Interior Homelands: Anish Kapoor in Mumbai and Delhi

By Aveek Sen

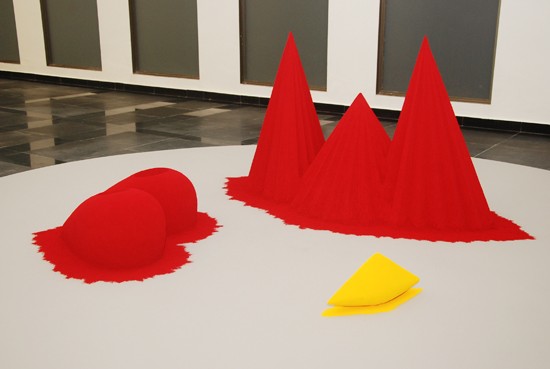

My Red Homeland (2003), wax and oil-based paint, hydraulic motor, steel block. Courtesy Anish Kapoor and Lisson Gallery, London.

My Red Homeland (2003), wax and oil-based paint, hydraulic motor, steel block. Courtesy Anish Kapoor and Lisson Gallery, London.In Italo Calvino’s Cosmicomics, among the little stories about the history of the universe, there is one called “Blood, Sea” that makes me think of Anish Kapoor’s art. In this tale, Calvino links the birth of sexual desire – or, loosely speaking, love – with the evolution of a circulatory system in the cells that are the primordial ancestors of man and woman. As the first living cells swam about in the undifferentiated “sea of our origins,” they craved maximum contact with their liquid environment. This could not be achieved simply by expanding their exterior surface, their “skin.” But those who managed to swell, and then involute into hollow structures of increasing complexity, found themselves at an advantage: the sea could now flow into them and be enclosed within. These sea-filled cavities eventually grew into a system of blood circulation. The outside became the inside. The first, common blood-sea became blood and sea – inside and outside eternally separated and eternally joined by something as tenuous as skin.

The creation of inside and outside not only divided space, but also demarcated body from body, body from space and, eventually, mind from body, mind from mind, and mind from space – forms of division that came with their own possibilities of fleshly or mystical union. So, our “ancient swim through the scarlet depths” becomes part of the body’s memory: “The underwater depths were red like the color we see now only inside our eyelids.” And desire becomes the call of blood to blood, or sea to sea, within and across the boundaries of skin. It is out of this stuff – carnal and cosmic at the same time – that Calvino spins his Tristan-and-Isolde, Antony-and-Cleopatra, Bonnie-and-Clyde fable of blood and sea, love and death: “this story of the risk of blood, of the possibility of our blood returning to a sea of blood, of a false return to a sea of blood which would no longer be blood or sea.” And it is out of this, and similar, stuff that Kapoor has made most of the work we see, for the first time in India, in two current shows in Delhi and Mumbai, the latter being the city where he was born in 1954.

Installation view of To Reflect an Intimate Part of the Red (1981) at National Gallery of Modern Art, New Delhi, 2010-11.

Installation view of To Reflect an Intimate Part of the Red (1981) at National Gallery of Modern Art, New Delhi, 2010-11.In Delhi’s National Gallery of Modern Art, we get into the show, apparently not through sculpture, but through what looks like architecture – the various models, drawings and notes for civic and public-art projects, of what has now become a legendary giganticism achieved at notorious expense. Some of these Kapoor has already realized, but many are yet to be built, if ever. Looking at this part of the Delhi show is a bit like peering into Leonardo’s notebooks of cosmic-mechanical schemes, interspersed with precise, but hermetic, observations (“Be nothing”). But as we move through the little models of subway stations, bridges, domes, columns and landscapes, suspended between the impossible and the achieved, generously or audaciously exceeding their necessary functions, and peopled by tiny human figures that give us the staggering scale of things, a strange set of confusions begins to lead us on, like a master sorcerer, through a different sort of physical/metaphysical labyrinth.

Where are we, and what are we among? In relation to these objects that we are moving around and through, are we very big or very small? Are we inside or outside? If we are inside, then what are we inside of? Are we imaginarily entering and exiting real, constructed spaces, or are we inside somebody else’s body or, more excitingly, mind? Simultaneously, are we also about to rediscover our own insides, to enter – turn into, turn back into – ourselves? (Suggesting both entry and transformation, progress and regress, sculpture and architecture, “into” is a quintessentially Anish Kapoor preposition.) And as we allow these questions and confusions to lead us on, we also find ourselves resisting the allure of these works and of the questions they generate. We pull back physically and cerebrally, gathering together our own doubts and difficulties, hesitating between danger and delight to cross over into spaces – something like the “zones” in Tarkovsky’s Stalker – that are both uncanny and familiar, our own and not our own, deeply known and deeply unknown.

Installation view of Past, Present, Future (2006) at National Gallery of Modern Art, New Delhi, 2010-11.

Installation view of Past, Present, Future (2006) at National Gallery of Modern Art, New Delhi, 2010-11.Suddenly, walking among the models, we are in front of a blank white wall of the NGMA. And high above us, magically turning wall into flesh, building into body, is a livid wound. It is a sharp, simple cut in the white surface, through which we glimpse an interior redness of wood, fiberglass and pigment. Kapoor calls this work of the late 1980s The Healing of St Thomas. The pull, and the resistance, that we were feeling so far towards the spaces opening up or closing in with the models become, in this work, the apostle Thomas’s doubt on hearing from his peers that they had seen the risen Christ. He would believe them after he had seen and touched Christ’s wounds himself. Thomas overcomes his incredulity only when Christ invites him to touch the stigmata: “Reach hither thy hand, and thrust it into my side: and be not faithless, but believing.” For the apostle’s doubt to be healed, Christ’s body must remain wounded and vulnerable to touch. It seems, from St John’s account, that it was enough for Thomas only to have seen the wounds. Thomas had not felt compelled to finger them as well, as Christ would have allowed him to. “Thomas, because thou hast seen me, thou hast believed,” Christ tells him afterwards, “blessed are they that have not seen, and yet have believed.”

In a gallery teeming with security personnel guarding with their lives the artifacts from being touched, the irony of alluding to this biblical story about seeing, touching and believing is wonderfully layered. By placing the wound unreachably high above our heads, yet making it look shockingly real, Kapoor arouses as well as frustrates our desire to touch it, to test its mystery and materiality. And this mix of seducing and resisting engagement, of beckoning us in and shutting us out at the same time, or projecting us into another space that is somewhere beyond the actual surface of the work, is essential to how both the Delhi and the Muumbai shows present themselves physically to us.

The shows court our direct involvement by arousing our curiosity, memory and imagination in ways that are viscerally related to our bodily lives, never letting us lose sight of how our mental and imaginative lives – our inner lives – are embedded in our bodies. And this is done, not cerebrally, but through the immediacy of the work’s material presence, the “bodily recall” of its color, texture, form and imagined feel. Yet, this blood-and-guts intimacy between the viewer and the work takes place in a vast and constantly shifting hall of allusions. This hall is a Wagnerian theatre built out of the larger, and less personal, structures and symbols of philosophy, theology, psychology, history and myth. Inside it, a vital traffic is kept alive between body and spirit, connecting what we see and sense with what we feel, think, remember, question and believe.

Installation view of “Anish Kapoor: Delhi / Mumbai” at Mehboob Film Studios, Mumbai. Photo Mark Prime.

Installation view of “Anish Kapoor: Delhi / Mumbai” at Mehboob Film Studios, Mumbai. Photo Mark Prime.In Mumbai, the immense spaces of the Mehboob Film Studios (where some of Bollywood’s most extravagant films are shot) – so neutral in themselves, yet making up one of the city’s great houses of illusion – become precisely such a theatre. In the steady glare of an austere, white light, we are confronted with a drama of contrasts – material, visual, psychic, metaphysical – that takes us to the heart of how Kapoor creates his spectacles of engagement and disengagement. On the one hand, we have the larger-than-life, variously shaped sculptures of stainless steel polished to an almost inhuman, noli-me-tangere perfection. And on the other hand, along the margins of the space created by the steel pieces, there are two works that use a peculiar substance created out of soft wax, petroleum jelly and red paint that takes us right into the stuff of our bodies. They evoke desire, danger and disgust, but transcend them through a giganticism that takes us beyond the ordinary human scale of things.

Together, these two bodies of work keep up a continual play between fleshly intimacy and steely distance, the carnal and the abstract, which expands and reverberates around us in the grey, empty heights of the studio. The steel pieces work as huge distorting mirrors, mostly concave, which pull us to themselves only to throw us back and project us into spaces that are strangely abstracted from the actual surfaces of the mirrors. So, we are both pulled close, and into, the steeliness of steel and thrown out into a weirdly dematerialized limbo that turns objects into non-objects, space into non-space, and persons into non-persons.

As we move backwards and forwards in front of these mirrors they break us up into crazy fragments and put us together again, or suddenly make us disappear completely and become nothing. And because we are not allowed to touch them, we never know for sure, as we stand close to what appears to be a concavity, exactly how deep it is, or whether this depth is actual or illusory – and this is how we are kept in a vertigo of uncertainty. To put gigantic and capricious reflectors in a celebrated film studio is to stretch to an extreme the traditional link between mirrors and human vanity, which the artist arouses and indulges, only to deform, invert and playfully negate.

This game of reflections and surfaces is regularly punctuated with the terrifying boom of an archaic cannon that is made to go off every few minutes as part of what is perhaps the most estranging, yet riveting, spectacle in the studio, Shooting into the Corner. An attendant in blue overalls comes from time to time and loads a cannon with cylinders of red wax. They come spinning out of the cannon with a great noise and hit the place where two walls meet in front of the cannon. The wax sticks to the wall for a while and then falls to the floor with a soft thud. A dark red pile builds up on the floor, and the walls slowly get covered with what looks like a huge Cy Twombly diptych of blood-red streaks, blobs and splatters.

Left: Installation view of Shooting into the Corner (2008/09) at Mehboob Film Studios, Mumbai, 2010-11. Right: Detail. Both: Photo Mark Prime.

Left: Installation view of Shooting into the Corner (2008/09) at Mehboob Film Studios, Mumbai, 2010-11. Right: Detail. Both: Photo Mark Prime.These patterns and forms made by the wax on the walls and floor are usually read, by a Western gaze preoccupied with terror, as the Gestalt of an ongoing ritual of aggression and violence. But, in India, where bodily effluences are mundane stuff and not always privately encountered, these formations could also be seen – just as powerfully – as magnifications of more everyday theatres of the body: blood-splattered abattoirs and shit-splattered toilets, walls enriched by the long accumulation of spit mixed with the blood-red juice of masticated paan (betel leaves). From the cold emanations of steel that seem to have risen out of the hard, pitted floor of the studio, we are brought back here to the stuff of our private – and not-so-private – knowledge and feelings as we learn to live inside our own bodies and with the bodies of others. But this is not a simple return to the body. It is complicated by the proximity of other materials and forms that play a different set of games and enact a different set of relations with the body. Or, the evocation of the body is effected through rituals and mechanisms that set up an alienating distance from the human and the humane – the shooting of a cannon, or the slowly turning metallic arc endlessly shaping blood-wax into a perfect dome in Past, Present, Future.

In both Delhi and Mumbai, I came out of Anish Kapoor’s shows and went to look at other artists. I stood for a long time in front of Bhupen Khakhar’s Road-building at Kalka in the NGMA collection, and Somenath Hore’s paper-pulp series, “Wounds” brought together and beautifully hung in Mumbai’s Project 88. The unsettling sexuality of Hore’s “Wounds,” bringing to the fleshliness of pulp the fragility and flatness of paper, and the luminous hills and piles of construction material in the background and foreground of Khakhar’s serenely tender painting speak in languages that are very different from those of Kapoor’s works. But these earlier artists had been transformed, to my eye, by my recent encounter with the latter.

I saw Kapoor’s mystical orifices fleshed out with what looked like real hair and blood in Hore’s “Wounds,” and Kapoor’s vividly colored and rigidly upright piles of pigment on the floor seemed to have moved into another, more humbly chaotic story of building, shaping and making in Khakhar’s sublime night-piece. I remembered that Kapoor had called one of his red-wax installations My Red Homeland. But among color, place or matter, who is to say what or where this homeland is in that mysterious work, blood-dark and laid out flat like a ruined, empty theatre? Trying to hold the three artists and their inscrutably shared differences inside my head and in front of my eyes for a while, I wondered whether that homeland is really a no-place, which is restlessly made and unmade only in the most secret places of art.

The Mumbai installation of “Anish Kapoor: Delhi / Mumbai was on view at Mehboob Film Studios from November 30, 2010, to January 16, 2011. In New Delhi, the installation at the National Gallery of Modern Art continues through February 27.

Aveek Sen is senior assistant editor (editorial pages) of The Telegraph, Calcutta. He studied English literature at Jadavpur University, Calcutta, and University College, Oxford, and taught English literature at St Hilda’s College, Oxford. He was awarded the 2009 Infinity Award for writing on photography by the International Center of Photography, New York.