Seiichi Furuya: The Disclosed Mémoires (Part II)

Christine Furuya-Gössler Mémoires 1978-1985 (1997) presents in chronological order from the time Furuya met her until her death photographs of “Christine” – who by then had become a categorical point of singularity – with each photograph accompanied by a brief explanation written by Furuya. The effect of the point of singularity is to take the collection of photographs that had become disconnected from the passage of time [aus den Fugen, or literally, “the time is out of joint” (1)] and reinsert them (einfügen) into linear time. Furthermore, in Mémoires 1983 (2006) 1983 which was published nine years later, photographs from – the year Christine began experiencing psychological problems, ie, the year that marks the beginning of the evolution of the point of singularity of her suicide – are arranged again in chronological order together with extracts from Christine’s diary. One would expect these two volumes, which focus exclusively on Christine and are limited to a single temporal axis and a period of one year, to be extremely centripetal. But I think what Furuya discovered through the centripetal act of pursuing the point of singularity and its origins was in fact “an extended continuation,” or the essential centrifugality of photography. “Strangely enough, when I viewed the photographs and read the text simultaneously, the circumstances that existed around the time I took the photographs were clearly recreated as moving images. Events of the past that I probably wouldn’t have been able to recall if the photographs hadn’t existed suddenly appeared before my eyes.” (2) In essence, photographs are things that sideslip.

Upon opening Christine Furuya-Gössler Mémoires 1978-1985, essentially what one finds is photographs of “Christine” as an innocent schoolgirl, a newly-married woman on her honeymoon, a mother, a model aspiring to become an actress, a highly strung woman, a sick woman, a gaunt woman, a lonely-looking woman…and finally a portrait of a deceased person, that is to say a document of the life of one woman. And yet at the same time one also finds commemorative photographs of a steady stream of Japanese visitors and photographs of distinguished people from the world of photography (John Szarkowski, Nathan Lyons, Allan Porter, Daido Moriyama) exchanging pleasantries with Christine, and as one reads Furuya’s comments the nature of the document changes completely and the photographs of Christine are reduced to photographs of an innocent young woman, a woman who seems to be enjoying her honeymoon, a mother embracing a child, a model striking a pose, a highly strung woman, a sick woman, a gaunt woman, a lonely-looking woman and a woman involved in photography supporting her husband. Furthermore, the document diffuses into the atmosphere of the times created by among other things the fashion, the photography world of the time, the Japanese who lived in Europe at the time and familiar tourist spots in and around Vienna. In addition, when one views Mémoires 1983 and reads Christine’s own words in the form of the extracts from her diary, the image one gets is of a lonely, neglected, emotionally tormented woman whose husband is too busy with work, whose rebellious son is monopolized by his grandmother and who suffers all the stress of a wife who wants to strike out on her own but is unable to do so. In other words, (although considering the tragic conclusion, it is hardly mentionable) her situation is not unusual. Christine is unraveled and is transformed from a singular existence that stands out from the rest to a plural existence within a particular world and a particular time. Indeed, in the words of Derrida, “Reference is complex; it is no longer simple, and in that time subevents can occur, differentiations, micrological modifications giving rise to possible compositions, dissociations, and recompositions, to ‘effects.'” (3)

The photobook Mémoires 1984-1987 is a rereading and recreation of the first book in the series, Mémoires 1978-1988, by Furuya, who by narrowing the focus from “Christine,” the point of singularity that pierces the viewer, to Christine the person, succeeded in unraveling his subject into compound space-time. The reconstruction based on the centrifugality/cross-sectionality of the photographs of that unforgettable day and time also represents the deconstruction of the point of singularity as the essence of modern photography.

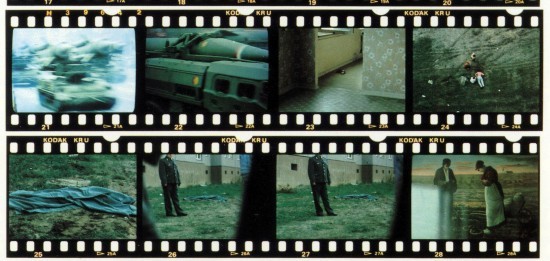

Potsdam, October 6, 1985 – Falkenberger Chaussee 13/502, Berlin-Ost, October 7, 1985, detail.

Potsdam, October 6, 1985 – Falkenberger Chaussee 13/502, Berlin-Ost, October 7, 1985, detail.The period “1978-1988” represents the time from when the artist first met Christine until the publication of his first photobook since her suicide. The manner in which on account of the emergence of the point of singularity all the events that occurred around that time – a group of photographs whose motifs are mutually unrelated – are removed from their original context and, as the inevitable, final, unbearable moment of October 7, 1985, approaches, brought together and connected centripetally as portents and reverberations of that moment, is handled as if the work were a piece of music. The finale comes in the form of a single contact sheet. A pair of sandals left by the window, a view from above of Christine lying face down on the lawn below. There is no way this shocking frame could have been made into a single photograph. No doubt there was an emotional reason behind this, but more than anything else it was because the aim of this photobook was to trace the emergence of the point of singularity and the resultant change in quality of photography, namely, the essence of “viewing” modern photography. In doing so Furuya had to avoid any hint of starting to tell the story of his tragic heroine from the sidelines and singing her praises through to the end of the final climax.

Potsdam, October 6, 1985 – Falkenberger Chaussee 13/502, Berlin-Ost, October 7, 1985

Potsdam, October 6, 1985 – Falkenberger Chaussee 13/502, Berlin-Ost, October 7, 1985The period “1984-1987,” on the other hand, represents the time Furuya spent with his family in East Germany. As something “complex” – a “subevent” – he singled out “East Germany (Dresden, East Berlin).” This is represented by none other than the scenes of East Berlin captured in the contact sheet that formed the finale to the previous volume. In other words, “the single, first and last time of the shot” already occupied “a heterogeneous time,” this “heterogeneous time” being the space-time of East Germany. In fact October 7 is the anniversary of the foundation of the German Democratic Republic and the streets of East Berlin were crowded with people attending a parade. “Because of the parade, both the ambulance and the police arrived more than an hour after I’d phoned them.” (4) By passing through the point of singularity of the day and time Christine chose to die, Furuya expands the “point” into the continuance of “1984-1987,” in effect using “Christine” as a path through which he exits into the space-time of East Germany (Dresden and East Berlin).

Both: East Berlin 1986

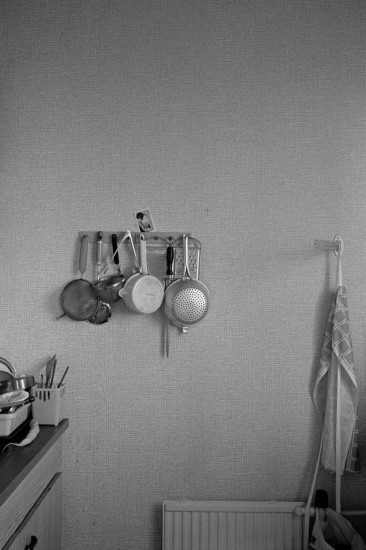

Both: East Berlin 1986Within these various snapshots we see glimpses of the “pleasures and days” of communist society. This view is different from the stereotypical view of “East Germany” of the “past” presented in recent German films addressing the reunification of that country. To be sure, the Berlin Wall fell and in the 20 years since then the psychological wall dividing East and West Germans has probably also fallen to an extent, but “East Berlin” itself will by no means fade away. For example, the collection of buildings in Falkenberger Chaussee (an area of high-rise apartment buildings around 30 minutes by tram from Alexanderplatz) where Furuya and Christine lived remains largely unchanged. Furuya’s photographs of East Berlin would fill former residents not with “ostalgie” (5) but with shock at how little things have changed.

Both: East Berlin 1987

Both: East Berlin 1987The “Mémoires” series has been disclosed. Over the course of 25 years, the situation in which every photograph was linked to Christine underwent a reversal, with Furuya able to venture into every photograph by way of Christine. Having said that, in the vast majority of cases the direction in which the photographs developed was towards a closed world that no longer existed. When Seiichi Furuya’s photographs do open up more in the direction of the present and the future, Christine will become a true exit enabling his photographs to branch off in all directions. This is something that can clearly be perceived, albeit only partially, in this latest photobook, Mémoires 1984-1987. With its fine selection of photographs that clearly show the artist has the eye of an orthodox snap shooter (the butcher’s next to the undertaker’s, the strangely cheerful eroticism of the high-cut swimsuits and bodybuilder’s briefs, the graffiti-free walls of Berlin…), what appear to be merely photographs of a listless family, the use of multiple exposure, landscape photographs with a short middleground focus, the various motifs (still lifes on tables, plants, mirrors, Christianity) that recur and mutually vibrate with just the right rhythm, references to the history of photography (Walker Evans), and the layout in which all these elements are naturally interwoven (6), this photobook offers the viewer a rich photographic experience.

Seiichi Furuya’s “Mémoires” photobook series:

Mémoires 1978-1988 (Camera Austria)

Mémoires 1995 (Scalo Publishers)

Christine Furuya-Gössler Mémoires 1978-1985 (Korinsha)

Mémoires 1983 (Akaaka Art Publishing)

Mémoires 1984-1987 (Izu Photo Museum)

Seiichi Furuya‘s “Mémoires” was on display at the Metropolitan Museum of Photography Tokyo from May to July 19, 21 and “Aus den Fugen” at the Vangi Sculpture Garden Museum, Mishima, from May to August 31. All images courtesy the Vangi Sculpture Garden Museum.

-

Hamlet, Act 1, scene 5, line 188; the title of Furuya’s solo exhibition, “Aus den Fugen,” references this line from Hamlet.

- From the photographer’s foreword to Christine Furuya-Gössler Mémoires 1978-1985 (Tokyo: Korinsha, 1997); emphasis the author’s.

- Jacques Derrida, Copy, Archive, Signature: A Conversation on Photography. (Stanford University Press, 2010) pp.8-9.

- From the photographer’s afterword, “Adieu-Wiedersehen,” in Christine Furuya-Gössler Mémoires 1978-1985.

- A portmanteau of the German words Ost (east) and Nostalgie (nostalgia). It refers to nostalgia for certain unrefined aspects of life in the former East Germany, such as the cheap yet charming East German designed plastic products.

- Combined with the fact that the death of a loved one serves as an important motivating factor, Seiichi Furuya’s layout (in particular his use of white space and the rhythm of double-page spreads and vertical and horizontal positioning), his editing, in which works are placed side by side with no distinction between past and present and seemingly unconnected elements such as still lifes on tables and slices of everyday life are interwoven with the central motifs, and the singular-plural essence whereby from a single photograph he slides into multiple photographs all call to mind the work of Wolfgang Tillmans. In Tillmans’ case, certain photographs are continuous with others on account of the images themselves or the equivalence of the superficial eroticism of the subject (see Minoru Shimizu “The Art of Equivalence” in Wolfgang Tillmans: Truth Study Center, Taschen 2005), but in Furuya’s case, the shift from one photograph to another is accomplished entirely through the individual “Christine.” One could say that Christine is the kochuten (“paradise in a jar”) of photography.

Archive

Critical Fieldwork: Observations on Contemporary Art in Japan 1-6