Neither decolorized nor faded – The latest color photographs by Daido Moriyama

(Part 2)

Let us summarize the main points so far.

1) Looking back at Daido Moriyama’s “photographs of memories” from the second half of the 2000s onwards, we see they point to the 1980s, when Moriyama’s photography gradually changed. Moriyama, who had already bid farewell to Modernism in photography in the 1970s, was unable to find a new direction and returned to the historical roots of photography (“What was photography?”), relying on a style that saw him abandon himself to Light and Shadow (1982) (= “the real” in the darkroom) on the understanding that these historical roots lay in sensing here and now the light of the past. The 1980s saw Moriyama breakaway from this style (1) and make a fresh start from a new photographic starting point. And it was amidst this change – through the three Hysteric works of the 1990s – that the style he continues to use to this day emerged. The reason why Moriyama’s current photography is referencing this period is probably because he is seeking to use the medium of digital color photography to pursue a path different from the “hysteric” of the past.

2) This gradual change took the form of an awakening from the fetishism of sensing and responding to light and a shift to taking snapshots that capture sober everyday life as it is.

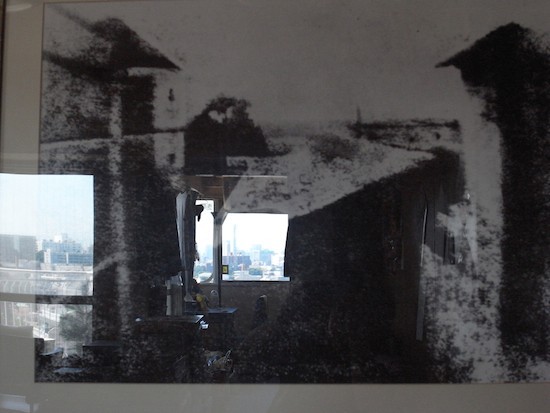

3) Among the distinguishing characteristics of this new color photography are a) a breakaway from the old faded colors (another expression of sensing and responding to light), and b) collage-like composition, including the use of strong contrast that renders the images graphical (in particular, the use of black that fills the picture plane), the bold division of the picture plane, and the introduction of posters, mirrors, and so on.

Lines dividing the picture plane vertically, and the collage-like effect of signboards.

Lines dividing the picture plane vertically, and the collage-like effect of signboards.  The view through windows incorporated (= collaged) into a photograph by Niépce.

The view through windows incorporated (= collaged) into a photograph by Niépce.  Contrast that renders figures black.

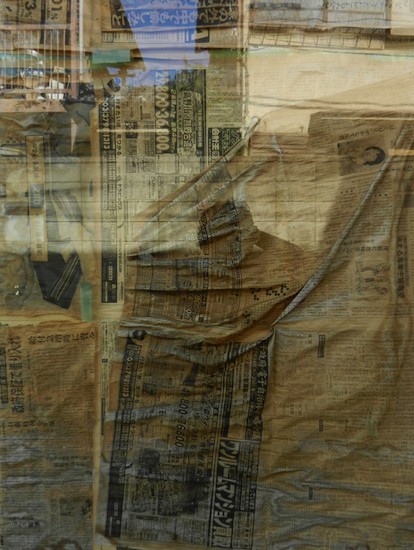

Contrast that renders figures black.  Newspaper, glass, reflected scenery (walls + background), the shadow of the photographer. A masterful five-layered collage.

Newspaper, glass, reflected scenery (walls + background), the shadow of the photographer. A masterful five-layered collage.All: Daido Moriyama – Tokyo (2012) © Daido Moriyama, Courtesy Taka Ishii Gallery and Office Daido.

Looking at 2011’s Color Photograph and the two collections of color photographs that appeared this year in quick succession, Record No. 21 and Color, on the basis of the above, it should be clear that Moriyama’s color photography is transitioning from emotion/light/color as aesthetic and erotic grayscale to matter-of-fact, dry color, or in other words digital color in which the contrast has been raised to an almost abnormal level so that the colors are saturated, producing an effect like the dark shadows of full summer. There are exceptions that hark back to the old “faded colors,” but most of the new color works are marked by an all too refreshing literalness, ie absence of sentimentality, such as can be seen in the photographs from after Moriyama passed through the period of dislocation in the 1980s (from A Journey to Nakaji onwards). It is none other than the collage-like picture planes and photographic memories that constitute the very elements supporting this literalness. To put it another way, they serve as the motive power guiding each photograph not downwards in the direction of a single, deep meaning, but sideways to the next photograph, the next fragment. In terms of a superficial analysis, we could probably say the following: Daido Moriyama takes remarkably standardized colorful digital color scenes and transforms them not by decolorizing them to produce beautiful black and white images (light and shadow) and not by fading them by exposing them to light, but transforming them through the power of collage and memory into plain, which is to say, colored, miscellaneous scenes of the everyday. But why does collage enter the picture, so to speak? What does this say about the relationship between digital photography and collage?

The Daido Moriyama of the late 1970s discovered in the work of Nicéphore Niépce “What photography was.” Taking into consideration the changes he went through in the 1980s, his farewell letter to that decade, during which he came under the influence of Niépce and “light and shadow,” was 1990’s Lettre a St. Lou. In light of characteristics a) and b) above, one can only conclude that Moriyama’s photography (not Moriyama himself) is once again referencing photography’s past. As I argued in my first column on Taiji Matsue, digital photography is not photography that imitates analog photography using digital technology, but photography that frankly does not belong to the conceptual frame analog = Modern. As such, digital photography occasionally takes on a quality that enables it to bring back into existence the state of photography at around the time of the emergence of this frame. To put it another way, as well as being tied to the true character of the earliest photography devoid of this Modern frame (pre-establishment), it tends to recreate the very emergence of this frame based on current awareness, including knowledge of digital technology (post-establishment). In this sense, Daido Moriyama’s digital photography also appears to recreate the past. It may sound strange, but in fact “collage” is the essence of photography, visible – with different shades of meaning, of course – in the work of both Stieglitz and Evans. Let us consider Stieglitz’s “The Key Set.” (2) The disillusionment with Pictorialism and the shift to “snapshots” that capture sober everyday life as it is, the breakaway from faded color brought about by the control of Autochrome to black and white “chiaroscuro,” and composition as collage… Here we can detect as is the characteristics of Moriyama’s digital photography.

Alfred Stieglitz – Katherine Stieglitz (ca.1910)

Alfred Stieglitz – Katherine Stieglitz (ca.1910)An Autochrome adjusted so that the colors appear pictorially faded. As the name suggests, Autochrome was an automatic process, as is color photography today, and for this reason the original colors are more vivid and balanced.

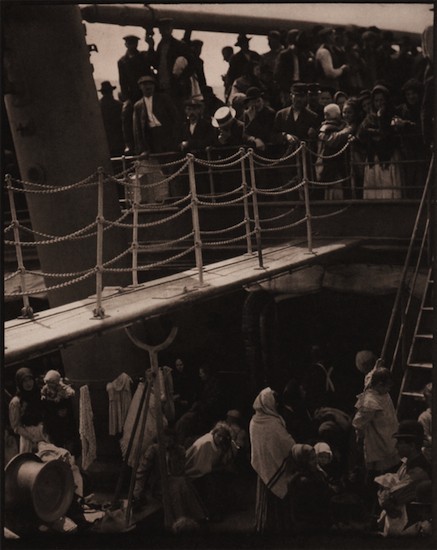

Alfred Stieglitz – The Steerage (1907)

Alfred Stieglitz – The Steerage (1907)A snapshot that foreshadows the establishment of Stieglitz’s own philosophy of photography as well as the collage-like composition he would discover and whose significance he would appreciate later.

Alfred Stieglitz – Fountain, photograph of the readymade by Marcel Duchamp (1917). Courtesy Succession Marcel Duchamp, Villiers-sous-Grez, France. © 2006 Marcel Duchamp / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris / Succession Marcel Duchamp

Alfred Stieglitz – Fountain, photograph of the readymade by Marcel Duchamp (1917). Courtesy Succession Marcel Duchamp, Villiers-sous-Grez, France. © 2006 Marcel Duchamp / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris / Succession Marcel DuchampDuchamp’s Fountain placed on a pedestal and photographed together with Marsden Hartley’s painting The Warriors.

In addition to the above, in A Snapshot, Paris (1911) one can see a bold division of the picture plane, while in 291 – Picasso-Braque Exhibition (1915) Stieglitz has created a collage by combining different subject matter, including collages by Picasso and Braque, both of which rest on a shelf, an African sculpture, a wasps’ nest and a brass bowl. Note that neither of these photographs depicts the works as they originally appeared in the exhibitions concerned. (3)

“Collages” of signboards, wording, and so on also appear frequently in the work of Walker Evans, who loathed Stieglitz, which is at odds with his popular image as a producer of pure, unadorned documentary photographs.

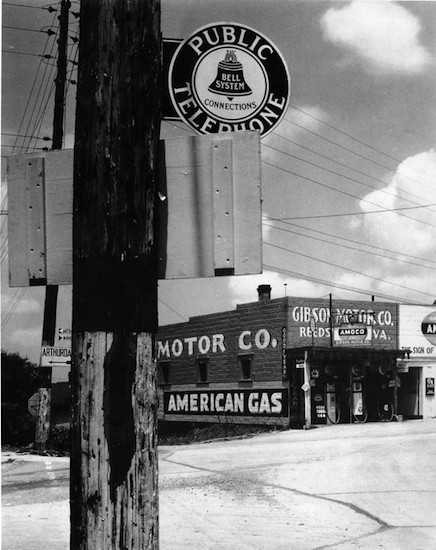

Walker Evans – Gas Station, Reedsville, West Virginia (1935)

Walker Evans – Gas Station, Reedsville, West Virginia (1935)An example of a photograph in which the framing alone gives rise to a fine layered collage.

Walker Evans – New Orleans street corner, Louisiana (1936)

Walker Evans – New Orleans street corner, Louisiana (1936)Might it be that Moriyama’s photography is returning to the “collage” of straight photography just as it once returned to Niépce’s “light and shadow”? I think one could say this is the case. At the same time, however, he is adding even stronger contrast and adjusting the colors digitally. (To be continued)

-

That his reunion with Takuma Nakahira following Nakahira’s recovery from amnesia had a large part to play in this breakaway is clear from the fact that the “memories” of Moriyama’s photography around the period 2006-08 point to Nakahira’s work from the 1980s. For further information see Minoru Shimizu, “To Hawaii/From Hawaii” in Hibi Kore Shashin, Gendaishicho Shinsha, 2009.

- Sarah Greenough The Key Set – Volume I & II: The Alfred Stieglitz Collection of Photographs, (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 2002).

- See The Key Set – Volume I, p. LV, Note 115.