I try to place the spectator in the dialogue, to make them find their own orientation.

This Bangladesh-born, British artist and movie lover has produced a string of works referencing the history and vocabulary of film, focusing on the 14 letters c-i-n-e-m-a-t-o-g-r-a-p-h-y to explore ways to look at and read the world. We talked to her about her relationship with her subjects and the audience.

Interview: Milovan Farronato

Portrait: Martina della Valle

– Antonioni, Resnais, Bresson, Bunuel, Fassbinder, Cavani, Fellini, Godard, Roeg are some of the authors you appreciated as a teenager at the independent cinemas in London. You love cinema and your work clearly references the “cinematographic lexicon”. In your early work Tuin (1998) you quote a key scene from Fassbinder’s Martha: the one where the husband’s sadistic and stifling gaze revolves 360° around the female character. You shot a similar scenario, but reversing the principle by assuming the points of view of both characters, right up to the revelation of the film crew and the camera itself. Would it be safe to say you don’t simply adopt cinematic language, but subvert it?

Tuin, 1998,

Tuin, 1998, 16mm film on single screen and two DV projections with sound on CD 6mins looped.

Courtesy Jay Jopling and White Cube, London

Yes, if by subverting you mean disrupting rather than corrupting the conventions. Tuin tries to disrupt the way the narrative is read, but also tries to build another way of reading or visioning a narrative. It places counter or contradictory narratives within the same realm. The works I made during this period, such as Screen Test / Unscript and Dead Time (2000) or Director’s Cut (Fool for Love) (2001), can all be seen as negations of cinema employed in a dialectical process ? critically breaking down a framework to make new resolutions which themselves can then be broken down. They are investigations into the forms, methods and language of filmmaking as an art.

In Screen Test / Unscipt, I made a collage of soundtracks from familiar avantgarde films (in many different languages) and combined them with random screen tests of some people I knew, simply to see how to get the sense of cinema. It was a work with the elements of lights, camera and subject (or character). The lines of dialogue were not really meant to form a logical “script”, but be random quotes that could conjure up a mood or create an answerless question. In a way this also subverts the illusion of film.

‘Writing with the camera’

– In both Screen Test / Unscript and Tuin, the “mechanical eye” peers into the scene. Why is it so important for you to show what is beyond the mystery of cinema and reveal the otherwise secret functioning of the magic lantern? Occasionally you as the director even appear, breaking the cinematic illusion with some Brechtian reminder…

Screen Test/Unscript, 2000,

Screen Test/Unscript, 2000,16mm film with sound on CD 8 mins.

Courtesy Jay Jopling and White Cube, London

Well as you say it’s like a Brechtian distancing device. And that makes the performance or the image more intense. I’m interested in the way the image is constructed and believe that actions like revealing the camera can heighten your relation to what you watch. It tries to place the spectator into the dialogue.

Each film in which I’ve revealed the camera, myself or apparatus has a different rationale as to what it reveals. In Screen Test / Unscript, the passages of the ‘characters’ montaged with those of the lights illuminating them (necessary for the film exposure) and my own image with the camera are essentially reflexive images. The moment you see the camera pointed at you, you also see a mirror effect. In this installation I displayed the projector in the room, and so you see the light that went into the camera onto the film, coming out of the projector onto the screen.

In Tuin, I gave the characters video cameras while staging the scenes. They were handheld devices that created a documentary-style perspective whereas the 16mm film version illustrates the actual 360° turn in its most theatrical illusory way. The film and the two subjective points of view created a type of echo chamber, into which the spectator has to find their own orientation.

– I understand your upcoming project deals with these issues as well, and that you just concluded a residency in New Zealand where you had the opportunity to start the production and test experiments of a new film…

I found in my notebook the sentence ‘writing with the camera’ and this inspired me. The word ‘cinematography’ is basically ‘writing with movement’, or better, ‘to record in movement’, just as photography is ‘writing in light’. I wanted to write the word itself with the camera, to realize a sort of tattoo on a landscape where the starting and ending point coincide.

When I arrived in New Zealand I began to develop the many possibilities involved in this idea and to look for someone that could deal in the effects of film in the most appropriate way. I found a motion control pioneer and operator called Harry Harrison, who was perfect; he had worked on the remake of King Kong and on all of the The Lord of the Rings. I met him at a big old warehouse full of everything concerned with the technical side of cinema. He loved the idea and committed. New Zealand gave me the opportunity to write my chosen word on the most mystical of landscapes, but I ended up selecting Harry’s workshop as the location for the shoot. The close-ups on all that stuff and technical equipment reveals a surreal panorama, abstracting into a sort of cosmology within the densely packed space. The idea was to start from the outside depicting the “c” on the sky and then moving with the other 13 letters into the interior of his space. What intrigues me is how the image can be subordinated by the movement of the camera drawing or writing the letters. For example a ‘c’ could make a close-up around a face, but in effect could omit the face itself. Or depicting the ‘i’ could show a portrait from the neck to the feet and move to the face to dot the ‘i’. And for those who identify the ‘code’, the image and their pictorial effect are going to lose importance; it’s an interesting balancing act of what becomes significant.

‘Iconoclastic’ because…

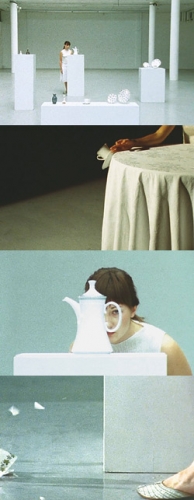

– The construction and history of Be the First to See What You See as You See It are quite complex and based on several layers too. The title refers to both a polemical sentence by the film theorist Robert Bresson about the importance of experiencing the moment and to the actual writing you did on the simulacrum facade of London’s Curzon cinema for the sculptural installation Curzon at Spike Island. Then you took inspiration from a scientific archive film, a slow-motion study that portrayed a man smashing a vase full of water. In your film he is replaced by an elegant woman who gracefully smashes bone china tea sets (that you found in charity shops in Clevedon, West England where you were also doing research for Curzon). These artefacts have been perfectly located on white plinths against a backdrop of ultramarine blue. And so with Be the First… you ended up with a very iconoclast image. What was your intention?

Be The First To See What You See As You See It, 2004,

Be The First To See What You See As You See It, 2004, 16mm film with sound 7mins 30secs.

Courtesy White Cube, London

Although my works do engage subversive or inversive gestures, I think it was more the role of the pedestal that made the work ‘iconoclastic’ than the smashing itself. I originally intended to make the film using balloons exploding in slow motion (which I since did in my more recent film What is a Thought Experiment, Anyhow?). But by the time of the shooting, I had found the cups and was working at the large museum at Spike Island in Bristol, so a lot of the work began to shape itself naturally. I actually found the pedestals in one cupboard and the paint in another! I had also been told that the site of Spike Island had been a teabag factory up until only 10 years prior. There are amazing images I found soon after that show the ‘museum-like’ space full of machines and workers. There was a poetic moment when I thought about the gesture of smashing the delicate china objects as one that might resonate with the factory workers.

But the meanings were not prescribed (as with almost all of my works). Janet Owen, who wrote the text that accompanied my UCLA Hammer presentation, made a reading of her own referring to my Bangladeshi origins and the smashing in relations to the fractured and broken British colonies. I think my work allows you to use different prisms through which to read it.

– In Bangladesh you realized First day of Spring (2005), which suggests something different to your usual working process, something of an impromptu quality, in that it was produced in about 24 hours. Conditional Probability on the other hand emerged from two weeks of shooting at North Westminster Community School – a progressive, multiethnic London school, somehow a counterpoint to the ancient colonial status of Great Britain. There you also accepted an invitation to chat with the young students about everyday experiences focusing on the necessity of adaptation in that specific age group and context.

My way into a project is different each time. When I made First Day of Spring in Bangladesh it was one of four film ideas that came to me in one day all of which were made in three days. Be the first… , as you mentioned, rooted back to influences that came from years before and coincided with spontaneous ideas and encounters. For the school commission I spent in all about nine months of preparation before filming.

In First Day of Spring I allowed the rickshaw pullers you see to take ‘center stage’, to counter the marginal roles they play within the socio-economic climate. For Conditional Probability, I wanted to portray the students in their own film, but using neither the methods of conventional documentary or narrative dramas. What emerged was a four-part work that correlates four different ways of engaging with the students. In one of them we see the actual screen tests, each student replying to a set of questions such as ‘do you see your life like a film?’ We get a sense of who they are in terms of names, ages, and country of origin.Interestingly, a large number of the students were from recent war zones, which in itself was a story. But in previous conversations the students didn’t reflect on their histories; instead they looked at their present situations and status or towards the future. In another part you see the students participating in a workshop, making up characters based on objects they have with them – things like mobiles, iPods, cigarettes, condoms. This was my way of connecting directly with the visions and voices of the students. The main part consists of a set of dialogues from a loose script the students play out to form a collection of vignettes that create a type of snapshot of a place at a point in time, both fictional and representational.

A solo show that isn’t a me, me, me thing

– Next year you’ll have an important travelling exhibition for which I understand you will not merely select a series of relevant works and create a pathway, but rather conceive it with a more critical and theoretical approach. I think about how Mike Kelley conceived Uncanny, a group exhibition that ended up being one of his biggest installations, or the solo show Rirkrit Tiravanija realized for the Pompidou: no works on display, just an empty space where a few performers recalled some of his works. Which will be your approach?

For this opportunity I want to consider the model of the solo exhibition as part of the new project. Although I will make new films, I want to think about making a series of sketch-like films rather than one major manifestation. I think the ‘c-i-n-e-m-a-t-o-g-r-ap-h-y’ work is a starting point for this. I want the show to be like a mosaic that refers to many aspects of my practice. I also want to invite other artists to work with me to build environments or projection spaces that are an alternative to the “black cube” format, to make a site in which I will extend the invitation to show films or works by other artists, and where possible, work with aspects of the collections to look for resonations to the show. I was really impressed with Elke Krystufek’s solo show Liquid Logic at MAK in Vienna, where she critically investigated her position and process within the institution.

I feel huge solo exhibitions often extract the artist out of a context of exchange and collaboration, so I’m trying to conceive of a solo show that isn’t a ME, ME, ME thing!!

Originally printed in ART iT 16 Summer/Fall 2007

Runa Islam

Born 1970 in Dhaka, Bangladesh. Lives and works in London. Received her BA from Middlesex University/Manchester Metropolitan University and MPhil from the Royal College of Art, London. She attended the Rijksakademie, Amsterdam and had residencies at Spike Island, Bristol; IASPIS, Stockholm, and Two Rooms, Auckland. Recent solo shows include the Bergen Kunsthall (2007), Serpentine Gallery (2006), UCLA Hammer Museum and Camden Arts Centre (2005), and ShugoArts (2004). She has participated in the Sharjah Biennial (2001), Taipei Biennale (2002), Istanbul Biennale (2003), Venice Biennale and Prague Biennale (2005), Sevilla Biennale and Gwangju Biennale (2006). In 2008 the SMAK in Ghent will host a major solo retrospective, parts of which will travel to the Zurich Kunsthaus and the Modena Galleria Civica.

Milovan Farronato is director of Viafarini, Milan, and Associate Curator of Galleria Civica di Modena, Italy.