‘Chaos*Lounge 2010’ – Budding freedom/equality and their future

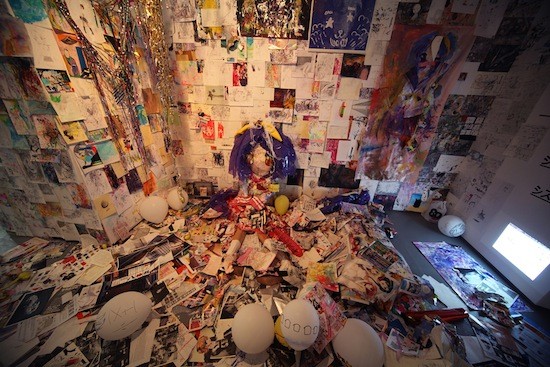

Installation view of “Chaos*Lounge 2010 in Takahashi Collection Hibiya”

Installation view of “Chaos*Lounge 2010 in Takahashi Collection Hibiya”On April 16, artist and art critic Yohei Kurose gave a lecture in conjunction with Takashi Murakami’s GEISAI University (at the Kakai Kiki Gallery). In this lecture, Kurose briefly explained the background and concept behind the exhibition “Chaos*Lounge 2010” (at the Takahashi Collection Hibiya and thereafter various other venues), which he himself curated. The participants then moved on to an “after-school” debate that continued until the small hours. The entire proceedings were streamed live on Ustream, with a virtual audience of over 2000 people gazing anxiously at their computer screens as the “event” unfolded. We await an official response to the outcomes in the form of a promised reorganization of the exhibition. Here I will limit myself to a critical review of Kurose’s lecture.

The origins of “Chaos*Lounge” lie in the efforts of the exhibition’s co-curator Uso Fujishiro in curating off-line artists selected from the online artists’ community pixiv and organizing events including collective art-making sessions in karaoke boxes and group exhibitions in galleries. Kurose’s intervention in his capacity as an art critic resulted in a live painting session on a specially built stage at Takashi Murakami’s GEISAI #14. Tsukasa, the “assemblage” (?) created on that occasion, is among the pieces exhibited at the aforementioned Takahashi Collection Hibiya. The exhibition is an attempt to combine/relativize through the medium of characters the interior (architecture) of the Internet and external space in the form of galleries, and while some have apparently raised doubts as to the degree of finish of the individual works on display, the show should be seen in its entirety, which includes the wealth of non-visual information that proliferates daily in connection with social-networking sites like Twitter and Ustream, without obsessing unnecessarily with the details. It has also been pointed out that the tags on the walls in lieu of captions are not connected to actual links and merely serve as a kind of index for classification purpose, but in fact the works are far more connected to the inextricably invisible Internet – and far more interesting – than the kinds of things the Agency for Cultural Affairs calls “media art” (where interaction is visualized simply as a device of some kind).

Tsukasa wo tsukuro (2010 re-creation), mixed media, 250 x 200 x 100cm

Tsukasa wo tsukuro (2010 re-creation), mixed media, 250 x 200 x 100cm In fact, much is left unsaid, including a detailed explanation of how the artist can intervene again artistically in the results on the Internet, where, on account of the automatic generation arising from the architecture, the traditional concept of the artist is invalidated. For this reason, I looked forward to Kurose commenting on these matters in his GEISAI University lecture, which meant it was all the more surprising when, despite his declaration that “Japanese art didn’t produce anything in the noughties,” he brought up Yoshitomo Nara, whose work could perhaps be described as representative of art in the 2000s. According to Kurose, Nara’s creative approach, as seen in his exhibition “A to Z” (Hirosaki, 2006), of mobilizing large numbers of volunteers is reminiscent of relational art in the sense that it stresses relationships among actual people and cities, for example, but in reality “connections” in virtual space (on the fan site HAPPY HOUR) take precedence, and on the pretext that the results of the crystallization of these “connections” in the form of “stuffed toys” and graf’s “huts” constitute the exhibitions, Kurose attempts to forge an artistic link of sorts between Nara and “Chaos*Lounge.”

However, based on my impressions of what I saw on display at Hibiya, the difference between “Chaos*Lounge” and “A to Z” is clear. Of course I’m referring not to things like scale and budget, but to the fact that it was none other than a sense of solidarity based on fraternity (“Nara love”) that held together the network that materialized at the Nara exhibition in Aomori. At the Hibiya exhibition, on the other hand, although there may have been feelings of moe directed at the character, moe doesn’t function as a symbolic order (ie paternal authority) the way “Nara love” does, and in fact the presence of so many uncontrollable, wayward feelings of moe all originating from separate individuals inevitably gives rise to a kind of rhizome with no center and shoots rapidly branching off in all directions.

Incidentally, Kurose cited Nara’s “huts” as devices that gave visual expression to the networks behind the Nara exhibition, but the fact that these fragile structures full of cracks were able to function effectively can only be put down to the cohesive capabilities of the “Nara love” mentioned above. In contrast, if anything like a hut were provided at “Chaos*Lounge,” it would inevitably be chewed to pieces in an instant on account of the boundless proliferation of kyara-moe, or the affective elements of the character. No doubt it was precisely to prevent such “chewing to pieces” that a style of presentation that could be called conservative was adopted at Hibiya, but if there is an essence to “Chaos*Lounge” it probably lies in the matter-of-fact, even brutal way in which the difference in the capacity of the virtual space provided by Internet architecture and physical spaces like galleries is brought to light. That this is summarized in a way that is not deft but rather “forced” also probably allows room for the power of imagination to mediate between the two. In fact, of the examples presented by Kurose as precedents for “Chaos*Lounge,” those with the most potential were probably Mozoshi off, which saw karaoke boxes hired for the purposes of collective art-making, and live collective art-making initiatives like Gohan*Lounge, which saw attendees at the reception for the Hibiya exhibition meet afterwards at a nearby izakaya and engage in art-making over an unspecified period while drinking and eating, almost as a kind of second party. However, such initiatives mustn’t turn into the kind of unsophisticated live painting sessions once seen at Graffiti. While calling to mind in every respect the likes of Twitter and Ustream and remaining continuously connected to and employing as background architecture the Internet, those involved should actually do their utmost to sustain their activities and remain non-time/place specific over 24 hours within the same physical coordinates.

Mozoshi off (2010)

Mozoshi off (2010) Gohan*Lounge (2010)

Gohan*Lounge (2010)That being the case, perhaps we should be referring as our model not to Yoshitomo Nara’s “A to Z” but rather to the Yomiuri Independent exhibitions that self-destructed in 1963 – or to Arata Isozaki’s Joint Core System (Incubation Process), which was formalized even earlier in 1962. The Independent exhibitions were based on the idea originating from France’s Citizen’s Charter that individuals have the right to act freely, but why in Japan did these exhibitions lead to such a radical self-destruction? To expand upon an argument Kojin Karatani once made, it was because although the concepts of freedom and equality originating from Europe were introduced word for word, the “fraternity” required to sublate in a Kantian sense the contradiction between the two (civil society-style free competition and socialist equality are antagonistic, as seen in the gap between rich and poor, for example) was lacking. In Nara’s “A to Z, too, there was no doubt a contradiction between the freedom and equality of the volunteers, but its destruction was guaranteed by the pseudo-fraternity of “Nara love,” as a result of which it was possible to concentrate on the art.

But what about “Chaos*Lounge”? I would venture to say that the thing that most closely resembles fraternity at “Chaos*Lounge” is probably kyara moe, but (as I mentioned above) this is not symbolic but allegorical, and because there is no center in a rhetorical sense (it’s a succession of dislocations), it fails completely to function as fraternity. So, although “Chaos*Lounge” appears to be supported by a kind of group love, in fact this is incapable of uniting the various exhibits. Rather, it not only transforms the results of the collective art-making “necrophilically” (the corpse in this case being the corpse of Tsukasa), but also seems to lead everything towards destruction.

Uso Fujishiro and POST POPPERS Letters from Chaos*Lounge members (2010)

Uso Fujishiro and POST POPPERS Letters from Chaos*Lounge members (2010)But perhaps this is as it should be. If, as Kurose claims, “Chaos*Lounge” can trace its origins to the kind of “bad” architecture peculiar to Japan produced by the likes of Nico Nico Douga and pixiv, then even if it seems to be imbued with modern ideas in the form of “freedom,” “equality” and “fraternity,” in the final analysis these are not “freedom,” “equality” and “fraternity” (even if they have the appearance of these). This being the case, why not try using “Chaos*Lounge” as a trigger to push to the extreme and expose like never before those aspects of Internet society that still remain in virtual space that have earned it a reputation as a “bad place” by relocating them to physical space in the form of galleries? One could also cause chaos around the clock by taking full advantage of Ustream’s live broadcasting capabilities. The success or failure of this would depend on the ability to find a suitable place of relaxation (ie a lounge as a temporary “sphere/zone”) capable of preventing the kind of unfraternal self-destruction (ie chaos arising from a “bad place”) that dogged the Yomiuri Independent exhibitions in the form of a critical reverberation/echo in response to bad architecture.

“Chaos*Lounge 2010 in Takahashi Collection Hibiya” took place from April 10 to 18.