Chaos, Destruction, Recurring Chaosmos – Beyond the ‘Hametsu*Lounge’

Installation view of “Hametsu*Lounge” (2010) at Nanzuka Agenda Shibuya. Courtesy Nanzuka Underground.

Installation view of “Hametsu*Lounge” (2010) at Nanzuka Agenda Shibuya. Courtesy Nanzuka Underground.Following on from my review of the recent “Chaos*Lounge” exhibition at Takahashi Collection Hibiya in Part 6 of this series, I published an essay on the “Hametsu*Lounge” exhibition at Nanzuka Agenda Shibuya in The Shincho Monthly (August 2010). In place of the orderly “exhibition” by the pixiv-orientated Chaos*Lounge members on display in Hibiya, “Hametsu*Lounge” was an attempt to present – as is – the confusion that arises of its own accord from the living circumstances of so-called “geeks,” people who specialize in computer programming on a professional level and who normally have no connection whatsoever to art, by having them inhabit the space concerned. The initial plan for “Hametsu*Lounge” called for an intervention mid-way through the exhibition period by “Chaos*Lounge members,” as artists, to quell this confusion and bring about the “rebirth” of the event as an exhibition before it came to a close (“Rebirth*Lounge”). However, this rebirth was unsuccessful, and confusion still reigned when the exhibition ended. My essay sought to offer a different perspective on the trends that emerged at “Chaos*Lounge” – an exhibition that has been seen solely in terms of the fascination of “novelty” – by singling out the invisible forms of net architecture that unfold in a non-ideological fashion and exploring these for the oblivion and repetition peculiar to “bad places.” There are those who would take this simply as “criticism,” but this was by no means the case. If we were to discuss the “novelty” of “Chaos*Lounge” solely in terms of the substance of the images of pixiv-like drawings and anime characters that flood the Internet, then sooner or later “Chaos*Lounge” would very rapidly become dated on account of this “novelty.” But is the problem really the “display” (representation) of the visible in the form of these characters? In fact, unless one looks at the invisible formal repetition that should be in the background, then ultimately “Chaos*Lounge” can only be discussed in terms of representational images. To this extent, any reconciliation with the context of Japanese art since the modern era would be difficult. In my Shincho article, in order to achieve such reconciliation, I conditionally enclosed this superficial novelty in parentheses and attempted to verify not the possibilities for the future but the formal repetition of the Japanese avant-garde of the past by comparing it with the anti-art of the 1960s and beyond.

Installation view of “Hametsu*Lounge” (2010) at Nanzuka Agenda Shibuya. Courtesy Nanzuka Underground.

Installation view of “Hametsu*Lounge” (2010) at Nanzuka Agenda Shibuya. Courtesy Nanzuka Underground.Although I barely touched on it in my “Hametsu*Lounge” essay, Arata Isozaki’s “The Mirage City – Another Utopia” exhibition, which was held in 1997 to coincide with the opening of the NTT InterCommunication Center (ICC) in Nishi-Shinjuku, is a possible reference point for the themes I wanted to explore. However, I instead focused on Isozaki’s “Joint Core System” project, exhibited in 1962 at the Seibu Ikebukuro group exhibition “Mirai no toshi to seikatsu” (Cities and Lifestyles of the Future) to highlight the synchronicity/repetition between 2010, when “Chaos*Lounge” took place, and the 1960s. However, to the extent that it sought to create an artificial island in the South China Sea off the coast of Macau as “another Utopia” and invited multiple others to participate in a city-planning project for the island in the hope of creating a virtual city in which absolute authority was not confined to any one individual, 1997’s “The Mirage City” was in fact also a repetition of 1962’s “Joint Core System.” Furthermore, it is not unthinkable that by opening up participation in this project to the Internet (which was still very much in development at the time), the organizers were attempting to substitute the information environment of the 1990s and beyond for the setting of “Joint Core System” in the 1960s (in which aerial photographs of central Tokyo were stuck to a table and visitors invited to offer ideas on any kind of infrastructure they liked by hammering in nails and stretching colored wire across the table at will).

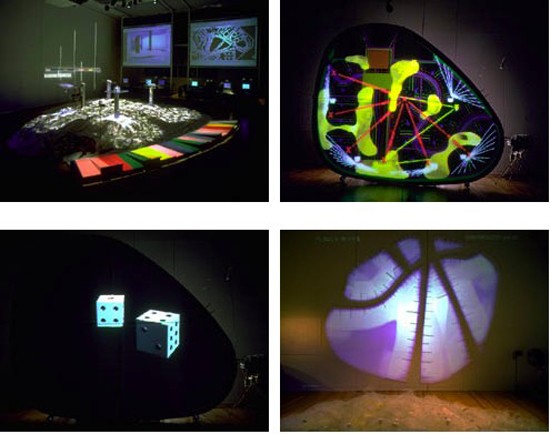

Installation views of “The Mirage City – Another Utopia” (1997) at NTT InterCommunication Center [ICC].

Installation views of “The Mirage City – Another Utopia” (1997) at NTT InterCommunication Center [ICC].Incidentally, the artificial island proposal for 1997’s “The Mirage City” was divided into four patterns: Prototype, Signatures, Visitors and Internet. With the prototype plan prepared for the Japan Pavilion at the 1996 Venice Architecture Biennale as “Prototype” and the division and integration of the artificial island by 48 architects based on an urban plan for Rome left behind by Piranesi as “Signatures,” it was possible to maintain a certain order. But “Visitors,” which adopted a format whereby 12 artists, architects and critics (including two groups) dubbed “digital architects” were invited along and asked to work sequentially (as if composing a traditional renga poem) in developing their own plans based on the prototypes prepared by their predecessors, and “Internet,” in which large numbers of the general public were invited to take part via the Internet, descended into significant disorder.

As with 1962’s “Joint Core System,” while the invited artists and Internet viewers were as a rule granted freedom and equality with respect to expression, these initiatives lacked the “fraternity” necessary to resolve the contradictions between the two into a unity of purpose. Resultantly, those who were supposed to carry on the plans of their predecessors altered them completely, in some cases overturning the very premise of an artificial island surrounded by ocean. As well, with regard to “Internet,” it seemed as if the methodology itself for drawing together the opinions of multiple participants into an urban plan for an artificial island with limited space reached an impasse, leaving visitors who had come to see the results with the impression that the exhibition was a failure (ruined and never to be reborn in such a format).

Installation views of “The Mirage City – Another Utopia” (1997) at NTT InterCommunication Center [ICC].

Installation views of “The Mirage City – Another Utopia” (1997) at NTT InterCommunication Center [ICC].And yet, looking at the incendiary thesis in the form of the words that the supervisor Isozaki himself inscribed on the cover of the exhibition catalogue – “Eliminate and leave everything up to auto-generation! Annihilate the , cover it with mesh!” – one is reminded once again of just how important it was at this exhibition to in fact present a system that would never lead to “success equaling unity of purpose.” At “Joint Core System” in 1962, multiple other participants (visitors) expressed their views on the futuristic city plan on an equal footing with the architect; so the table set up by Isozaki ended up with nails and wires stretched over it randomly, and ultimately fell into ruins. And when it was all over, Isozaki signaled not the “completion” of this project but its “burial under ashes,” pouring plaster of Paris over this “urban plan for the future.” On the other hand, while “The Mirage City” could be said to have been a project in virtual reality, the documentation of its disorder remained on the Internet even after the end of the exhibition, recapitulated as the remains of the virtual futuristic city buried under plaster of Paris in 1962, later sinking into oblivion.

In the case of “Hametsu*Lounge,” although it was certainly novel as art in the sense of the wholesale introduction of each database for the character format, from the standpoint of the elimination of telos and the annihilation of the center, both of which were repeated in 1962’s “Joint Core System” and 1997’s “The Mirage City,” and of the “disordered mesh [ie, chaos] blanketing the space” that emerged as a result, the same format is still repeated. In fact, because “Chaos*Lounge” reached an impasse with its rebirth at Nanzuka Agenda, perhaps one should say it unconsciously recreated – and to this extent “reproduced” – the “destruction” of 1962 and (especially) the doubled (analog and digital) “destruction” of 1997.

This being the case, the problem becomes one of whether “Chaos*Lounge” can be “reborn” in the true sense of the word after the “destruction” at Nanzuka Agenda (judging by the display at Tokyo Wonder Site Hongo, where there was too much of an emphasis on formal retroactivity, this hasn’t been achieved). This depends entirely on the extent to which the organizers can reorganize, as the kind of “evil imagination” peculiar to places without history, the “chaos without rebirth” that could lead them to real destruction (and I don’t mean at the level of moe kyara endlessly flooding actual space and cyber space via paper and the Internet) and formalize it as “chaos that doesn’t lead to destruction, ie, chaosmos.”