Moving Photographs: Taiji Matsue’s ‘survey of time’ (Part II)

ANF 100465 (2010), Single channel HD digital video, 28 min 50 sec. All images: © Taiji Matsue, courtesy Taro Nasu.

At a time when, due to the virtual integration of digital video and digital cameras and advances in the resolution and processing capabilities of video, it has become more or less impossible (unless one is a professional in this area) to distinguish between video captures and digital photographs – in essence, the “decisive moment” has become an impossibility – Taiji Matsue’s first motion picture work emerges as one possibility for digital photography (as opposed to digital video). To be sure, these works make use of DVD media, but they are far closer to still images than moving images. In the near future, once LCD monitors, organic EL displays and the like have become so thin that paper-like displays are the norm, we may have to start calling them “moving photographs.” In the case of Matsue’s work, not only has the sound been removed, but over 90 percent of the screen area is taken up with a frozen photograph, with only the remainder (less than 10 percent), comprising details that one hardly notices, exhibiting movement akin to ciliary movement or rivulets. Somewhere within a frozen landscape a small hint of a movement flows and appears.

The results appear similar but are different from the type of work in which occasional events (the appearance of passersby, the blinking of subjects) are inserted into frozen long takes shot using fixed cameras, as seen in Beat Streuli’s images of passersby and Thomas Struth’s “Video Portraits” (1996-2003), for example. In Matsue’s work there is no suggestion of the steady passage of time as seen in Streuli’s work, some of which is reminiscent of background video of a street viewed from a café, and in compositional terms, as well, Streuli’s closing in on the subjects and Matsue’s sweeping views of scenes in the distance are completely different. If the theme of Streuli’s work is “photography = recording = assigning to the past,” “video = live = the present progressive,” then it is the substitution of “memory” and “direct manifestation,” and if we consider “movement = life,” “stillness = death,” then it is the flickering of life and death. Even if it connects with Matsue’s work on the level of the general problematic of moving image = live = life, still image = record = death, then this is still only a connection.

The biggest difference between the works of the two artists mentioned above and that of Matsue is that while the former bring together and substitute video and photography without questioning the identity of each of the media concerned (as in “video = moving image” and “photograph = still image”), in Matsue’s work, as mentioned at the outset, there is no distinction between the two and such problem formations as image = live = life and still image = record = death have themselves fallen by the wayside. This is probably the origin of the peculiar sensation triggered by his “moving photographs.” The distinction between still images and moving images disappears, offering a glimpse of the border between frozen time and flowing time that is neither ice nor water. If applying a tangent to a continuous timeline is the photograph as “decisive moment = point of contact,” then the temporality of digital photographs is akin to curves that are continuous but have no tangents. A fractal curve, for example, has intermediate dimensions (1.26 and so on) because the first dimension (line) and second dimension (plane) are continuous with the same density, and in a similar way, Matsue’s “moving photographs” represent an unknown form of photographic expression in search of intermediate dimensions based on the fact that photographs (still images = points of time) and video (moving images = timelines) are connected by digital technology.

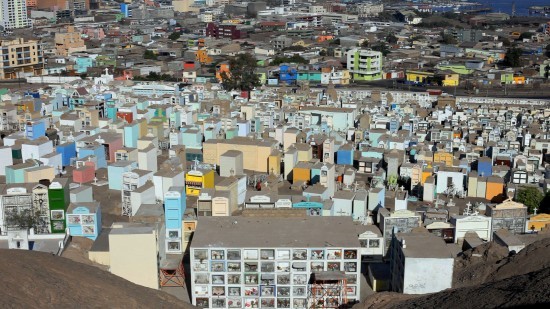

The work ANF100465 depicting what appears to be a colorful model of a town was in fact shot at a cemetery in Mexico. As one gazes intently at this “photograph” of a scene that has literally died, a workman unexpectedly wanders across it, and a while later three birds flutter across it casting shadows. One then notices cars rushing along a highway at the top right of the “photograph.” These are the only examples of movement, and because the rest of the “photograph” is completely still, these small movements leave a powerful impression on the viewer. Like people who have fallen sleep on commuter trains and awaken with a start the moment they begin to topple over, we experience a kind of awakening. Analog photography was a medium that cut off a particular reality at a point of singularity in time (ie, a point of contact, a decisive moment) and froze it as the eternal past. The viewer became absorbed in the eternal past captured in a photograph, as a result of which the past manifested itself in the here and now. Digital photography, however, completely nullifies this process of severance – freezing – manifestation. One could say that what Matsue’s photography is expressing is this nullification. The lack of a point of contact makes severance impossible, and the moment a photograph begins to freeze into an eternal past something in the frame moves, bringing it back into currently elapsing time. The present is handed over not to absorption but to awakening.

Above: ARI 100585 (2010), Single channel HD digital video, 29 min 40 sec. Below: ATACAMA 100435 (2010), Single channel HD digital video, 29 min 55 sec.

ARI100585 and ATACAMA100435, photographed in Chile, both depict an overwhelmingly barren landscape through which a long, narrow train passes just once, several cars approach from afar, and horses roam around a tiny pasture. It is a simple matter to observe the contrast between these landscapes full of death and barrenness and the lives of the people who appear to cling to them, but Matsue expresses this not as a contrast between “still images = death” and “moving images = life,” but as “moving photographs” in which life and death form a continuum, as it were, or as life transformed into a part of overwhelming death. Perhaps this is Matsue’s realism in response to these landscapes.

QUI 100520 (2010), Single channel HD digital video, 26 min.

In QUI100520, which features a massive opencast mine in Chile, one can see a different kind of problematics with regard to absorption and awakening. Footage of trucks ceaselessly ascending and descending with copper ore taken from the mine forms a loop. This footage is extremely absorptive, even dreamlike. Yet these trucks that look the size of peas are actually megaton trucks more than 5m high, and their slow movements that almost bewitch the viewer are not the result of slow motion but a fiction generated by the almost unimaginably massive scale of the trucks and the great distance from which they have been shot. The point of this “moving photograph” lies in the generation of this effect in which the passage of time appears to be delayed, an effect achieved by linking one of the characteristics of photography – its inability to portray on its own the size of subjects – to the playback speed of the video and shooting the massive subjects from an extremely great distance. This, too, is one expression of an intermediate dimension.

Taiji Matsue’s “survey of time” was on display at Taro Nasu, Tokyo, from October 23 to November 20, 2010.

Archive

Critical Fieldwork: Observations on Contemporary Art in Japan 1-6