Seiichi Furuya: The Disclosed Mémoires (Part I)

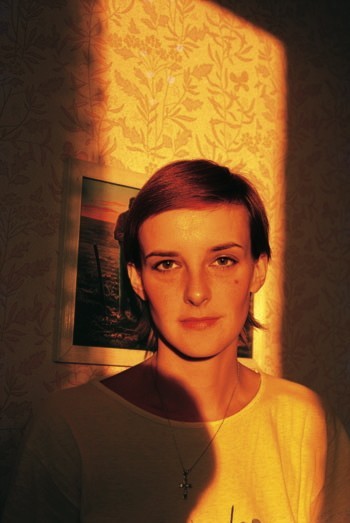

East Berlin, 1985.

East Berlin, 1985.Published intermittently since 1989, Seiichi Furuya’s series of photobooks entitled “Mémoires” was concluded this year with the appearance of volume five. Furuya’s 25-year “journey” began in the fall of 1985 with a specific event as its starting point. That event inevitably led him to the most essential “point” of modern photography and changed completely the meaning of his photography until then and thereafter. Consequently, while this series began as a unique documentary aimed at elucidating the truth of the event, at the same time it developed into nothing less than a journey aimed at inquiring into the significance of photography itself. The five volumes of “Mémoires” represent both individual paths on this journey as well as the documentation of changes in Furuya’s attitude towards his very reading of photography.

Regarding the essential “point” of modern photography, in an interview Jacques Derrida commented:

[…] however artful the photographer may be, whatever his or her intervention or style, there is a point where the photographic act is not an artistic act, a point where it passively records, and this poignant passivity would be the chance of this relation with death; it captures a reality that is there, that will have been there, in an undecomposable now. […] This would be the beauty or the sublimity of photography but also its fundamentally nonartistic quality: suddenly, one would be given over to an experience that fundamentally cannot be mastered, to what has taken place only once. So one would be passive and exposed; the gaze itself would be exposed to the exposed thing, in the time without thickness of a null duration, in an exposure time reduced to the instantaneous point of a snapshot. (1)

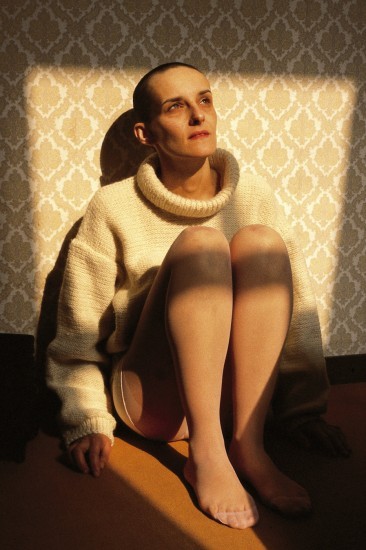

Venice, 1985.

Venice, 1985.For Furuya, the “point” where he was “suddenly…given over” was some time after 12:30pm on October 7, 1985, at Falkenberger Chaussee 13, East Berlin. On this day his wife, Christine, who he met in February 1978 and married in May that same year, and who had been receiving intermittent treatment for depression since around 1983, suddenly threw herself from the ninth floor of their apartment building, ending her own life. On account of this point of singularity – the suicide of a loved one – each and every photograph Furuya had taken up to that point became a portent of this event, and each and every photograph he took after became its trace.

The photograph as a portent of a “piercing” point (punctum), the photograph as the revival of the piercing experience of “here and now.” As Derrida points out, this is the essential framework of modern photography. The point of singularity connects the past and the present without regard for temporal order. In Furuya’s case, the name Christine became attached to this point. The first volume in the series, Mémoires 1978-1988, addressed the absolute truth of Christine’s suicide and included photographs taken before and after that event. As critic Christine Frisinghelli reveals, these photographs were part of five series originally shot in a totally different context: “Staatsgrenze” (1980-83), “AMS” (1980), “Soweit das Auge reicht” (1982-84), “Limes – Bilder der Schutzmauer aus Berlin-Ost, Hauptstadt der DDR” (1985-88) and “Stadtbilder Berlin-Ost” (1985-87). As is clear from a memo Furuya himself wrote in 1980, even the reoccurring portrait photographs of Christine were part of an effort “to document the life of a single individual” and “discover oneself by looking at her, photographing her and studying these photographs.” (2) Various groups of photographs were removed from the context in which they were originally placed and edited with no regard for temporal order. “Aus den Fugen” (out of joint), the title of Furuya’s pair of solo exhibitions at the Vangi Sculpture Garden Museum in 2007 and 2010, is a reference to these circumstances. But a common thread running through all Furuya’s editing is the will to demarcate as clearly as possible that one point of singularity. In this sense, and in this sense only, the artist is extremely centripetal, with the groups of photographs that had initially been dispersed being firmly tied together. In other words, this photobook is an attempt to singularize or simplify photography in the direction of a single “point” representing the essence of photography. “Christine” was the singularizing element of the photographs.

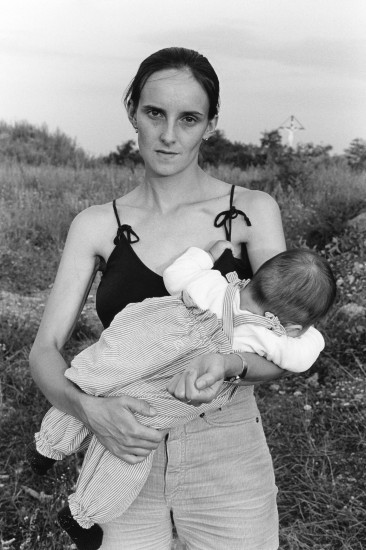

Graz, 1983.

Graz, 1983.Incidentally, in the interview referred to above, Derrida prefaces the quoted section by attempting to open up this “singular” nature of photography to plurality:

But if the “one single time,” if the single, first and last time of the shot already occupies a heterogeneous time, this supposes a differing/deferring and differentiated duration: in a split second the light can change, and we’re dealing with a divisionality of the first time. Reference is complex; it is no longer simple, and in that time subevents can occur, differentiations, micrological modifications giving rise to possible compositions, dissociations, and recompositions, to “effects” […] that definitively break with presumed phenomenological naturalism that would see in photographic technology the miracle of a technology that effaces itself in order to give us a natural purity, time itself, the unalterable and un-iterable experience of a pretechnical perception (as if there were any such thing). (3)

Coming six years after the first book in the series, Mémoires 1995 (1995) was an attempt to relativize the firm knot that is “Christine,” even though it may not be possible to unravel it. Because it also served as the catalog for a solo exhibition at the Winterthur Museum of Art, the editing was a collaborative effort between Furuya and the museum’s curator. This introduced a viewpoint that saw the works not as documents linked to the “death of a wife” but as pure photographic images. As a result, groups of photographs with similar tonality and stylistic characteristics (light tinged yellow in the evening, for example) resonated regardless of any connection to “Christine.” As well, a number of works related to the motif of Komyo (the couple’s son), who represents a presence that lies on the fringes of the point of singularity yet is unrestrained by it, or in other words a presence that did not have to change in the way that Furuya’s photographs had to change before and after the point of singularity, were added, while photographs from a series about Kosovo refugees which differed in both style and theme were also included.

Schattendorf, 1981.

Schattendorf, 1981.But to the extent that temporarily enclosing “Christine” in parentheses, allowing the photographs to be regarded as just photographs as others might regard them, and adding different motifs and themes may serve as a kind of relativization, such gestures were still not substantial counterpoints to the point of singularity. In other words, with the emphasis of this photobook placed on introducing Seiichi Furuya the photographer to a general audience, what ought to have been the most important issue was deferred. The artist himself was probably conscious of this. Because as if to atone for this injustice to Christine, in the following two photobooks in the series, Christine Furuya-Gössler Mémoires 1978-1985 (1997) and Mémoires 1983 (2006), he focused above all – including in the treatment of both motif and editing – on Christine. Furthermore, it was through concentrating on this point of singularity that Furuya discovered what Derrida refers to as “duration.”

Seiichi Furuya’s “Mémoires” photobook series:

Mémoires 1978-1988 (Camera Austria)

Mémoires 1995 (Scalo Publishers)

Christine Furuya-Gössler Mémoires 1978-1985 (Korinsha)

Mémoires 1983 (Akaaka Art Publishing)

Mémoires 1984-1987 (Izu Photo Museum)

Seiichi Furuya‘s “Mémoires” was on display at the Metropolitan Museum of Photography Tokyo from May 15 to July 19, and “Aus den Fugen” at the Vangi Sculpture Garden Museum, Mishima, from May 21 to August 31. All images courtesy the Vangi Sculpture Garden Museum.

-

Jacques Derrida, Copy, Archive, Signature: A Conversation on Photography. Stanford University Press, 2010 pp.9-10. Incidentally, according to Wilfried Skreiner the title “Mémoires” was taken from Derrida’s Mémoires, pour Paul de Man (1988), which was published the year before the release of the first Mémoires. (See Wilfried Skreiner, “Mémoires,” in Seiichi Furuya, Mémoires 1978-1988, Edition Camera Austria / Neue Galerie am Landesmuseum Joannneum, Graz 1989. p.102)

- Seiichi Furuya, Mémoires 1978-1988, Edition Camera Austria /Neue Galerie am Landesmuseum Joannneum, Graz 1989. p.94

- Derrida, pp.8-9

Archive

Critical Fieldwork: Observations on Contemporary Art in Japan 1-6