TIME TRAVELER

By Andrew Maerkle

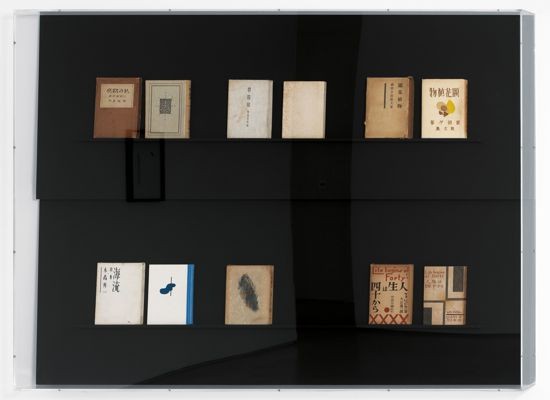

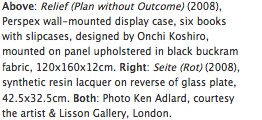

Modernology (Triangular Atelier) (2007), Installation with wall system, 8 rear-glass paintings, partition wallsupholstered in black buckram fabric, joined by metal hinges, dimensions variable. Installation view at documenta 12, Kassel, 2007. Photo Hannes Böck, courtesy Florian Pumhösl and Galerie Buchholz Berlin/Köln.

Modernology (Triangular Atelier) (2007), Installation with wall system, 8 rear-glass paintings, partition wallsupholstered in black buckram fabric, joined by metal hinges, dimensions variable. Installation view at documenta 12, Kassel, 2007. Photo Hannes Böck, courtesy Florian Pumhösl and Galerie Buchholz Berlin/Köln.Based in Vienna, Florian Pumhösl examines the ruptures in the historical narrative of modernism, identifying discontinuities that shed light on our current conditions for art, or discovering latent connections between the past and present. He works in a variety of media, from making highly reduced paintings on plaster supports using the cliché stamping process, to spatial configurations and films like Lac Mantasoa (2000), exploring the inundated ruins of a 19th-century industrial complex in Madagascar.

Pumhösl was recently in Tokyo for a two-person exhibition at Taka Ishii Gallery with Silke Otto-Knapp, entitled “Ratio of distance” (Nov 22-Dec 20). Conceived as an exhibition in parallel, the show featured Pumhösl’s abstractions derived from nautical maps and Otto-Knapp’s paintings based on the landscape around Fogo Island, Newfoundland. But Pumhösl will also be returning to Japan next year for the inaugural Parasophia: Kyoto International Festival of Contemporary Culture 2015, where he will present a new body of work, reflecting on the 1920s and ’30s avant-garde in Japan, based on research into the collections of numerous Japanese institutions.

In anticipation of his participation in Parasophia 2015, ART iT met with Pumhösl before the opening of the exhibition at Taka Ishii to learn more about his practice and his interest in the development of an early global discourse on contemporary art. See also: Silke Otto-Knapp: Cold Dark Deep and Absolutely Clear | Parasophia: Kyoto International Festival of Contemporary Culture 2015

Interview:

Installation view of Silke Otto-Knapp & Florian Pumhösl, “Ratio of distance,” at Taka Ishii Gallery, Tokyo, 2014. Photo Kenji Takahashi, courtesy the artist and Taka Ishii Gallery, Tokyo.

Installation view of Silke Otto-Knapp & Florian Pumhösl, “Ratio of distance,” at Taka Ishii Gallery, Tokyo, 2014. Photo Kenji Takahashi, courtesy the artist and Taka Ishii Gallery, Tokyo.ART iT: You’re known for making works that explore the legacy of modernism, and the dynamics between abstraction, representation and functional design. Can you talk about how you arrived at this practice?

FP: In relation to abstract visual vocabulary, I see myself as a speaker of the language. My generation of artists necessarily approached the historical legacy of modernism from a post-modern viewpoint, a sense of before and after, but at some point it became unsatisfactory for me to be stuck within the limitations of reference resulting from this, of “making art about.” In my current practice, I try to start from experiences, artworks, and constellations within early modernism that qualify for me as possible points of origin for a work in the present.

ART iT: Over the course of your practice have you reconsidered the position of being post-modern? Do you have any sense that we are in fact still within an ongoing period of modernism?

FP: I think in the arts we have never been post-modern in an absolute sense. We are not post-photographic, because there is still work being made that acts within the photographic culture from the past two centuries. Nor have we overcome film. I think what can be said is that there are numerous cultures that relate to modernism which exist at the same time in an unsynchronized way. When I started studying art, in the early 1990s, there was a big sense of disappointment toward modernist art and architecture, which was already at least a generation old. But I would say this has never been a question of deciding either for or against, as modernism is also an unprecise term – maybe nothing one can decide for. I do think one has to accept that numerous cultures departing from modernism exist in parallel, and what interests me is how I can still specify within this situation – and realize works under present conditions.

ART iT: You’ve done a number of works that look at Japanese avant-garde art and design from the 1920s and ’30s – in particular figures like Tomoyoshi Murayama and Koshiro Onchi – and have also referenced the ethnographer and architect Wajiro Kon’s concept of “modernology,” which similarly dates to that period. What is it that drew you to Japan as a site of investigation?

FP: I can only speak subjectively on this point. I think what got me started were examples of 1920s and ’30s book design. What struck me was that the visual language seemed to be transferred and transformed in a way that clearly suggested an early model of a global discourse. The Eurocentric interpretation would be to say that modernism was implanted mainly from the centers, but we have learned in the art historical debate concerning non-Western modern cultures that it encountered important intersections as soon as it started to spread. The case of Japan is intriguing because the visuality was shaped and radicalized through transformation and translation. Especially in book culture, one can observe that behind the actual communicative function there is a very distinct proto-minimal graphic language.

ART iT: Certainly with Japan, more than the artworks that were made at the time – relatively few of which survive today – the graphic design and texts powerfully communicate the degree of simultaneity and interaction shared by the local avant-garde with a global discourse, as well as how local sensibilities were used to further innovate the global visual language.

FP: Absolutely. That makes it even more intriguing. I think the way new and old media were defined in this scenario reorganized the whole notion of functionality. When it comes to the abstract image, I think there were a lot of transformations taking place in which the artists were redefining the space and direction of the book, in relation to new orders of reproducability. So when it comes to abstraction, I would not always only put Western painting in the center.

ART iT: Currently there is a big push from Western institutions such as MoMA and the Tate Modern to collect different modernisms outside the Euro-American canon, and one concern is that this could co-opt independent narratives back into the dominant narrative. Do you see your interest in Japanese or other modernisms as a supplement to the Euro-American canon, or as a way to subvert that canon?

FP: I think I’m primarily taking an artistic perspective here, in the sense that I have to accept the differences between museum culture, curatorial and artistic practice. The questions you address are complex. There is not much wrong about the integration of non-Western avant-garde work into the canon of the museum. I recently went to the Centre Pompidou, and was more than happy to see works there by artists like Tarsila do Amaral and Joaquin Torres-Garcia.

On a contemporary curatorial level, one of the questions I see is the discrepancy between the international as we desire it and the global as we constantly produce it. The more historical distance there is, the easier it seems to classify.

ART iT: Of course, a number of your works – such as the Modernology (2007) installation that you presented at documenta 12, and the “Cliché” paintings, or even the works here – reduce preexisting visual samples down to their most basic elements, and decontextualize the source material through this process. How do you understand the relationship between the source material and the resulting work?

FP: It depends. In this exhibition, I have a motif in a very classical sense – the navigational map – and I try to make a picture of it. What happens if you debate its functionality, or conversely, what happens if you take away the expectation that you have for an abstract composition? Those are the possibilities that abstraction provides: that I can negotiate the spectrum between certain expectations that are projected toward an image. As I said, I see myself as a speaker of the language, and the language gives me a tool to describe the dynamics between meaning, expectation and visuality, as opposed to focusing on a style or stylistic method. There are previous works where I have a historical point of departure, like Rodchenko’s painting Expressive Rhythm (1943), for a film installation I made in 2010, or the dialogue between my paintings and Koshiro Onchi’s book designs. But I do not always have a concrete source.

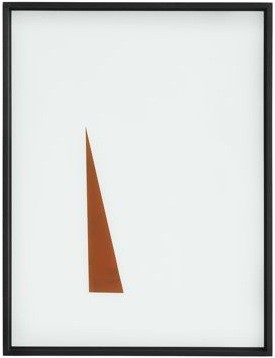

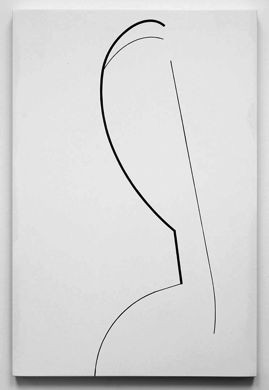

Left: BlauesRaster (2014), oil on ceramide plaster, 36.6 x 25.5 cm. Right: Expanse 5 (2014), oil on ceramide plaster, 40.2 x 26.9 cm. Both: Courtesy the artist and Taka Ishii Gallery, Tokyo.

ART iT: With the works here, for example, on my first viewing they reminded me of printer’s marks. But then thinking of them as sea lanes in relation to Silke’s paintings of islands, they began to evoke the actual oceans people are traversing, the experience of which is of course completely different from the abstracted representation. There is a tension between nature or actuality versus abstraction and mapping in the work.

FP: A map is not entirely abstract. A map is instructional, and at the same time descriptive, so it is not an abstract picture. But it uses abstraction as a method, and it gives a lot of room to play with certain expectations that you would have for a sign or possible meanings you would address through the image. In the case here, for example, that space can be entered through a detail. A route would circumscribe a landmass (which is never shown) and it does that simply through instructional, or perhaps temporal objects – the printed lines on the plaster paintings.

ART iT: How do you arrive at the final forms when you’re working with something like an actual map?

FP: I would say it’s a semi-intuitive process in which I isolate and contextualize my motif until it seems to be in the right place. I spend a lot of time trying to find out why a picture interests me, and I go through an extensive process of drawing to interpret my visual material.

ART iT: Do you have the sense that each body of work builds upon the next? Are you creating your own language?

FP: The main catalyst for me is aesthetic experience. It’s not linear. I wish there was always something leftover that I could cook the next stew from. This series, for example, returns to a picture I made nine years ago of a military maneuver of a ship. The Dutch art historian Eric de Bruyn wrote about this work, and I thought it would be interesting to try investing more in this question of planar depiction and nautical space. When I saw Silke’s island paintings in her show at the Camden Arts Centre earlier this year, all of a sudden it seemed to make more sense.

Expressive Rhythm (2010/2011), single-channel film projection, 35mm film, color, 28 min looped, sound, site-specific. Projection: front projection, approx 480 cm total length. Production MUMOK – Museum Moderner Kunst Stiftung Ludwig Wien, Vienna. Installation view in the exhibition “678” at MUMOK, 2011. Photo Hannes Böck, courtesy the artist, Galerie Buchholz Berlin/Köln, Krobath Vienna/Berlin, and Lisson Gallery, London.

Expressive Rhythm (2010/2011), single-channel film projection, 35mm film, color, 28 min looped, sound, site-specific. Projection: front projection, approx 480 cm total length. Production MUMOK – Museum Moderner Kunst Stiftung Ludwig Wien, Vienna. Installation view in the exhibition “678” at MUMOK, 2011. Photo Hannes Böck, courtesy the artist, Galerie Buchholz Berlin/Köln, Krobath Vienna/Berlin, and Lisson Gallery, London.ART iT: You mentioned the idea of a “temporal object.” How does time function in the work? For example, you have the “Cliché” works combining a large version, medium version and small version of the same motif, suggestive almost of a montage sequence – although obviously I am looking through an online image as opposed to being there in person.

FP: Where is the picture? I think it’s permanently shifting between physical and imaginary space. The imaginary space of the picture fundamentally changed after the arrival of time-based media. Hans Richter called it the “filmic picture of construction.” The object of abstraction is from its very origins a temporal thing.

ART iT: Do you feel it’s still necessary to make a distinction between modernism and the avant-garde today? I suppose the stereotypical image is that modernism is more cerebral while the avant-garde is anarchic.

FP: For me, the term avant-garde is linked to biographies, and to the work and personal relationships between artists and their debates – people who dedicated their lives to something daring and far from the mainstream. I think, for example, Onchi and Murayama are two instances where these terms – the more epochal modernism, and the more active avant-garde – could be exemplified. On the one hand, Onchi addresses or reflects upon methodological possibilities, and implements them without much political intent, while on the other you have Murayama, the adventurous artist, with his revolutionary persona. Hard to compare, but both succeded in their own ways.

Return to Index

Forecast 2015: Florian Pumhösl