– I’d like to talk about the selection of Japanese artists this time – Nara/graf, Ohmaki Shinji, Nawa Kohei, Sawa Hiraki – why did you choose these artists?

With Nara/graf I was thinking about collaboration, partly in light of the North Korean (DPRK) selection. Because all work is collectivized in North Korea, making art is also collectivized, and artists work in studio structures together, often on the same painting. So I was curious to consider a range of collaborative models and artistic projects that could sit in dialogue. I thought Nara/graf were very interesting because they embrace a completely different ethos and exist in a very different political climate. However there are certain similarities in terms of a group of people with different skills interested in working together to achieve something.

Works of the North Korean Mansudae Art Studio

– It’s interesting you find them similar to the North Korean system.

We also have our veils. Because we from the Gallery can’t visit, we haven’t been in a position to go any deeper with a place like North Korea, but this time we did, working with co-curator Nicholas Bonner who has long-standing relationships with a number of artists and filmmakers in North Korea. And the result is really an exhibition within the big exhibition; there are 69 artworks in that space.

– How about the other Asia countries like Turkey, Iran and Tibet, which you’ve included for the first time this year?

West Asia was important because it is a foundational cultural language that extends from that part of the world through South Asia and on to Indonesia, Malaysia, and Fiji. It is important to look to the root and open up that dialogue.

– I agree that the Iranian and Turkish works have had a strong influence on the East part of Asia, especially Islamic patterns. But Gonkar Gyatso’s work is very different.

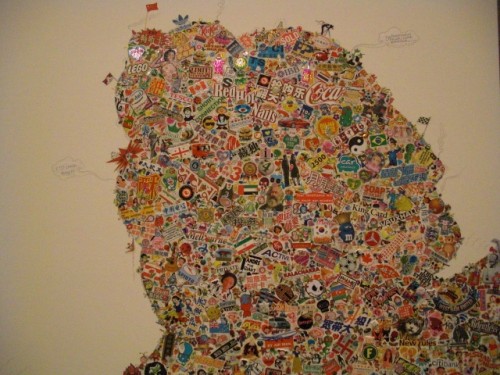

Gonkar Gyatso Reclining Buddha – Shanghai to Lhasa Express (detail)

You’re right, he’s not part of West Asia. He’s an artist we wanted to include, who comes from Tibet. He brings very interesting political issues to the fore, especially working with Buddhist iconography, consumer culture, again urbanism, and popular, everyday imagery. And a very strong artist now I think.

This APT also marks the first time we are showing Cambodia, so we’ve looked at three generations of Cambodian artists from the late Svay Ken to Sopheap Pich and then Vandy Rattana. Rithy Panh, in the cinema segment, like Sopheap, belongs to the middle generation. Very strong and moving films.

The importance of the diaspora and other

– Speaking of the cinema segment: I was very astonished when I saw the selection for this year – especially Ang Lee and Kitano Takeshi. I’d like to know why these filmmakers were chosen.

Poster for APT Cinema (Ang Lee’s Lust, Caution)

Ang Lee because it is very interesting to see how he works with Hollywood cinema, with the mainstream from here – being Taiwanese.

– So you consider him part of the diaspora?

Yes, like Runa Islam. The diaspora is vital in APT because it unsettles. It makes you rethink notions of indigeneity and authenticity.

– But Kitano is quintessential Japanese.

Kitano may be wellknown in Japan, but not here in a popular sense. And we are curating for our audiences here. We are not curating particularly for international audiences, although they come – which is great. Primarily our audience is a local audience. So what is familiar to you, may not be familiar to me.

Another journalist asked me about ‘biennale fatigue’ and I said ‘well, maybe for you, but not for most people.’ Most people don’t go to every single biennale in the world. Actually, most people hardly ever go to biennales. They are most likely to go to their local one, because that’s the forum in which contemporary international art is made most available. Biennale fatigue only exists in a tiny percentage of art world people who have the funds and the time to travel in that way.

– The so-called ‘biennale jet set’.

And how many are they when you consider the population? For us what’s relevant is to communicate to our local audiences, and to Australian audiences, ideas about contemporary art.

– Which brings us back to the question, what is contemporary art? Especially in a non-Western region.

It’s a big question, and a good question because it is open-ended, and open to interpretation every time. So Pacific Reggae: how is this contemporary art? The presentation of art from North Korea: how is this contemporary art? The Vanuatu selection of customary sculptures from North Ambrym…. It is a good question in its attention; it’s a bit awkward, uncomfortable, but important. You don’t want it to all meld into some kind of all-encompassing pluralism, where just because it’s being made now, it’s contemporary. Take for example Pacific Reggae, this project (performances and music videos) provided a great platform to think about how indigenous peoples use both visual and oral forms to make culture and in this case mobilized the activist energy intrinsic to reggae to talk about local conditions of performance and politics. We didn’t feel compelled to be tied to specific canons, because there are so many art histories, local art histories; we should hear them.

Vanuatu sculptures

Looking at the North Korea portraits, for example, we see how important brush and ink is. This goes back to the history of brush and ink painting in East Asia – Japan, China, Korea. Brush and ink, calligraphy – these canons belong to East Asia. But these portraits are also made using oils, which is imported from the West, and comes to Korea via Japanese studios.

– But what about the popular icons and popular culture, like anime, or figures, or manga? These were first born in Asian countries like Japan, or Korea…

They are part of those canons that are very local; they are from inside those cultures, and spill out.

– But in spilling out, they’ve changed.

Yes, they change. And it happens in two directions. That’s why ‘other’ is good: the other is inside you too, not just over there.

Suhanya Raffel

Born in Sri Lanka. Curatorial Manager, Asian & Pacific Art at the Queensland Art Gallery. With degrees in Fine Arts and Museum Studies from the University of Sydney, she has organized numerous exhibitions in the UK, Australia and South Asia. She has been a member of the curatorial team for the Asia Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art (APT) since 1999, assumed her current post in 2001, and is the lead curator for this year’s APT6. Among her recent curatorial projects for QAG are Andy Warhol (2007-08) and The China Project (2009).

< Back to Index : "The 6th Asia Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art"