Video and rhythm: Akira Miyanaga’s arc (2011) and scales (2011) (Part 2)

Still from arc (2011), HD video, 7 min 30 sec. Courtesy the artist and Kodama Gallery.

Still from arc (2011), HD video, 7 min 30 sec. Courtesy the artist and Kodama Gallery.In minimal music, “repetition” is significant in the respect that it produces auditory layers. The composition of minimal music is none other than a process of collage in which patterns are repeated to produce layers that are then staggered and superimposed. (1) In music, layering refers not to “parts” or the staves on musical scores as seen from the composer’s point of view, but to the awareness of “layers” that forms in the mind of the listener when certain short sound patterns (melodic patterns or rhythmic patterns) are repeated. Similarly, in the context of this essay, by visual “layers” I mean the layers that form in the mind of the audience, not the hundreds of images that the visual artist builds up in the computer.

Previously, I characterized video art as an art form that includes elements of both music and film, an art form in which musical polyphony and filmic linearity are intermingled. Akira Miyanaga showed talent from the outset in creating video art as “music,” producing a debut work with 100 layers of video in a way similar, in a sense, to a composer writing a symphony score with 100 staves. The next problem the artist confronted was how to add “film”-like reality to video-art-as-“music.” To cultivate the “film”-like aspects of his work, Miyanaga started by cutting down the video that constitutes his material to a single layer of straight video which he looped to produce a single visual layer that was then staggered and layered to create about the lights of land (2010). This is none other than the method used to create minimal music. In addition to the methodology of repetition and staggering, one can also see in early minimal music signs of a conflict similar to the problem Miyanaga confronted.

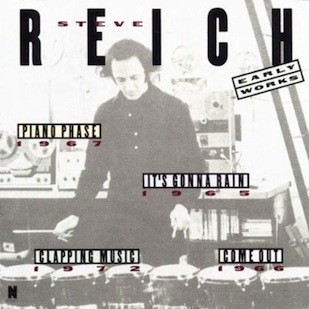

Steve Reich – Early Works.

Steve Reich – Early Works.In “Come Out” (1966), an early composition by Steve Reich, for example, a fragment of a conversation recorded on tape was made into a loop and progressively staggered and layered. The material in question had a political context in that it was a statement by a black youth, suspected of committing a murder during the Harlem Riot of 1964, explaining how he had punctured a bruise and shown the bleeding wound to police to indicate that he, too, had been injured. However, over the course of the 15 minutes during which the loop featuring the words “come out to show them” was repeated and staggered, the words gradually became indistinguishable and lost their meaning, eventually becoming a pulsating reverberation. Even the most touching of words end up as simply noise when they are looped and overlapped. The clash of political truth and musical methodology gave rise to an acute dissonance, giving this work a peculiar air of authenticity.

The same thing could probably be said of video loops. The repetition of a loop produces layers, but by superimposing one on top of another, the actual context and meaning with which the original layer was imbued is destroyed. The actions of staggering and layering loops of live-action video destroy the reality of the “live-action.” In other words, about the lights of land failed as a complete response to the problem outlined above. The following works, arc and scales, represented two different approaches to this same problem.

Still from scales (2011), HD video, triple projection, 9 min 38 sec. Courtesy the artist and Kodama Gallery.

Still from scales (2011), HD video, triple projection, 9 min 38 sec. Courtesy the artist and Kodama Gallery.Scales consists of a number of straight videos that are clearly discernable (although they are only just discernable as live-action videos, and make no reference to any real context in particular), rendered as loops with different frequencies and layered. It is clear that the intention was to generate “music”-like polyphony by layering layers with “film”-like linearity in accordance with different rhythms. One could probably compare this to the decorative pieces in the form of layered collages Reich composed in the 1970s and beyond, for he used as his material not sound sources with specific meaning but purely instrumental patterns, which he repeated and layered at varying frequencies. In other words, by using video material he shot himself in a similar way as patterns, Miyanaga conceived of a work that continues to metamorphose in the context of a “music”-like process without the “film”-like video losing any of its filmic characteristics.

Unlike sound patterns, however, all live-action videos are vestiges of the inherent reality concerned, and cannot be recycled as simple abstract layers. This is why when such videos are collaged, a dissonance usually arises, and in fact if such a dissonance does not arise, then the videos in question do not deserve to be called live-action videos. In scales, however, there is no such dissonance. Perhaps this is the reason for this work’s pre-established harmony-like monotony and the sense of déjà vu it elicits, like background video.

Still from arc (2011), HD video, triple projection, 7 min. 30 sec. Courtesy the artist and Kodama Gallery.

Still from arc (2011), HD video, triple projection, 7 min. 30 sec. Courtesy the artist and Kodama Gallery.To what extent can “film”-like realism be incorporated into “music”? With arc, Miyanaga presents yet another attempt to answer this question. The relentless video collage (consisting of gradual transitions between and the overlapping of footage of the Swedish seacoast in summer, footage of the regions struck by the Tohoku tsunami, footage of the sun, clouds and water, and footage shot from a moving train) has the effect of absorbing the audience in the screen. At this point, “film”-like realism is added not in the form of the context of the reality that was videoed (the destruction caused by the tsunami, for example), but in the form of the theatrical dissimilation of interrupting this absorption. On the one hand the artist induces absorption by further refining the video collage technique he developed in Wondjina and about the lights of land. But on the other he boldly introduces elements that bring about a sense of dissimilation, distance and disharmony, such as the movement of the handheld camera, the horizon that stretches as far as the eye can see, and the repetition of kitsch buildings and images, successfully counteracting the “music”-like absorption with “film”-like theatricality.

While it could be said to be fresh in that it employs bold composition and disharmony hitherto unseen in Miyanaga’s work, overall arc is so short (it is unlikely to bore audiences) it is at risk of being seen as timorous, and leaves insufficient room for development. As with scales, it might best be described as an exercise by Miyanaga, an artist whose work is in transition. As well, the installation-like approach to the screening of Miyanaga’s work at the likes of Kodama and αM galleries in Tokyo strikes me as an unnecessary commercial blandishment. I would rather it were edited to lengthen it by around half as much again and presented simply on a screen with a single bench for the audience.

Akira Miyanaga’s “scales” was on display at Kodama Gallery, Kyoto from January 14 to February 11, 2012.

-

Layering occurs when a single pattern is repeated by the first instrument, and the music is built up by gradually adding different instruments while staggering the same layer or creating new layers from sections of that layer. The piano, percussion instruments, clarinet and vocals begin to change places in depth with one another, and a process is set up in which every part of the piece takes its turn at occupying every place, whether real or imagined based on the layering of sounds, in it. “The strips, the lettering, the charcoaled lines and the white paper begin to change places in depth with one another, and a process is set up in which every part of the picture takes its turn at occupying every plane, whether real or imagined, in it.” [Clement Greenberg, “The Pasted-Paper Revolution,” in The Collected Essays and Criticism, vol. 4, (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1993), 63.] Minimal music is the collaging of layers.