II.

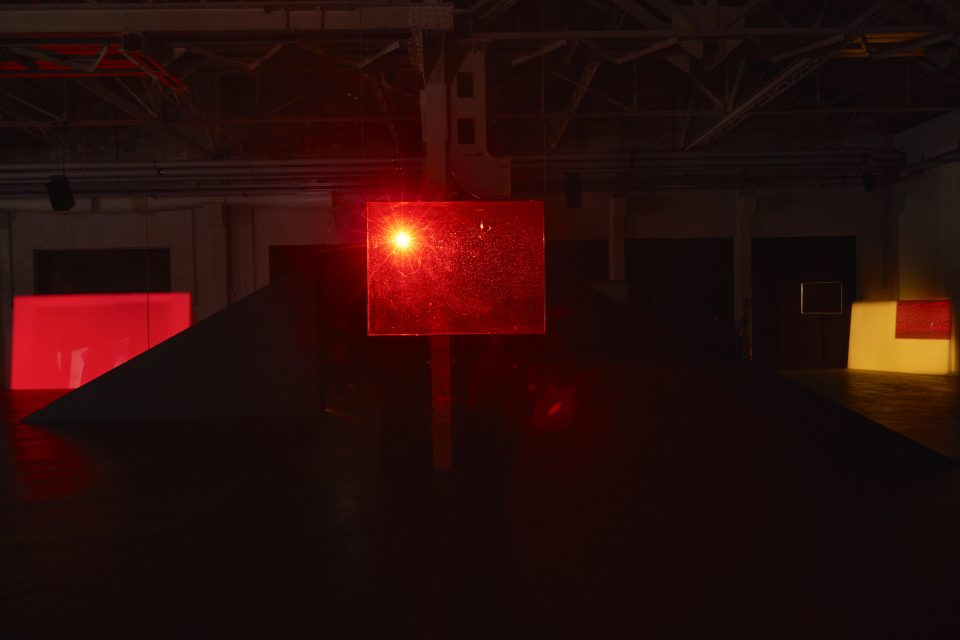

“Rosa Barba: From Source to Poem to Rhythm to Reader,” exhibition view at Pirelli HangarBicocca, Milan, 2017. Photo Agostino Osio. All images: Unless otherwise noted, © Rosa Barba.

ART iT: I remember seeing your show at HangarBicocca in Milan in 2017. The space had so many works in conversation with each other that it was both exciting and disorienting. I felt like I had been dropped into the middle of an orchestra pit. It gave me the sense that each work you make is a form that you can then combine with other forms to create bigger forms that can then become immersive forms. What’s your approach to the relations between your works and the spaces where they are displayed?

RB: I’m always interested in working with the architecture of the space itself. HangarBicocca has a very strong ceiling, and I started imagining what would happen if the ceiling collapsed. What components would you see? I used these imaginary components to create small “auditoriums” for giving viewers a more intimate view of each work. You could sit down, put the headphones on, and just be with that work. But there was another work, Hear, There, Where the Echoes Are (2016/17), which spread across the whole space and interacted with the architecture as well as the other works. It had a sound element that initially might have been noisy or disturbing for some viewers, and required some getting used to. But it also moved people along from one work to another and helped them to understand that there was a conversation going on between the works.

I also look for ways to dialogue with the outside, as in White Museum. At HangarBicocca I did this by presenting a work I developed in 2013 during my residency at the Chinati Foundation in Marfa, Texas, Perpetual Response to Sound and Light (at the Locker Plant). The residency studio is housed in an old locker plant with a big window facing some train tracks. I could see huge trains passing by. Of course, the trains were always announced by the sounds they made before they actually came into view—the sound can travel quite a distance in the desert. For the work, I placed sound detectors under the railway tracks and pointed a massive surge lamp at my studio. The lamp was activated by the sound of the trains. When a train approached, the ground would start to vibrate as much as 10 minutes before its arrival, and then the sound would gradually get more intense. Once the train was close, the lamp would pump light into the building, and for a few seconds the building would become a light sculpture. I invited the people of Marfa to come see this performance for a few evenings. But since the trains transport sensitive materials, they follow a secret schedule, and that raised the question of how I could plan the performance. In the end I decided to make the uncertainty part of the concept. The event would last three or four hours, and during that time only one train might pass, or three or five trains might pass.

It turns out that HangarBicocca is also next to a train station, so I was interested in repeating this work in a new context. We replaced one of the doors of the space with a window and set up a lamp outside. But this time I knew the train schedule, so I programmed the work to respond to specific trains.

ART iT: In the HangarBicocca installation it was as though the exhibition unfolded across multiple parallel time tracks. The idea of deploying multiple screens or works to create a “choreographed space” initially implies that the display choreographs the movements of the viewer, but conversely the viewer also gets to be the editor of the space as they turn their attention from one work to another and then back again.

RB: Since we are increasingly forced to watch films in a certain way, and look at visual information in the city in a certain way, our consumption of images is increasingly dictated to us by our environment. In response, I try to create an “anarchic organization of cinematic space” in my films and larger exhibitions. Anarchic organization attempts to build a foundation for thinking and acting by destabilizing the old hierarchies of film’s components. It gives viewers more freedom about where to look, what to read first, how to bring all of these narratives together, and, indeed, how to edit the space. Everybody carries different experiences and histories, so they each have their own way of looking at film or reading text. Of course the work is there and I choreographed, shot, and edited it, but I think there is still a possibility for viewers to move around inside it freely.

Above: Hear, There, Where the Echoes Are (2016), 4 x 16mm projector, 4 glass filters, 35mm projector, screens, sound. Installation view at Pirelli HangarBicocca, Milan, 2017. Photo

Agostino Osio. Below: Perpetual Response to Sound and Light (at the Locker Plant) (2013), spotlight, sound, specially programmed Max/MSP patch. Installation view at Locker Plant, Chinati Foundation, Marfa, Texas.

ART iT: So in a way you are taking apart your own films, or opening the doors for someone to de-edit the work, so to speak?

RB: Other dimensions of sonic experience also come into play that are distinct from the norms of cinema, where one is immersed in a sonic bath or the speech is hypnotic and the conversations between characters follow a script that creates a certain atmosphere that lulls you into the appropriate behavior of the right consumer.

Another aspect of the reconfiguration into anarchic cinematic spaces is the opening up of new unexpected and self-organizing spaces for viewing and hearing. Here, the idea of autonomy is also the freedom to play around, where I, as artist, make the decisions. There is an author at work, and not merely a runaway effect of the structure itself. This freely made decision of working with the material and the machine can give access to new sculptural spaces that are carved out of the apparatus.

ART iT: Although I was aware of the sound of the projectors and other equipment when I saw the exhibition, for some reason I don’t recall hearing the drums in the soundtrack.

RB: Well, it was quite an intense exhibition setup. It was my first time presenting Hear, There, Where the Echoes Are in a broader exhibition context. The work started out as a collaborative performance with the jazz drummer Chad Taylor. We developed it for PS1 in New York in 2016. In the performance, all the different frequencies of the drum kit are connected to corresponding 16mm films and projectors, and the frequencies trigger shutters that I place in front of the projectors. Chad basically edits the films as he plays.

I asked Chad to come to HangarBicocca to make a new version for the space with me. The recording played every 10 or 15 minutes in the exhibition—you may remember seeing the colored projections on the leaning Plexiglas sheets, for example. While this was happening some of the other works would pause for a bit, so it was like an intermezzo for the whole exhibition, a kind of reorganization of the space.

Above: The Long Road (2010), 35mm film, color, optical sound, 6:14 min. Film stil. Below: Time as Perspective (2012), 35mm film, color, optical sound, 12 min. Installation view at

MIT List Visual Arts Center, Cambridge, MA, 2015.

ART iT: The idea of de-edited exhibition space also parallels the way that we relate to archives, in the sense that an archive is a body of knowledge or information that we can never experience as a totality, only piece by piece. You can take things in and out of the archive, you can reorganize them according to different search terms or indexes, but there is no way that you could actually work with the archive as a whole.

RB: Right. And the idea of the archive always comes back in my work because I also understand many things as archives—for example, the landscape. I have done many works in the desert where I look at how human inscriptions in the landscape become an archive of sorts that will allow people in the future to understand our society. One of the first films I made in this direction was The Long Road (2010), for which I filmed an abandoned racetrack from a plane using a handheld camera. In this case, I saw the camera as a drawing instrument. My whole body was involved in carrying this heavy camera and then drawing with it in the air, as though I were making a drawing of the circle I saw below me. Similarly, Time as Perspective (2012) features oil pumpjacks in Texas that are constantly inscribing the landscape like sewing machines or clocks.

Another work in this vein is Bending to Earth (2015). The radioactive fields in the film also relate to the concept of time, because they will last longer than the earth has existed till now. That is such a huge concept that we lose our comprehension of time when we work with these kinds of materials.

I’ve also done several works where the archive is more like a museum archive. Here, I’m interested in the hidden conversations that go on between things in a storage facility. For example, I shot From Source to Poem (2016) at the US Library of Congress’s National Audio-Visual Conservation Center. (1)

I | II | III

.

(1)

From Source to Poem (2016), 35mm film, color, optical sound, 12 min. Film still.

My 35mm film From Source to Poem (2016) is an invitation to think about the spaces where history and cultural production are preserved for passing on to future generations.

On the one hand, this work continues the research I initiated with The Hidden Conference (2010–15), a three-part film work exploring museum storage systems. The title refers to imaginary conversations taking place between the artworks inside these invisible spaces and between their creators, who often were not actually contemporaries—and yet their artworks continue to speak across different generations.

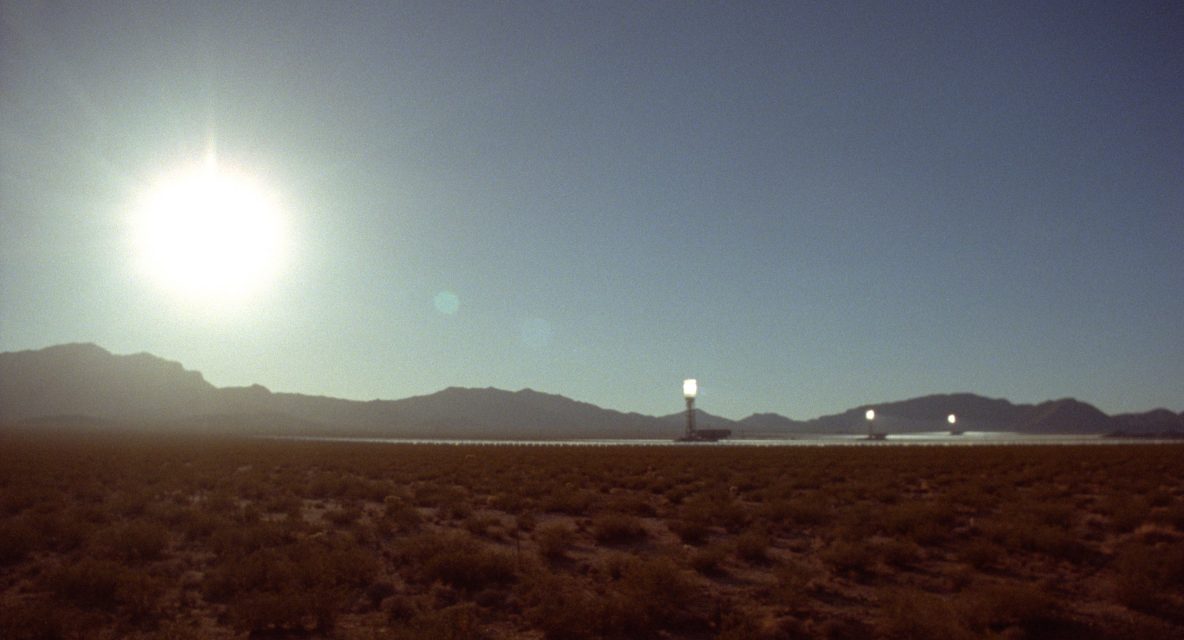

On the other hand, as a reflection on Western culture’s obsession with preserving all of its output in all possible mediums, From Source to Poem shifts the focus from artworks to archival storage itself. Shot at the National Audio-Visual Conservation Center (NAVCC) at the Library of Congress in Culpeper, Virginia, and at an enormous solar power plant in California, it juxtaposes images from the largest media archive in the world with a study of rhythm, and images of cultural production with those of industrial production. Like the temporal property of two things happening at the same time, the interval determining the coincidence gate is adjustable.

The film responds to the question: How has digitization collapsed the modernist categories of time, space, and materiality, and created instead an abstraction? In doing so, it attempts a continuation of the thought possibilities of archives, bringing together the sources in the NAVCC with their connections. These can be different kinds of inscriptions in the landscape that we leave behind yet whose meaning can’t really be translated or projected into the future. They can also be documents, and even rumors—narratives that people haven’t written down but which just exist somehow as source material in oral form. I began to conceive of the Library of Congress and the NAVCC media archive as being some sort of white noise, as all the information and all the sources they contain become so compressed that the archive can be compared with light. That is what led me to filming solar power plants in the desert where actual light energy is collected and turned into electricity, and then setting these images against each other alongside texts about the history of the NAVCC and of the building itself, which was actually built as a nuclear bunker during the Cold War—a simultaneous existence and composition of simultaneous order.

The film starts with all these facts and then navigates toward thinking about what this archive could mean. So in a way it turns into a sort of poetry. But primarily the poetry is in fact found in the soundtrack, because it consists of a lot of free source material from the Library of Congress—including interviews with field workers, formerly enslaved people, Native American poets, and more. It became a very dense composition of all the voices that constitute the United States.

Rosa Barba: Double Whistler