Heat Source and Body Heat: “Art After Human” MOCAF

MOCAF (Museum of Contemporary Art Fukushima), March 11, 2023, Tomioka, Fukushima. All photos (except where otherwise noted): courtesy MOCAF.

MOCAF (Museum of Contemporary Art Fukushima), March 11, 2023, Tomioka, Fukushima. All photos (except where otherwise noted): courtesy MOCAF.

On March 13, the wearing of masks to prevent the spread of COVID-19 infections became a matter of individual choice both indoors and outdoors. No doubt many people are feeling relieved that at long last they are able to put an end to masked life. However, around the time when the WHO declared the COVID-19 outbreak a global pandemic on March 11, 2020, the situation was such that even if one wanted to wear a mask it was difficult to get hold of one in a store. People were touting handmade masks, and the infamous “Abenomasks” (tiny gauze masks named after then prime minister Shinzo Abe, himself no longer around) were distributed to each and every Japanese citizen. Three years later, looking at the crowds of cherry-blossom viewers along the Meguro River today, March 30, 2023, probably just under half are maskless. But in April when schools start up again and new students and new employees begin to fill the streets, the number of people dispensing with masks is likely to increase even further. Undeniably, people’s spirits will also improve. I can also understand people saying they have had enough of their glasses fogging up and having to walk around outside while having difficulty breathing.

Even so, to have reached the stage where we are this obsessed by masks is something that was previously unimaginable. Looking back, after large amounts of radioactive material were scattered mainly across eastern Japan as a result of the serious accident at TEPCO’s Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant triggered by the Tohoku earthquake and tsunami that occurred twelve years ago on March 11, 2011, masks became a necessity of life for people concerned about inhaling this radioactive material. Ten years later, however, masks became an indispensable piece of “equipment” not to protect us from the “external” threat of radioactive material stemming from a nuclear accident, but to contain a virus that might be emanating from “inside” our own bodies (of course, they also function to inhibit the intrusion of pathogens from outside the body). From things to prevent us breathing in radioactive material that might be floating in the air outside, masks became things to prevent us breathing out a feared virus that might emanate from inside of us. One could even say that through masks, a kind of artificial skin, the relationship between outside and inside as they relate to our bodies was “reversed.”

During the COVID-19 pandemic itself, perhaps we were not very clearly conscious of this reversal. On some level we (chronologically) may have sensed it, given that sometime after the fear of being exposed to radiation had passed in psychological terms we began wearing masks again, this time to prevent the spread of infection. Few people, however, were conscious that this was a (non-chronological) reversal of inside and outside as they relate to our bodies, with masks as the “hinge.” But there is one place where the reversal of inside and outside as they relate to masks, a kind of artificial skin, occurred not chronologically, but almost simultaneously. I am referring to the “difficult-to-return zone,” the area that was heavily contaminated as a result of the Fukushima nuclear accident and where entry is severely restricted. Even during the COVID-19 pandemic I entered this zone to carry out maintenance on and document artworks installed inside it, and as well as proving useful in ensuring radioactive material did not get in from the outside, the protective clothing and mask I wore also helped prevent the spread of COVID-19 (or rather, in real terms, they were probably more effective in achieving the latter result). (1) In fact, whether in areas contaminated by radiation or hospitals, in terms of people going about their work wearing protective clothing and masks, when viewed from the outside, the scenes of people after March 2011 and the scenes more than ten years later looked exactly the same (though in reality the relationship between inside and outside had been reversed).

Today, these scenes concerning the human body and this reversal are finally coming to an end – or are they? I cannot help thinking that if anything, these two scenes concerning our bodies foreshadow a different reversal that will continue to occur again and again in different forms, that they are not a thing of the past but will become a model for this future. Because as long as globalism, whose greatest weapon is the immediate, unhindered movement of people and commodities, continues, then the global spread of infectious diseases caused by unknown viruses will continue to occur repeatedly.

And today, we face a new threat of nuclear disaster. In Russia’s military invasion of Ukraine (ie, war), which began during the COVID-19 pandemic, nuclear power plants have often been occupied and have actually been attacked, and there is no telling when this might trigger a nuclear disaster such as a radiation leak. As well, we have learned more than enough to know that even if such a disaster does not occur, nuclear facilities are now targets (subjects of threats) in war. Perhaps even more so we have learned that energy (electricity generation) and food crises stemming from war will inevitably mean not only the restarting and replacement of existing nuclear power plants, but also the building of new ones. The boundary between nuclear wars and nuclear disasters is dissolving. It is now an inescapable fact that viruses and radiation, two invisible entities that exist outside the category of the living, are the greatest incendiary agents in terms of the fate of humankind and will determine the brightness or darkness of our future.

Speaking of war, it appears the world is now being divided in two again like during the Cold War. However, the breeding ground for this new bifurcation is not clear ideologies like those that existed in former times (ideas for supporting systems). The age of ideologies as ideas determining the shape of states is in the past. Instead, the systems that ought to uphold the ideologies people embrace have grown far beyond the scale of human concepts and are running out of control. On one side is the finance capitalism that dominates the “West,” and on the other is the commodity capitalism (for want of a better term) that underpins Russia and the countries that show sympathy for its regime. Put simply, one could say that what is currently dividing the world is the conflict between “finance” (virtual value) and “commodities” (actual value), and the fierce struggle surrounding this. The former is a competition of unsubstantial exchange values and output that continues to expand without limitation in virtual space created by computers (calculators or cyber), while the latter is guaranteed by the earth or by finite matter buried within it (actual energy resources created by commodities). The former can be reduced to the possessions of corporations or individuals, which is to say “people,” but in the case of the latter, even if the earth could be sold by the piece or at the most managed, ultimately it does not belong to anyone and cannot be reduced to people’s possessions. To say nothing of the fact that if commodities are resources that create energy (heat), far from being possessions, they are essential for maintaining human life (heat). Because no matter what, life can never be virtual (death cannot be rendered virtual). And for this reason, neither can it be digitalized. In recent years, entertainment that simulates rejoicing in life using digital characters has appeared, but ultimately this is only possible because the people participating are actually alive (retaining body heat).

Meiro Koizumi – Home Drama (2022). Installation view at “1/12 Don’t Follow the Wind: Meiro Koizumi & Non-Visitor Center,” Futaba, Fukushima, 2022. Photo Kenji Morita, courtesy the artist and Don’t Follow the Wind.

Meiro Koizumi – Home Drama (2022). Installation view at “1/12 Don’t Follow the Wind: Meiro Koizumi & Non-Visitor Center,” Futaba, Fukushima, 2022. Photo Kenji Morita, courtesy the artist and Don’t Follow the Wind.

There is a reason why I have suddenly brought up the subject of the body temperature of actual humans at this point. It is because in the autumn of last year, I had an experience that gave me a renewed sense of its importance. This coincided with the time when one of the venues for “Don’t Follow the Wind” (DFW), an “exhibition that no-one can see” that opened inside the difficult-to-return zone in Fukushima prefecture on March 11, 2015, was opened to the general public for the first time. For those unfamiliar with this exhibition, all of the locations where works are displayed are inside the difficult-to-return zone. The difficult-to-return zone is an area where contamination caused by radioactive material that leaked due to the 2011 Fukushima nuclear accident was particularly bad and where little progress was made with decontamination. As a result, people living inside the zone were forced to evacuate, and for a long time returning there to live (repatriation) was difficult. Of course, members of the general public were prohibited from entering. Most entrances were blocked with barricades and strictly controlled with locks and guards. It was for these reasons that even if artworks were displayed inside this zone, no-one could go and see them. However, around the time when the government came up with the slogan “the recovery Olympics” for the 2020 Tokyo Olympics, parts of the difficult-to-return zone underwent decontamination and at the same time improvements were made to the living environment, and last year the evacuation orders were lifted for these areas, enabling residents to choose to return and pick up where they left off. Some of the locations where the DFW exhibits were installed were inside these areas for which the evacuation orders were lifted.

However, when the evacuation orders were lifted last year, one house inside the difficult-to-return zone that served as a venue for DFW had already been dismantled in accordance with the wishes of the owners, and the work inside the house destroyed. And so even if someone actually went to this place that was now able to be visited, they would not be able to view the work. However, the creator concerned, Meiro Koizumi, made a new choice with respect to his own lost work. While visiting the former location of the house and artwork, he recorded a conversation with the couple who once lived there, which he “re-created” as a new interactive installation. Participants play back using a portable audio player and headsets a work edited together from this recorded material while wandering around the now empty site where the house once stood and the surrounding area. The title of this new work is Home Drama (2022). This also serves as a response by the artist to the lost work, Home (2015). (2)

Meiro Koizumi – Home (2015). Photo Kenji Morita, courtesy the artist and Don’t Follow the Wind.

Meiro Koizumi – Home (2015). Photo Kenji Morita, courtesy the artist and Don’t Follow the Wind.

But what I am about to touch on here is not the actual content of this work or the personal references. These matters have already been covered, so I encourage readers who are interested to refer to the articles concerned. Rather, the important thing about the context up to this point is what it means to open an exhibition in a place where, although the evacuation order had been lifted, it was still impractical for former residents to actually return to live. As well, DFW was poles apart from the “idea (concept)” of an “international contemporary art exhibition that no-one could go and see,” which is to say an exhibition (that had substance but that could not be seen as a reality) that in a sense existed in the imagination and could only be imagined.

More than a concept, the things most essential to an exhibition held in a place where an evacuation order had been issued were heat and light. The main building that stood on the site and that served as the venue no longer existed. The only structure left was a workshop that could be described as semi-outdoors. Water and electricity were supplied so that residents could resume living in the area, but this did not mean that the venue was anything like a gallery equipped with the necessary services. The audio experience begins from the gate near the monitor that shows visitors what the main building looked like. It is now an outdoor space exposed to the elements. Visitors, who had to book in advance and were informed individually of the exact location, arrived within the set times on a Saturday, Sunday or public holiday. Because the work was presented for a month and a half in early autumn, as time passed, darkness fell on the venue earlier in the day and the cold became more bitter. I was reminded of the fact (though if one thinks about it, it is obvious) that in order to open an exhibition a heat source is an absolute necessity. The closing time was set at 5pm, but as the days went by the surrounding area became almost completely dark before this time arrived. Because the work encompassed not only the site where the house once stood but also the surrounding area, there was a danger that visitors would get lost or step into a gutter and get stuck. We could keep track of how many people set off to view the work and how many returned based on the number of headsets, but along the way we also provided flashlights and reflectors for people to use when walking in the dark.

Our concern was not only for the visitors. To keep to a minimum the number of people who know about the site, we avoided taking on collaborators from outside any more than was absolutely necessary. Reception and guiding duties and responding to questions and to problems in the event that they occurred were all handled by executive committee members on a rotation basis. One issue we quickly became aware of was meals. Though visitors made reservations, we did not know when between the opening time of 11am and closing time of 5pm they would actually come. During this time, we could not leave the venue unstaffed. But of course, there was no kitchen where we good prepare simple meals, nor was there a bathroom. For this reason, we worked in groups of at least two, and as for bathroom facilities, luckily we were able to use a portable toilet at a radiation screening station set up nearby. To access it we bought a bicycle. We could also use the bicycle to travel slightly further to the closest railway station, but there was no kiosk. Even if we had money in our wallets, we could not buy anything. Money that cannot be used to buy things is itself a truly meaningless thing. What we really need at such places are heat sources to warm our bodies, water and food to quench our thirst and satisfy our hunger, and light to enable us to cope with the dark. In other words, under such conditions, commodities have more value than money. The value of money is in its ability to be exchanged for other things, so money itself has no use-value. Burning money might produce heat for a brief moment, but one cannot heat one’s body constantly by doing this, and one cannot eat the ashes.

At this time, it was MOCAF (Museum of Contemporary Art Fukushima), which I have written about twice in earlier instalments of this column, that literally came to our rescue. (3) MOCAF opened amid the COVID-19 pandemic at 2:46pm on March 11, 2021, on a vacant lot in Tomioka, Fukushima, where the home of another former resident affected by the Fukushima nuclear accident once stood. The concept was the brainchild of DFW art director and executive committee member Yutaro Midorikawa. On the day of the opening, as the clock ticked down to 2:46pm, there was an announcement concerning the offering of a minute’s silent prayer to the victims of the 2011 Tohoku earthquake and tsunami, followed by a siren sounding. As the siren sounded, each of the people who had gathered for the opening of MOCAF offered prayers in their own way, immediately after which an opening ceremony in the form of a tape cut was performed. And so it was that this unique art museum was opened.

MOCAF (Museum of Contemporary Art Fukushima), March 11, 2021, Tomioka, Fukushima.

MOCAF (Museum of Contemporary Art Fukushima), March 11, 2021, Tomioka, Fukushima.

As described in a previous edition of this column, the only thing installed at the venue was a white-painted revolving door. In other words, MOCAF opened (naturally) with the act of “entering the museum.” However, because which part of this revolving door was the entrance and which part the exit was a relative question, entering could at the same time be exiting. Conversely, it is possible to think of the people who have entered the museum as still being inside. In fact, since it opened on March 11, 2021, MOCAF has in principle remained open all the time. However, with the exception of the one day each year, March 11, when it is open to the public, it is normally impossible to visit the site and “enter” the museum anew. Actual entry by visitors is limited to a set time on March 11. On the day in question, immediately after everyone had completed the entry procedures, the revolving door was dismantled by the visitors and burned as fuel for a “bonfire for the repose of souls,” at which point all traces of it disappeared.

MOCAF (Museum of Contemporary Art Fukushima), March 11, 2022.

MOCAF (Museum of Contemporary Art Fukushima), March 11, 2022.

Last year, after visitors once again gathered for a silent prayer at 2:46pm, the minute’s silence was followed by the opening of a museum shop (or what MOCAF officially refers to as the “Pop-up Museum Store”). During the opening, video and audio was relayed between MOCAF (Fukushima) and the venue of Chim↑Pom’s “Happy Spring” exhibition, then being held at the Mori Art Museum in Roppongi (Tokyo). This, too, has been covered in a previous instalment of this column, (4) but what I want to emphasize here is that MOCAF began with an entrance/exit and a shop, or in other words things that are for most museums introductory or incidental facilities. Normally, when we go to an art museum, we naturally go inside via the entrance. Then, when we have finished looking at the exhibits, there is usually a shop near the exit. And so (if we consider that now, a year after having entered the museum, the first thing we see is a museum shop) it seems that MOCAF may have begun with an “exit” from “here” to somewhere else. This seems all the more likely if the meaning of MOCAF places an emphasis on “leaving (exiting)” traditional “art museums.” And now, the thing that makes me think this even more strongly is that MOCAF, which to coincide with the opening on March 11, 2023, installed its first artwork, has been organized based on the idea that leaving art museums is at once “leaving (exiting)” “humankind.”

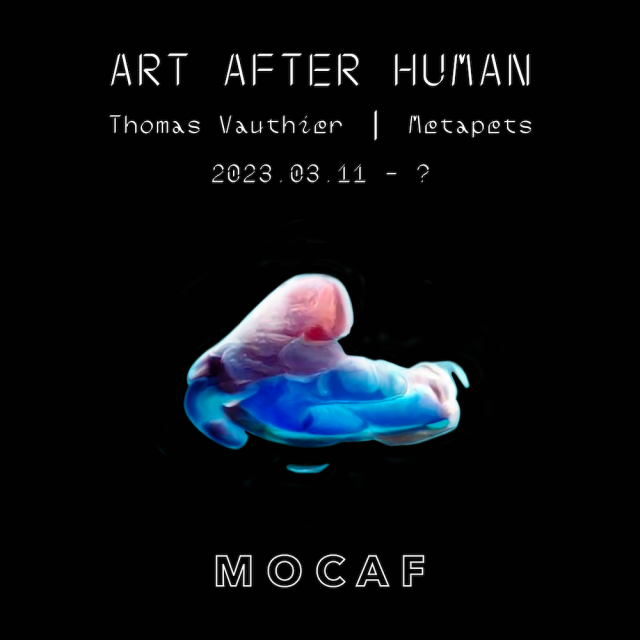

“Art After Human” exhibition announcement, opening March 11, 2023, ending unknown.

“Art After Human” exhibition announcement, opening March 11, 2023, ending unknown.

The title of this exhibition, the first since the museum opened in 2021, is “Art After Human.” In planning it, Yutaro Midorikawa, who is also MOCAF’s director, called in 2022 for artists to submit works for on March 11, 2023, and from among the proposals received from multiple countries selected Metapets by Thomas Vauthier. However, visitors cannot confirm with their own eyes the substance or actual condition of this work. The first year of MOCAF was an introduction in the form of an entrance, and the second an exchange procedure in the form of a shop – both actions as opposed to things that can be viewed – and this same approach has been followed again. Because Vauthier’s work was enclosed in a capsule and buried in advance under the ground at MOCAF. In other words, it is not the visitors of today who are able to engage directly with Metapets, for the aim of this work lies in the far distant future. It will remain buried in the ground until the “non-humans” who appear after humankind has become extinct and disappeared from the face of the earth will in some form or another encounter it and receive it from a different point of view than contemporary “art.”

Given this, what exactly is it that visitors encountered on March 11, 2023? It appeared to me to be none other than heat and light. Because the gatherings at MOCAF serve a function similar to that of ceremonies to console the spirits of the deceased, each year as evening approaches a “bonfire for the repose of souls” is held. Of course, this is partly done with the victims of the 2011 Tohoku earthquake and tsunami in mind, but as touched on above, it has also become an extremely important heat source that provides warmth enabling the visitors who have gathered around the exhibits installed outdoors exposed to the elements to cope with the still cold season and to heat and eat the food they have brought with them. At the DFW venue where the evacuation order was lifted in the autumn of 2022, this “heat source” played an essential role in enabling both visitors and we staff to warm ourselves. Because at the venue for the first public exhibition of DFW, through Midorikawa’s kindness, the MOCAF store was moved from Tomioka and set up near the entrance to the exhibition, and on every day except one Midorikawa ran the store. I cannot stress how much this helped us. It was the MOCAF store so it sold related publications and other items, but it also provided at a moderate price a special blend of coffee made using beans ground by Midorikawa himself and brewed on a small, portable cooking stove. As for the unresolved matter of the staff meals, Midorikawa also prepared these on the same portable stove using fresh ingredients bought each morning at a market. This was truly a heat source of hope (and to put it in extreme terms, one that provided life support).

But this function on the part of MOCAF of providing a heat source to maintain vital activity is not the result of coincidence. At MOCAF itself it has been performed regularly on three occasions in the form of “bonfires for the repose of souls.” However, because they entail the use of flames, bonfires can also be dangerous. Not only lighting the fire, burning the fuel and warming oneself, but the entire process up until the proper extinguishing of the flames is taken seriously. One of the people responsible for these “bonfires for the repose of souls” is Shunyo Art Society painter Mine Oka, who I have introduced in an earlier installment of this column. At MOCAF, Oka has demonstrated some of the skills he uses to take care of the various tasks necessary to lead his own peculiar lifestyle, skills that in the case of bonfires border on wizardry and range from lighting the fire to adjusting and maintaining the strength of the flames, with visitors naturally gathering in circles around the fires he conjures.

MOCAF (Museum of Contemporary Art Fukushima), March 11, 2023. The artist Thomas Vauthier appears in the center photo.

MOCAF (Museum of Contemporary Art Fukushima), March 11, 2023. The artist Thomas Vauthier appears in the center photo.

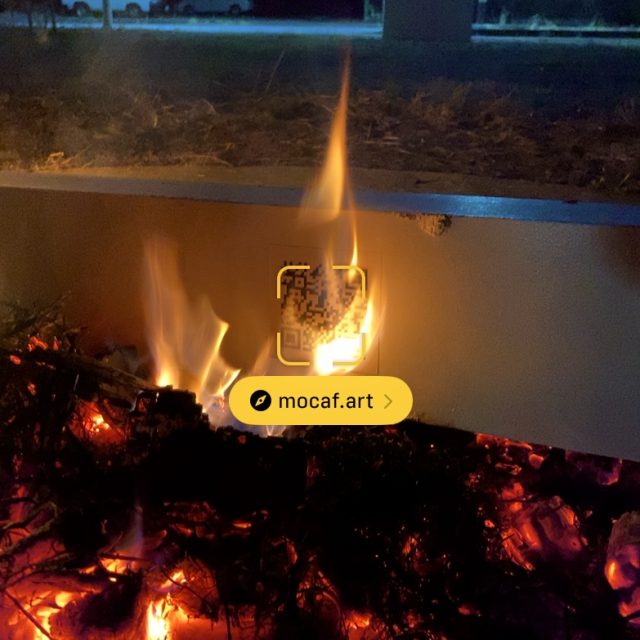

But the encounters with flames at MOCAF are not limited to bonfires. On March 11, 2023, at the place where MOCAF’s revolving door once stood, a white, wooden column was newly installed. On it was pasted a QR code supplied by Vauthier that enabled visitors to access images of Metapets, the work buried underground. Presently, as evening approached, separate from the bonfire, a fire was lit at the base of this column, which gradually went up in flames before ultimately burning to the ground. During this time, the contrast between the virtual information space suggested by the QR code and the real flames that actually rose and gave off heat was striking (the remnants of a white cube as the end point of human civilization which is itself burning down, and the flames able to lead this civilization to both ruin and survival – the strength of nuclear power?).

MOCAF (Museum of Contemporary Art Fukushima), March 11, 2023.

MOCAF (Museum of Contemporary Art Fukushima), March 11, 2023.

All things considered, I am reminded that be it DFW or MOCAF, these art projects inspired by the Fukushima nuclear disaster, an accident concerning a man-made conflagration, both wish for, or rather aspire to return to, something as essential as a heat source that calls to mind primitive flames. Come to think of it, SOMA, the project involving spices pursued by Kiyoshi Izumi that I mentioned in the previous instalment of this column, is also a return to food as a human heat source inspired by the 2011 Tohoku quake and involves cooking, an act for which flames are essential. Even if the act of Izumi providing spice curry to his customers is formally a commercial transaction involving money, it falls far short of anything resembling finance capitalism and is fundamentally also an activity aimed at generating heat inside the body to support life. On that subject, when Naoki Ishikawa, a photographer who travels to the polar regions and high mountains and remote islands around the world, was asked what one should do if they found themselves in a critical situation in extreme cold, he replied that the best thing to do was to eat something. What it boils down to is that eating is a way of maintaining our body temperature. But that is not all. Are not food, clothing and shelter, which are considered the three elements essential to human life, themselves all functions for maintaining a heat source in our bodies? Perhaps this is our “fate” as mammals required to maintain a uniform body temperature. Reptiles and fish appear to have no such need.

However, does this not mean that the most essential things for the life form that is humankind are not wisdom or knowledge, but the maintenance and continuation of body temperature? Certainly, when people die their body temperature suddenly drops and they become cold. To be alive means to have body heat. In this sense, perhaps the “temperature of the time” that independent curator Takashi Azumaya referred to is directly connected to the body temperature of the creators who require literal heat value in the form of their art practices. Surely this is precisely why Azumaya deliberately distinguished these practices from internationalism and globalism, which are premised on remoteness and distance removed from body temperature, referring to them as “ART/DOMESTIC.” Art at a distance where one can sense body heat may be poles apart from the current forms of global art, which is “evolving” through being closely connected to finance capitalism with works such as NFTs becoming increasingly virtual. But for this very reason, in initiatives like MOCAF where both coexist in the same (vacant) space and come into conflict through the medium of fire, I at once sense the “temperature of the time/temperature of the future” and hear echoes of Midorikawa’s own expression, “ART/BEYOND DOMESTIC” (“uncommonly” domestic).

If this is the case, then at the least for humankind today, the crux of the series of initiatives undertaken by MOCAF may well lie in the clear presentation of the flames and the maintenance of body temperature that relies on them as a heat source. The relay of these flames represents the transmission of skills for supporting life carried on between Mine Oka and Midorikawa, who are also father and son, and as long as humankind itself continues as a species, this metaphor can also be interpreted as a metaphor for the body heat (temperature of the time/temperature of the future) transferred from father to son. This is at once a relay of heat (flames) and a relay of life. Furthermore, in the ultimate sense, building a fire on a vacant lot and warming oneself to prevent one’s body from freezing alone can become art. Here, the flames (the heat source) themselves are art.

At this point I am reminded of when Tatsuo Kawaguchi took part in the Independent Art Festival (commonly known as the Nagara River Independent, Gifu) as a member of the group “i.” The group gathered on the riverbed of the Nagara River and over several days dug and then filled in a hole as part of a seemingly meaningless action titled Hole (1965). Unlike later actions such as Nobuo Sekine’s Phase—Mother Earth (1968), which became a “classic” example of the work of Mono-ha, there was no conceptualization carried out prior to this excavation; rather, it even projected a kind of barbarism, on account of which it is still shrouded in a lot of mystery. However, if working up a sweat by moving the body is the surest way by which humans can be certain they are living, then there is probably no purer way of getting to the heart of this than descending on a riverbed in the middle of summer and digging a hole together. In this sense, “holes” (digging holes) are probably not that far removed from MOCAF’s “fires” (building fires). Perhaps this is why I have been deeply interested for some time in “digging holes,” and why, curious to know exactly where along the Nagara River as it flows through the city of Gifu Kawaguchi’s hole was dug and filled in, I showed an acquaintance who lives in the area several photos that have survived and asked him to identify the location. Based on a building from the time that still stands on the riverbank, the spot was quickly confirmed, and so it was that in order to see the place with my own eyes I headed there in the drizzle.

The Nagara riverbed, Gifu, August 12, 2022. Photos Noi Sawaragi.

The Nagara riverbed, Gifu, August 12, 2022. Photos Noi Sawaragi.

Today, the piece of vacant land in question is prone to flooding when the river rises owing to heavy rainfall and entry to it is normally restricted, but when I looked down on it from a bridge, (as one would expect) I saw no signs whatsoever of there ever having been a hole there. To say nothing of the fact that because it is a river, the course and size of the sandbanks are likely different from what they were at the time. However, while comparing with the naked eye the virtual hole in my memory and the riverbed as it actually exists today, I was able to perceive there “some hole-like thing.” To me, it seemed to be at once an act of affirming that humans are truly lifeforms with body temperature in that they are continually moving while breathing and sweating, and an act of remeasuring through the here and now (the temperature of the time) the temperature of the future that had been soenat the time. Though our times are different, both Kawaguchi and I are members of the human race. Which is why I somehow get the sense that in the case of Vauthier’s Metapets, too, which involved MOCAF digging a hole, lowering it into the ground and replacing the removed earth, while the location itself may have already turned back into a wind-swept grassy area, when the “non-humans” of the future encounter traces of this buried work, they will accept it as something like (something with) a “body temperature” that connects with this at some level. As long as the earth is not virtual capital (even NFTs in fact require massive amounts of electrical power, and viruses are naturally accompanied by fever as a symptom), but a commodity in the form of a heat source, I tend to think there will not be a great difference between the two.

1. See Notes on Art and Current Events 92: The COVID-19 pandemic and “Don’t Follow the Wind” – and then there were only “exhibitions that no-one can see.”

2. In conjunction with Meiro Koizumi’s exhibition “1/12 Don’t Follow the Wind: Meiro Koizumi & Non-Visitor Center” the DFW curatorial collective (Chim↑Pom from Smappa!Group [initiators], Kenji Kubota, Jason Waite, and Eva & Franco Mattes) exhibited a video composed of interviews with former local residents and scientists, and footage of animals living inside the zone.

3. See Notes on Art and Current Events 95: ART/DOMESTIC 2021 and Notes on Art and Current Events 100: Back to ‘The Art of Ground Zero’ – War, Plague, Nuclear Energy

4. See Notes on Art and Current Events 100.