THE RINGS OF SATURN

By Andrew Maerkle

Janet Cardiff & George Bures Miller – Experiment in F# Minor (2013), mixed-media interactive sound installation including 72 loudspeakers on two wooden worktables, 2.44 m x 1.83 m. Installation view, Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto, 2013. All images: © Janet Cardiff & George Bures Miller, courtesy Gallery Koyanagi, Tokyo.

Janet Cardiff & George Bures Miller – Experiment in F# Minor (2013), mixed-media interactive sound installation including 72 loudspeakers on two wooden worktables, 2.44 m x 1.83 m. Installation view, Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto, 2013. All images: © Janet Cardiff & George Bures Miller, courtesy Gallery Koyanagi, Tokyo.Based between Berlin and Grindrod, British Columbia, Janet Cardiff and George Bures Miller are known for their multidimensional approach to working with sound. In addition to exploring the spatial, dynamic and psychoactive potential of the recorded voice, music and field recording, their works variously incorporate aspects of cinema, literature, history, video, kinetic sculpture, installation, interactive technology and natural and constructed landscapes to create immersive worlds and situations. Having exhibited widely across the world, they represented their native Canada at the 49th Venice Biennale in 2001. Their work is currently on view in concurrent exhibitions in Japan. In a solo exhibition at Gallery Koyanagi, Tokyo, through October 19, they are presenting the interactive music installation Experiment in F# Minor (2013), while The Forty Part Motet (2001) is on view in the Aichi Triennale, continuing through October 27.

Interview:

ART iT: To begin with, one word you’ve previously used in discussing your works, particularly in regard to the relationship of works like The Paradise Institute (2001) to cinema, is “spectacle.” How do you conceive your notion of spectacle compared to shock-and-awe spectacle directed at mass audiences?

JC: I guess if you had to generalize our work, it would be in the genre of how people experience cinema, because you go to the cinema to be transformed, or taken over, taken on a journey: you enter and forget about the outside. A lot of our work creates that kind of experience, and we use a lot of the tropes of cinema.

GBM: I’m not sure what you mean by spectacle.

JC: Say with Forest (for a thousand years) (2012) at documenta 13 in Kassel. It’s a big surround-sound piece with something like 25 speakers installed in a forest. Because of the way we use audio, you hear horses running, then soldiers, bombs landing all around, and I think that’s very spectacular. It takes people out of their minds and into the experience, and I think that’s what spectacle is about. But there’s such a variety of spectacle, from the wrestling genre in the US to carnival grounds. We’ve also related other works to the idea of an amusement ride.

GBM: Every piece is different, but as Janet said the most common, consistent thing we like to work with is the idea of immersion. I don’t know how that relates to “spectacle” – sometimes it does, and sometimes it doesn’t. With Forest, because of the surround-sound system you’re not always aware what’s recorded sound and what’s natural.

JC: I think we work in a similar language to the ideas of spectacle in our culture, like big fireworks or the rides at fairs or Halloween shows. We’re working in a pop culture way that uses contemporary technology like the Walkman, or the speakers, or audio systems, but we start with a language the public understands and then shift it so that we can work on conceptual ideas of physicality, sound, space, what’s real and what’s fictional: what is reality and how do we know reality through phenomena? How do we really know it? It’s through our senses. So we play on that sort of thing, whereas in the pop culture world they use spectacle only for awe.

Top: Janet Cardiff & George Bures Miller – The Paradise Institute (2001), mixed-media/multimedia installation, 5.1 m x 11 m x 3 m, 13 min. Interior view. Photo Markus Tretter. Bottom: Janet Cardiff & George Bures Miller – The Murder of Crows (2008), mixed-media sound installation, dimensions variable, 30 min. Installation view at Nationalgalerie im Hamburger Bahnhof, Berlin, 2009. Photo Roman März.

Top: Janet Cardiff & George Bures Miller – The Paradise Institute (2001), mixed-media/multimedia installation, 5.1 m x 11 m x 3 m, 13 min. Interior view. Photo Markus Tretter. Bottom: Janet Cardiff & George Bures Miller – The Murder of Crows (2008), mixed-media sound installation, dimensions variable, 30 min. Installation view at Nationalgalerie im Hamburger Bahnhof, Berlin, 2009. Photo Roman März.ART iT: In The Murder of Crows (2008) you use the Russian march music, which is spectacular, but it also seems you’re using it in a critical or reflective way.

GBM: Maybe. Or maybe we’re just using it because it puts goose bumps up and down your back when those guys come marching into the room.

JC: I think by the way we juxtapose it with other things in that piece, you get a sense of how they fit into the idea of “war is glory.” So it becomes critical when you then have an opera singer singing in reference to the Iraq War, “Where is my leg? […] It was blown off by a bomb!”

GBM: But often we juxtapose things because it’s interesting sounding. We were at the end of a part of the piece we called the “Bad Foot March,” and we didn’t want to end the sound there. Then we remembered being in Nepal and experiencing this wedding march, where at the front of the march there was a traditional Hindu band playing traditional Hindu instruments, while at the back, about 50 meters behind, there was a brass marching band. Halfway in between you had the two mixing together in this crazy cacophony of traditional Hindu music and Western music, and in the middle were the bride and groom.

So we wanted to have that kind of feeling in the transition from the “Bad Foot March” to the Russians. The Russian song is called “The Sacred War,” and it is quite moving, actually. It was a propaganda piece to motivate the troops to fight the fascists during World War II, but really we were just searching for something that worked sound-wise.

JC: Yes, but sounds always carry meaning.

GBM: Absolutely. I’m just saying that we’re not always thinking about the way one thing will fit with another thematically, but we are always thinking how it will fit sonically, and sometimes there’s a happy coincidence that everything clicks.

JC: But with the language for the opera section we wrote the words ourselves. It was inspired by a newspaper story about a father who came home to find his house bombed and the arms of his daughters hanging from the chandelier. That was the basis for the whole piece, and then in one section we turned it into this black comedy with these opera singers, “It was blown off by a bomb!” which makes you kind of laugh but at the same time delivers the message about bombs and war affecting people personally. We told the composer, we want something like “Bohemian Rhapsody.”

So with our work we definitely want to create an emotional response, but also you can’t just throw out all the emotional stuff at once because people turn off, so you bring in other genres, like comedy, or you bring in the dream section, which takes you into another space. I see it as all these different conceptual spaces that you enter when you listen to the different sections. Then when we showed Murder of Crows for the first time in Berlin, where there’s a strong Russian population, the Russian choir meant something completely different from when we showed it in New York.

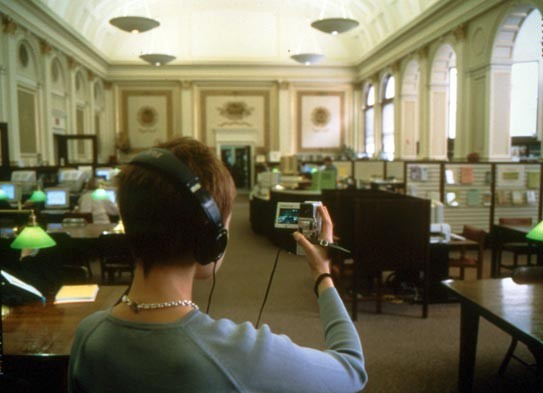

Top: Janet Cardiff – In Real Time (1999), video walk, 18 min. Curated by Madeleine Grynsztejn for the 53rd Carnegie International at Carnegie Library. Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh. Bottom: Janet Cardiff – The Telephone Call (2001), video walk, 15 min, 20 sec. Curated by John S Weber with Aaron Betsky, Janet Bishop, Kathleen Forde, Adrienne Gagnon, and Benjamin Weil for the group exhibition, “010101: Art in Technological Times,” San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, San Francisco.

Top: Janet Cardiff – In Real Time (1999), video walk, 18 min. Curated by Madeleine Grynsztejn for the 53rd Carnegie International at Carnegie Library. Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh. Bottom: Janet Cardiff – The Telephone Call (2001), video walk, 15 min, 20 sec. Curated by John S Weber with Aaron Betsky, Janet Bishop, Kathleen Forde, Adrienne Gagnon, and Benjamin Weil for the group exhibition, “010101: Art in Technological Times,” San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, San Francisco.ART iT: And yet at the same time that you’re doing immersion, you also pull apart the immersion experience by adding background noise or distractions, as in Paradise Institute.

GBM: We like to play with all those layers. We do so many genres of work. The audio walks pull reality apart and play with it, and the video walks, too, even though they’re completely different. They just blow your mind in a way.

JC: When you’re immersed in a video walk, you start believing that the screen is your reality, and then you want the people around you to conform to that reality, and it bothers you that they aren’t lining up with the people inside the screen, so then your head goes into a different space.

The video walks raise so many different questions for us, because we just play. We respond to things and respond to sounds and then go, Oh, that’s really interesting. And then after that we go, Oh, it’s interesting how it talks to us about our relationship to media and how the world now is completely immersed into iPods and iPhones.

So you can make an artwork that plays with that on many different levels. In the Alter Bahnhof Video Walk (2012) for documenta 13, which used iPods, at one point we slow it down, then we speed it up, we rewind, and at another point we say that the battery died, but you can still hear the voice, so you question what reality you’re in.

GBM: A lot of people took the iPods back. We put the “low battery” prompt up on the screen, and then Janet says, “Oh, my battery’s getting low, so I have to change the battery.” We made the screen go black, but you still heard Janet talking on top of that, so obviously the battery wasn’t dead, but some people just turned the iPod off, took it back and said the battery’s dead. They couldn’t cross over into the recognition that it’s just part of the piece. So we love to play with that idea of what we call pulling the rug out from people, and also from the piece itself in a certain way.

JC: Whenever we make a walk we always finish the edit and have a few people test it to make sure they can find their way and everything like that. But when we did our first video walk, In Real Time (1999) for the Carnegie International, what we found was that writers and curators especially could not follow the video. The camera would be going up the stairs on the left, and some of these people were going up the right, so we had to add my voice saying, “Go to the left.” Now we’ve found that people are past that because they’re so used to recording videos on their mobile phones. Everybody’s used to recording reality and understanding how to move with the camera.

ART iT: So after shifting from handheld video cameras to iPods, maybe next you’ll try the Google Glass.

GBM: That would be super cool. I hope Google will give us one.

JC: I’m sure many artists will want to work with it. It’s interesting how you have to make the right work at the right time, otherwise people can’t enter into it. I made the first audio walk in 1991, and I think people listening to it weren’t quite sure whether it was even art.

GBM: It wasn’t all that well done, though, I have to say.

JC: I worked on my own on that one. It was done on a four-track Tascam cassette deck.

GBM: The tools were primitive. For us the boom in audio on computers has been really fortunate. The first audio walk we really did, in 1996 for the Louisiana Museum, Louisiana Walk, coincided with being able to edit on a computer that you could carry in your luggage, although it would crash every 30 minutes.

The video walks we created 15 years ago – that was the perfect moment for them in a way. Now other people are going to steal the idea and start making stuff with it because you have these devices you can carry anywhere. Video is such a powerful thing. We don’t even use it to its full Hollywood potential. In fact, when we did The Telephone Call (2001) at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, a Hollywood guy said he wanted to do a zombie film version of a video walk. But after doing enough video walks we realize there are problems with trying to translate them into big budget. Also, you can’t do them outside because it’s too bright, so you have to limit your location to places where you can see the screen really well.

We’re planning an evening walk as our next project actually, so maybe a zombie evening walk would be pretty cool. It would be terrifying, too. We use binaural audio in the walks, so it would sound like someone was coming up right behind you.

JC: But also what you’re talking about relates to the ghost walks that they have in cities like Sydney and London. So it relates to that whole genre as well.

Janet Cardiff – Villa Medici Walk (1998), audio walk, 16 min, 22 sec. Curated by Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev, Hans Ulrich Obrist and Laurence Bossé for the group exhibition “La Ville, le Jardin, la Mémoire,” Académie de France. Villa Medici, Rome, Italy.

Janet Cardiff – Villa Medici Walk (1998), audio walk, 16 min, 22 sec. Curated by Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev, Hans Ulrich Obrist and Laurence Bossé for the group exhibition “La Ville, le Jardin, la Mémoire,” Académie de France. Villa Medici, Rome, Italy.ART iT: Actually, there’s something very haunting about your walks. In a way they are literally about haunting, like in The Münster Walk (1997) and the Villa Medici Walk (1998), but also in the broader sense that you’re experiencing multiple registers of reality and time all at once.

GBM: Not enough people saw the Villa Medici piece, it was a cool piece.

JC: It went into the souterrains. It was really spooky.

GBM: You ended up in this underground room with big carved heads. In that one we were using Walkmans with cassettes, and of course with a Walkman when the battery dies the playback starts to slow down, so we intentionally made the playback slow down, and people thought the batteries were dying – you would hear Janet’s voice going, “Rorrrrr, roorrr.”

JC: Now it wouldn’t work, because with digital when the battery dies, it just dies.

GBM: We also used the idea of recording things on a cassette recorder, with the “rewind” sound.

JC: People still understand that language, but they understand it now as a retro thing.

Janet Cardiff & George Bures Miller: The Rings of Saturn