2008.11.11 – 2009.2.22

Gallery of Modern Art (Brisbane)

by Michael Fitzgerald

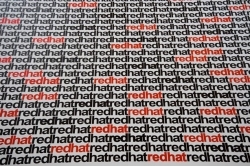

Vernon Ah Kee, Who let the dogs out (detail), 2008

Applied vinyl, Site-specific work for Contemporary Australia: Optimism Courtesy the artist

On 13 February 2008, Australia’s newly elected Prime Minister Kevin Rudd apologized to his country’s Stolen Generations for the past government policy of removing Aboriginal children from their mothers. Perhaps no other single event so perfectly captured the nation’s new-found spirit of optimism.

Nine months later, Brisbane’s Queensland Art Gallery (QAG) sought to test the national mood with Contemporary Australia: Optimism, the first of a new series of exhibitions based on the gallery’s acclaimed Asia-Pacific Triennial model. Comprising over 60 artists, with a dozen new commissions, the show seemed custom-built for QAG’s new Gallery of Modern Art, itself the shiny symbol of Brisbane’s cultural renaissance.

The curatorial challenge of holding a mirror to society at the same time as using the theme of ‘optimism’ as a satellite-navigational tool was put in the capable hands of QAG’s Julie Ewington, who identified “positivity, commitment, resistance, action” as her connecting thread. Audiences may have been seduced by the exuberance of color and scale that many of the artists favored, but the subliminal message was often less feel-good – as Vernon Ah Kee’s text work in the entrance foyer proved. Soaring three storeys high, Who let the dogs out (2008) saw this Indigenous artist’s previously minimalist aesthetic take on epic proportions under the artistic alter ego Red Hat. Ah Kee’s message was clear: only a nation that has addressed its racial prejudices can hope to move forward. (Written en masse, red hat reads as ‘hatred’.)

For many exhibiting artists, ambivalence proved a more sustaining inspiration than undying positivity. Darren Sylvester’s filmed recreation of The Carpenters’ 1970s Japanese garden and Scott Redford’s witty referencing of old Route 66 road signs found hope for the future in a yearning for the past. Most bittersweet of all was Kate Murphy’s party-hatted self-portrait, filmed crying during her session with an Irish fortune teller. Indeed, the fine line between tears and laughter was made especially pronounced, with Ewington tapping into Australia’s rich vein of comic humor. As participating artist Jane Turner, creator of the cult TV sitcom Kath and Kim, wryly observed: “When I laugh I cry.”

Optimism successfully captured this knife-edge mood of the moment. And no work better married the sardonic with the sentimental than Tony Albert’s Sorry (2008). This text mural, fashioned from kitsch Aboriginal artifacts Albert rescued from second-hand shops, was given a double-edged poignancy as rendered by an Indigenous Australian. Sorry, like Optimism itself, resonated strongly with mixed emotions.

Michael Fitzgerald is Managing Editor of Art & Australia.

[This review appears also in ART iT No. 23 Spring 2009]