A cynical beginning – TOLOT heuristic SHINONOME

The end of March was art fair week in Tokyo, but I found the art space TOLOT heuristic SHINONOME, newly opened in Shinonome, more interesting than the likes of Art Fair Tokyo and G-Tokyo, which tend to feature the same old familiar faces and similar artwork. The space was created by the owner of TOLOT (a printing and software development company) by renovating the second floor of the company’s office building, and while we tend to think of Shinonome as being out of the way, the closest station, Shinonome, is on the convenient Rinkai Line, so the space is actually very accessible.

Left: TOLOT heuristic SHINONOME. Right: Jose Parla – Haru Ichiban / First Wind of Spring / Through the Tokyo Alleyways – Her Voice Sings… (2013). Photos © Hisayoshi Osawa

The entire space consists of galleries in the form of giant boxes arranged in two rows (see photo on the left) and the open space that surrounds them. It is in the unpartitioned gallery (see photo on the right) that works by artists represented by Tomio Koyama Gallery, Taka Ishii Gallery, Wako Works of Art and SCAI The Bathhouse, paintings created onsite by José Parlá, and other works were displayed as part of the inaugural exhibition. From June, solo exhibitions of work by artists from each gallery will be held in turn, starting with Wako Works of Art. The partitioned boxes comprising the remaining gallery space house a special exhibition space (at the time a Tokyo Frontline special exhibition that shifted from 3331 Arts Chiyoda), Yuka Tsurano Gallery, and G/P + g3 / gallery.

Nobuyoshi Araki’s boat (numbered edition, new print) and Daido Moriyama’s dog (rare vintage print from the negative) (according to Atom Suematsu). Photo © Hisayoshi Osawa

The Tomio Koyama Gallery exhibition space, the porcelain skull in the foreground by Kasuyo Aoki.

Tokyo Frontline Project “Trick Dimension”

What interested me, however, were not in fact the contents of the boxes, but the “permanent display” in the open space that surrounds them. This is because it is here that the ideas of the space’s owner/collector with regard to the world and art today most clearly and concisely manifest themselves. There are many art spaces around the world operated by collectors, but it is unusual for such clear opinions to be incorporated into such a space, particularly in Japan.

This “permanent exhibit,” which will in future function as the open space around all the exhibitions held at heuristic SHINONOME, consists of Gerhard Richter’s 8 Glass Panels, a sculpture from Jonathan Monk’s “Many Others” series that references the epitaph inscribed on Marcel Duchamp’s grave, “D’ailleurs, c’est toujours les autres qui meurent” (“Besides, it’s always the others who die”), part of a full-size replica of the Statue of Liberty by Danh Vo, and the architectural white cubes posing as a work by Donald Judd. That’s right, the themes are death, the end = the objective, the pure essence of art, and “freedom” in our present society.

Gerhard Richter – 8 Glass Panels (2012). Photo © Hisayoshi Osawa

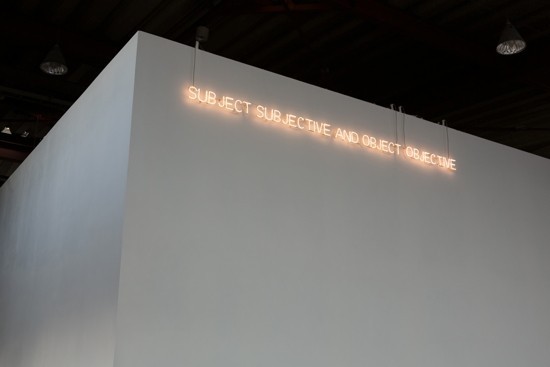

Joseph Kosuth – Subject and Object (1966). Photo © Hisayoshi Osawa

Jonathan Monk – Many Others II (2012). Photo © Hisayoshi Osawa. An old gravestone inscribed with the epitaph “Mein Jesu Barmherzigkeit” (Jesus, have mercy) reworked to read “D’ailleurs, c’est toujours les autres qui meurent” (“Besides, it’s always the others who die”).

Danh Vo – We the People – B4.2 (2011)

For Richter, Duchamp is a thorn in his side. (1)

The basis of Richter’s art consists of “the manifestation of Schein (focusing attention on the base surface of all manner of visuals, be it a screen or a mirror surface)” and “readymades,” and his myriad styles all result from various methods of manifesting Schein. The first person in art history to make “Schein” the theme of his work was Monet in his later years, and Richter is the last artist in a tendency in contemporary painting (painting based on layers) that began with Monet’s water lilies (water surface = painting that manifests layers). It is for this reason that Duchamp, who abandoned painting and began producing readymades just when this tendency emerged, is such an important reference point. Duchamp intervened in order to place ready-made articles in a state of “humdrumness/indifference” (readymade), while Richter alters photographs (found photos) with oil paint in order to turn them into Schein (readymade). Shocked after viewing a Duchamp exhibition in Krefeld in 1965, Richter painted Ema (Nude on a Staircase) (1966), which he followed a year later by making the sculpture Four Panes of Glass (1967). Thereafter he continued to express as “readymades” the painting system of “layers,” right up to 2002’s “Standing Panes.” As installations, these works reflect on transparent surfaces (ie, turns into Schein) all of the scenery around it, in which sense the Schein is the readymade glass panes while the monument formed by the standing glass panes is a grave marker for “the last painting.” At the same time, because Judd’s boxes were paintings as pure skeletons that extracted the framework of painting alone in the form of foreshortened space or boxes, the Judd-like white cubes here are also an example of the Richter/Duchamp/Monk lineage.

On the other hand, Kosuth’s neon work subject subjective and object objective, which shines light over the graveyard of these skeletons, points to another extremity of art. Four positions can be derived from the two pairings subject/object and subjective/objective. These are subject subjective (the subjective subject = the self thinking this on its own), subject objective (the objective subject = the self viewed from another’s perspective), object subjective (the subjective object = the world as imagined by the self) and object objective (the objective object = the world of others). Of these four, Kosuth rejects subject objective and object subjective, which is to say the so-called transcendent positions according to which one views oneself from outside oneself and interprets this outside world oneself, leaving as “pure” positions the remaining two, namely the isolated, socially withdrawn subject and the completely indifferent object. The key to this work is the “and.” It is as if Kosuth is saying that the direct linking of these two socially irreducible items alone is the pure essence of art.

The art in question here is 20th-century art, and because for 20th-century art “freedom” was none other than the reduction of things to their pure essence, what we see here is the graveyard of 20th-century art, the 20th century being an age in which wars broke out and refugees proliferated everywhere in the quest for freedom and in the name of freedom… In contrast to the graveyard of skeletons illuminated by the light of pure essence, the work by the Vietnamese-born Danish artist Danh Vo (2) takes the form of a piece of 21st-century conceptual art that raises fresh questions concerning the 20th century. The work is open to interpretation. Does the dismembered body of the Statue of Liberty suggest that the ideal of “freedom” is now collapsing? Or do the parts of the Statue of Liberty scattered widely around the world suggest that “freedom” still exists in the world, albeit it fragmentarily?

The message of this open space overall, however, is probably something like the following: From the late 1960s to the ’70s (3), postwar society transitioned from the modern to the postmodern. During this period, contemporary art, which emerged at the beginning of the 20th century, converged with increasing speed towards a single ending as if driven by this change in society, arriving at “freedom” through the reduction of this ending to pure essence as an objective. Thereafter, throughout the ’80s and ’90s, contemporary art around the world either repeated this (strangely theological) process in the same order, only 10 or 20 years late, regressed to a stage before this graveyard, or tinkered with the headstones in the graveyard. In other words, the importation of “Western contemporary art,” the production of effect-laden craftwork and the charming appropriation of conceptual art have amounted to nothing more than illicit liaisons in a graveyard. In order to get out of this graveyard, perhaps we need to reset this state of affairs before thinking about freedom in 21st-century art. (4)

-

See also “Gerhard Richter: strip – abstract painting no genzai” (abstract painting now) Bijutsu techo, March 2013, and my essays on Gerhard Richter “Duchamp no momakuka” (The retinaization of Duchamp) etc, in Minoru Shimizu, Shashin to hibi (Photography and the everyday), (Gendaishicho-shinsha).

- Vo’s family fled Vietnam as boat people, and sought asylum after being rescued by a Danish vessel.

- In advanced countries such as the US and UK. One of the conditions for the advent of a post-modern information/capitalist society is the accumulation of a certain amount of wealth, as a result of which this transition occurred in the late 1970s to ’80s in the defeated nation of Japan, and even later in the former Communist bloc, China and South Korea.

- If there is something lacking from this space, it is early period Pop art. Pop artists were the first “dogs” (the word “cynic” derives from the Ancient Greek kynikos, meaning dog-like) who defied the compulsive “freedom” of modern art while responding cynically to post-modern society. Having said that, Warhol would not do after all these years, in which case I would probably have someone like Sterling Ruby fill in as a 21st-century pop artist.