly – Hangar Doorway, St. Barts (1977).