DOUBLE WHISTLER

By Andrew Maerkle

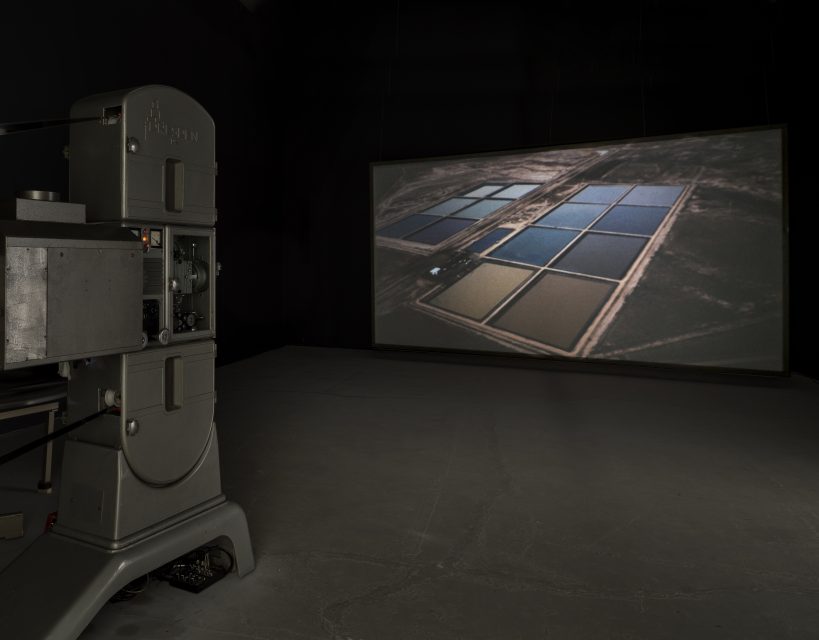

Bending to Earth (2015), 35mm film, color, optical sound, 15 min. Installation view at the 56th Venice Biennale, 2015. Photo Matteo de Fina. All images: Unless otherwise noted, © Rosa Barba.

Bending to Earth (2015), 35mm film, color, optical sound, 15 min. Installation view at the 56th Venice Biennale, 2015. Photo Matteo de Fina. All images: Unless otherwise noted, © Rosa Barba.Rosa Barba makes kinetic sculptures that use film equipment to reveal the cinematic apparatus itself to be an elaborate kinetic sculpture. Incorporating light and sound, film, projectors, and screens, her works feature all the conventional elements of cinema, but deconstruct and reassemble them in ways that allow other bodies to intervene in their mechanics. In Boundaries of Consumption (2012), for example, a filmstrip is looped from a 16mm film projector through a stack of canisters with a pair of ball bearings on top of it to a spool attached to the wall opposite; the spooling of the film destablizes the canisters, setting the ball bearings into motion, while the light of the projector both spotlights the event and converts it into a shadow play thrown upon the wall. In other cases, Barba achieves a similar effect through a more conceptual approach. Accompanied by a percussive soundtrack, the graffiti-like juxtaposition of jagged lines of text onto aerial views of trailer cities and streets in the double-sided projection A Home for a Unique Individual (2013) interrupts the unity of surface and depth in the imagery, reminding viewers of the gaps between illusion and support.

For Double Whistler (2011), in which a single filmstrip with text written on it is looped through two projectors facing in opposite directions, Barba adapts a line from Italo Calvino’s Cosmicomics short story “A Sign in Space” to draw a parallel between cinema and the operation of thought itself:

To think something—had never been possible/

first because—there were no things/

to think about—and second/

because—signs to think/

about were lacking—but/

from the moment—there was that sign/

it was possible—for the two people/

to think of a sign—and therefore that one/

in the sense—that the sign/

was the thing—you could think about/

and also the sign—of the thing thought

At the start of the loop the two projectors are synced so that the fragments of text projected from them make sense when read together, but gradually their synchonicity breaks down, and the text is freed from any obligation to coherence. As with Barba’s other works, this in turn suggests the potential for using aesthetic experience in general, and cinema in particular, to prise open the conventional integrity of mind and body to achieve new modes of perception and being.

Barba is currently participating in the Yokohama Triennale 2020, “Afterglow,” where her 35mm film work Bending to Earth (2015), which identifies radioactive waste sites as documentary inscriptions of human activity in the landscape, is on view at the Yokohama Museum of Art. This follows a solo show at CCA Kitakyushu and participation in the Setouchi Triennale in 2019. ART iT met with Barba in Tokyo in mid-2019 to talk about her work. Inspired by Double Whistler, the below interview revisits the material from that initial conversation while interpolating it with new commentary by Barba herself.

The Yokohama Triennale 2020 is on view at multiple venues in Yokohama through October 11 of this year.

I.

Double Whistler (2011), pair of 16mm film projectors, projected text, 1:33 min. Installation view

at Kunsthaus Zürich, 2012.

ART iT: As I researched your practice in preparation for this interview, I was struck by the way it follows a clear chronological development while also looping back to recurring themes. In response, I’m somewhat disappointed that our interview has to follow a linear format—or, rather, I’m wondering if there’s a way to do parallel interviews at the same time. That’s why I’d like to start by talking about Double Whistler (2011). This work comprises two 16mm projectors placed side by side facing in opposite directions, with both projecting the same strip of film as it loops between them. Although it seems like one of the smaller works in your oeuvre, I find it to be an arresting visualization of two people trying to think something together in tandem—as in an interview or translation. What is your take on this work?

Rosa Barba: I make sculptural studies by modifying analogue machines to operate in ways other than originally intended. The interesting thing about machines—and algorithms too—is that you can never exactly tame them. For Double Whistler, I wrote out a thought on a strip of 16mm film that loops between the bodies of the two projectors. Although the projectors are synced, there’s always a moment where the machines take over and the synchronicity gets disrupted. So the thought will be whole at one moment and then get broken up into two separate entities the next. This describes my filmmaking process as well. I always try to create breaks or gaps for transporting meaning from one layer to another layer, which opens up a different perspective for looking at and thinking about things. The gaps are in a sense intentional, but somehow the machine takes over and decides when they happen. In the case of Double Whistler, the text itself suddenly changes gear along with the machinery. It becomes a nonhierarchical form in which meaning keeps changing all the time.

ART iT: Where did you get the idea for this nonhierarchical form?

RB: I was always interested in it. From the start, I wanted to make films but not linear narratives. I thought film could be a hybrid form that works spatially. I have spent many years looking for a way to access a space beyond what we consider to be conventional cinema. It happens in different ways depending on the work. Sometimes I zoom into something that I want to experiment with. With the smaller works, for example, it may be a balancing act or an experiment with language, while with the longer films it evolves in a different way. (1)

Stating the Real Sublime (2009), 16mm film, modified projector, 2:30 min loop. Installation view at Tate London, 2010.

ART iT: Another technique you use is to turn the apparatus of the work into the content, and the content into a part of the apparatus, as in Stating the Real Sublime (2009).

RB: Yes, you’re not really sure which is which, as they both have the same value. In Stating the Real Sublime, the projector is suspended from the ceiling by the very strip of 16mm film that it projects. For the machine to be hanging there is a very delicate act, but since it’s always off balance, the frame is also constantly shifting around. So the projector is always trying to find its frame, which also then prompts us to think about what we see, or what is in the frame. (2)

ART iT: Your White Museum (2010-19) series resembles an expanded take on Real Sublime, only you’re projecting from inside the museum onto a scene outside.

RB: The work is about using the museum as a container for a projector that then becomes an engine for breaking out to the outside. Usually there is a story in the landscape that I want to capture but which is not really visible. Projecting white film from the museum onto the outside allows a new three-dimensional space to appear. Or rather, connecting the inside and outside with light produces a new psychological or mental space. The first time I did the work was at Centre international d’art et du paysage de Vassivière. I was impressed by how the cinematic white light completely opened up the space outside. It would not have been the same if I had used a spotlight. It was really important to project filmed white light. It did something with perception to transport viewers into the space outside.

White Museum (Vassivière) (2010), 70mm white film, projector. Installation view at Centre international d’art et du paysage de l’île de Vassivière, 2010. Photo François Doury.

ART iT: The idea behind White Museum recalls the concept of “borrowed scenery” in classical Chinese and Japanese gardens.

RB: The Vassivière building was designed by Aldo Rossi. He had conceived of the window I used for the projection as the perfect framing for a landscape painting, and then I used it as an exit. So in a sense the light from my projection produced a three-dimensional landscape painting as well. (3)

ART iT: This also speaks to the feedback loop between representation and the real, whereby our attempts to document reality become representations of reality, and therefore every attempt at documentation only adds more layers of representation between ourselves and the real.

RB: For me the idea of looping back is also about reinscribing a new experience into the existing one in a layering effect. Every time I make a new White Museum piece, it adds a new experience to the series. Each new experience adds a new possibility for approaching the space beyond cinema that is created by projecting onto the outside from within these edifices.

For the first version at Vassivière, I initially thought the piece would only be seen by a single person, because the artificial island where the center is located was created in the 1950s when they made a dam there. It was the largest dam in France at the time. A whole village was flooded. People were forced to move, and their homes disappeared. There was only one man who refused to leave. His house is the last that remains, and he was still living there when I was preparing my exhibition. His presence was important for the conception of the work. Everybody else has to leave the island once it gets dark, so I thought the work would be for him only, although in the end the curators arranged extended hours for people to see it at night. (4)

I | II | III

.

(1)

Drawn by the Pulse (2018), 35mm film sculpture, silent, 3:08 min. Exhibition view at Kunsthalle Bremen, Bremen, Germany, 2018. Photo Marcus Meyer.

Over the course of my critical engagement with moving-image ecologies, I have been on a journey to reveal an imaginary–astronomical–political trope—as in my piece Drawn by the Pulse (2018)—through what can be called the cinema of the present. Through my work, I like to discuss cinema as a sovereign and speculative instrument that interrogates singular qualities of space against the overshadowing regime of film and media archaeologies.

In recent years I’ve been struck by the affinities between astronomy and cinema. On one level, both engage with concepts of light, time, and distance. Indeed, it could be argued that both astronomy and cinema are essentially composed of only these elements. On yet another level, both can be understood as sharing, in different ways, fundamental aspects of uncertainty and speculation. Only a very small part of an astronomer’s education is based on factual knowledge. That is to say, an astronomy student can acquire all their factual knowledge in a very short time, as it forms only 4 percent of their studies. Everything that follows moves beyond fact into a space of research and speculation.

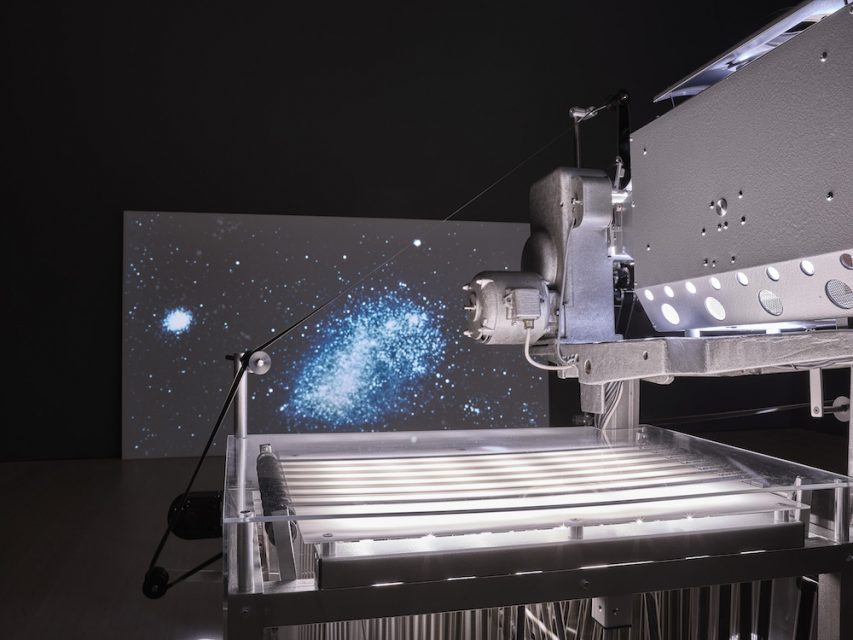

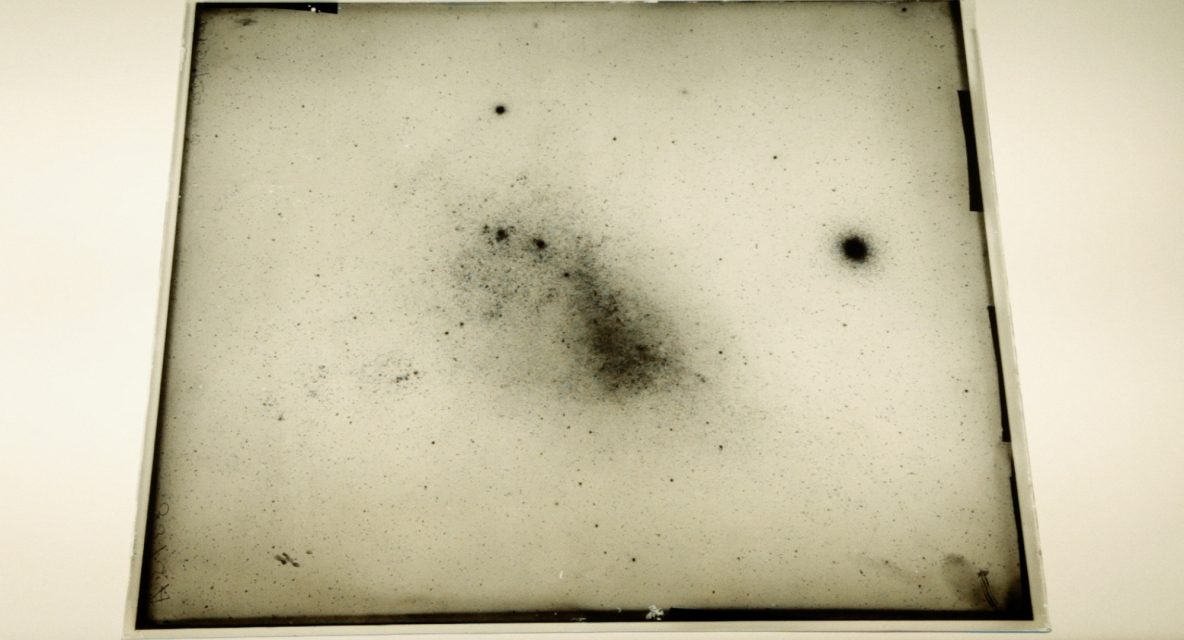

Drawn by the Pulse was filmed at the Harvard Astronomical Observatory. The work draws on research by the American astronomer Henrietta S. Leavitt—namely, her discovery that distances in the universe can be measured based on the relationship between the luminosity of variable stars and how fast the stars appear to flicker or blink. Arid, expansive landscapes—mainly deserts—and the relationship between film and astronomy are the starting points for many of my pieces. Both spaces—desert and cosmos—are capable of preserving documents of the relations between human beings and nature, and the reciprocal influences the two exert on each other. Deserts and astronomy also share something else: the encounter between old and new technologies—a coming together prompted by how they are used, as happens with deserts, or by the need to see what is out of sight, as is the case with astronomy. Based on the relationship between the environment-as-document and the machine—the machine of vision—as well as a complex conception of time generated by the timelessness of vast spaces without geographical limits, I propose works of an enigmatic nature, works of a certain opacity, that address the transformations of society and the changing ways in which we relate to society. Through Leavitt’s “flicker,” we come to understand that the universe is much larger than we believe.

.

(2) For me, a machine performs activity: you can see how one thing leads to another, and everything can be examined. When I invent a new machine, it involves playing with these elements. I discover another aspect of cinematic expression by separating an element by itself, or inventing an element that hadn’t been there before. It is this positive act of introducing the element of play that goes against conventional notions of cinematic production. I question the regularity and closure of the world of production by introducing play: anything can happen. Play here does not indicate a game with rules, but instead functions in a more philosophical sense, suggesting a ludic mentality and quality.

Machines can be made to do other things. They can be used as one component of many to orchestrate a body of experience through working with the “autonomy of the material” and with space in a very physical and almost tangible way. The significance of these interventions in the operation of the machines is that they can break the grip of utilitarian and functional definitions of the world and introduce new possibilities and shades of meaning and experience. Fragmenting and translating the meaning constantly from one thing to another, or keeping it in motion or unstable opens up these possibilities. It allows for a “second becoming.”

.

(3)

White Museum (South Saskatchewan River) (2010/18), 70mm white film, projector. Installation view at Remai Modern, Saskatoon, 2018. Photo Blaine Campbell.

More recently, in White Museum (South Sasketchewan River) (2018), the 70mm projector projected white film onto the Saskatchewan River from the Remai Modern Art Museum in Saskatoon. In carving a white rectangular frame onto and out of the dark river at night, the history of the river was highlighted or further inscribed through the light: Indigenous peoples have inhabited the South Saskatchewan River Basin for over 10,000 years, fishing from the river and hunting bison, woodland caribou, moose and small mammals. While cinematic light here bridged the new architecture of the museum with the landscape, directing the light beam onto the river also articulated another kind of viewing area.

.

(4)

Send Me Sky, Henrietta (2018), 35mm film sculpture, silent, 6.20 min. Film still.

Through researching astronomical questions related to the exploration of space as concept, a reconfiguration of cinema’s conceptual space can be reached by proposing ways of making cinema that embody and exploit the expanded dimensions of that reconfigured conceptual space. Here, the discovery of flickering stars by Henrietta Leavitt and my research on her work—which resulted in the film sculptures Drawn by the Pulse and Send Me Sky, Henrietta (2018), and resituated earlier pieces on astronomical investigations like The Color Out of Space (2015), as well as the White Museum series (2010–)—have conflated and expanded conceptual ideas of cinematic spaces.

Rosa Barba: Double Whistler