THE ANTI-SOCIALLY ENGAGED ARTIST

By Andrew Maerkle

Artistic Dandy (2018). All images: Unless otherwise noted, installation view, “Ground No Plan,” Aoyama Crystal Building, Tokyo, 2018. Photo Kei Miyajima, © Makoto Aida, courtesy Mizuma Art Gallery, Tokyo.

Artistic Dandy (2018). All images: Unless otherwise noted, installation view, “Ground No Plan,” Aoyama Crystal Building, Tokyo, 2018. Photo Kei Miyajima, © Makoto Aida, courtesy Mizuma Art Gallery, Tokyo.

One of the most polarizing figures in Japanese art over the past three decades, Makoto Aida treads a fine line between provocativeness and boorishness. Born in 1965 in Niigata Prefecture, but long based in the Tokyo area, he has made a career out of taking the piss out of international contemporary art and its attendant pretensions, while simultaneously skewering the chauvinisms and insecurities of Japanese society. His works range from paintings of naked, mutilated young women, depicted in chains and posed on all fours, to videos in which he impersonates political figures like Osama bin Laden and the current Japanese prime minister Shinzo Abe, and a banner-sized manifesto, composed with his wife and son, complaining about the faults of the Japanese education system. He is admired by many for his acerbic, protean wit, willful inconsistency and embrace of failure. On the other hand, in a post-3/11, post-Trump context, he is also open to critique for his perverse nihilism and tacit reinforcement of the power structures he outwardly seems to defy – not least of which is the institution of art itself. At a time when younger artists and art practitioners are looking for ways to bridge art, politics and community, Aida steadfastly refuses to justify his work – whether as genuine sociopolitical commentary or as the acting out of a constructed persona.

Aida’s latest project, the exhibition “Ground No Plan,” was produced as the inaugural event of the newly launched grant program “Visions of the City – Obayashi Foundation Research Program.” Sponsored by the Obayashi Foundation, which is backed by one of Japan’s biggest construction conglomerates, the biennial program invites artists to investigate issues related to urban space and make proposals for alternate approaches to urban planning. Chosen as the first recipient of the grant, Aida responded with characteristic irreverence, displaying a series of drawings, paintings, maquettes and installations about the built environment that exaggerated the futility of utopian thinking.

ART iT met with Aida after the exhibition opened to discuss the ideas informing the project, and reflect on his career to date.

“Ground no Plan” was on view as a site-specific installation at the Aoyama Crystal Building, Tokyo, from February 10 to 24 of this year.

I.

ART iT: This is my third time interviewing you. The first time, in 2008, I visited your home in Chiba and we spoke for several hours. The second time was five years later on the occasion of your solo show at the Mori Art Museum in 2013. Now here we are again in 2018 after another five years have passed. I think it’s a good moment to discuss this exhibition in relation to your overall practice.

First, since I tend to take things seriously, I always ask you about the political content and critical stance toward society expressed in your works. So far, you’ve tried to skirt the issue by replying that you are a “Pierrot” or by downplaying the social implications of your works. But in the exhibition here you touch upon some of the most urgent issues affecting Japanese society today. Has anything changed in your thinking over the past years?

MA: Well, I’ve certainly gotten older. I’m approaching the transition from middle age to seniority, so maybe I’m starting to act more like an elder instead of a youth who runs around recklessly – although I don’t think that’s necessarily a change for the better. Or maybe as my son has grown I’ve also become more fatherly, and that kind of unconscious life change is reflected in the work.

ART iT: Even if you don’t deal with it directly, would you say you are addressing issues here such as the dominant role of real estate development conglomerates and the Liberal Democratic Party in shaping Japanese society?

MA: Man, you’re getting straight to the tough questions! My basic thinking has not changed from five years ago or ten years ago. I have my opinions about politics as a voter, but I don’t think art exhibitions are the place for promoting those ideas. But it’s fine if my individual political inclinations leak out or leak into the work. And, sure, there have been a lot of leaks this time.

Above: “Grand Plan to Alter Shinjuku-Gyoen National Garden” Diorama (2018) in foreground with Grand Plan to Alter Shinjuku-Gyoen National Garden (2001) in background. Below: “NEO Dejima” Diorama (2018).

Above: “Grand Plan to Alter Shinjuku-Gyoen National Garden” Diorama (2018) in foreground with Grand Plan to Alter Shinjuku-Gyoen National Garden (2001) in background. Below: “NEO Dejima” Diorama (2018).

ART iT: So when you make works using the figure of the salaryman, for example, are you using it more as a trope than as a comment on the state of Japanese society as a whole?

MA: First, the reason this exhibition ended up the way it did is because of the framework of the project, with me being selected as the first participant in “Visions of the City – Obayashi Foundation Research Program.” For a normal exhibition I would think up my own framework, whereas this time the framework was decided for me. I’ve made works about public space now and then, starting with Grand Plan to Alter Shinjuku-Gyoen National Garden (2001), but never had so much confidence in the genre as to want to do an entire exhibition on it. Since I was chosen for the research program, I thought I should try putting my weight into it this time. You could say I pushed myself beyond my limits.

But now I’m thinking that, in response, my next exhibition will have to be nothing but paintings. My previous exhibition of bento box works at Mizuma Art Gallery in 2016, “Let us dream of evanescence, and linger in the beautiful foolishness of things,” was all about painting, color and form. So if my response to that exhibition was to make this exhibition of works with a strong social context, then next time I’ll go back to doing the opposite. It’s not like I’m planning on becoming more of a social artist just because of this exhibition.

ART iT: Yet the picture of you that emerges from what we could call your “self-curation” here, with its mix both new and old works, is of an artist who has consistently displayed a concern for social issues.

MA: I suppose so. But although the theme of the project is “Visions of the City,” there’re also some works here that are clearly off topic. For example, the work in the back of the basement about trying to come up with new types of fermented foods, Discover the Element of New Taste! (2006), seemingly has nothing to do with “Visions of the City.” But when I started putting the exhibition together in my head, I realized that maybe it’s not entirely unrelated, and decided to include it. Or there was the time I tweeted about having refugees work the rice paddies, which got everyone upset. I wasn’t commenting on Twitter as part of my practice. I just made a casual comment and then it turned into something else. Then I had the idea of presenting it here as (Twitter) Storm in Terraced Rice Fields (2018).

So, as always, it’s not like I say, OK, now I’m going to decide to make a socially critical or political work. There are probably artists who directly challenge the government through their works, but I’m just not suited for that, which is why I have a lot of works that relate to those issues in what you could call a roundabout way. That’s just my quirk or characteristic.

ART iT: But this exhibition is highly critical of society. For example, your “NEO Dejima” Diorama (2018) depicting an international enclave that has been built on top of Tokyo’s existing government district mocks historical tensions in Japan between isolationism and openness while also presenting a vision of a global class structure in which international elites live on the backs of exploited locals.

MA: You know, what led me to make that work was that I had been to Singapore and Hong Kong for projects and started thinking about how they differ from Tokyo. English is the official language in both cities – which of course has to do with their being former British colonies – and they are in fact more international than Tokyo. Tokyo, or Japan, has fallen behind them, and continues to fall behind. So there was a sense of danger for me, but at the same time a sense that former colonies like Singapore and Hong Kong also have their unfortunate or unnatural sides too. It’s like I was caught between envy on the one hand, and the feeling that life in Tokyo is actually healthier and better on the other. It didn’t immediately occur to me to turn that experience into a work, but once I hit on the idea of coming up with ridiculous proposals for redeveloping Tokyo, I remembered those impressions from my travels and they somehow took shape in “NEO Dejima” Diorama.

Specialists such as urban planners and architects have to investigate the dilemmas in a project and come up with the most appropriate plans for resolving them. But as an artist, I like presenting the dilemmas or contradictions the way they are. I believe that artists are allowed or even expected to do it this way, and that’s how I’ve done it so far. If someone wants to call it social critique or criticism, then that’s fine and I won’t deny it. But as a creator, I guess I have the feeling that the word critique implies a kind of arrogance in telling society and people that they are wrong and that you have the right answer – when the truth is that’s not how it really works. It’s not like I have a solution!

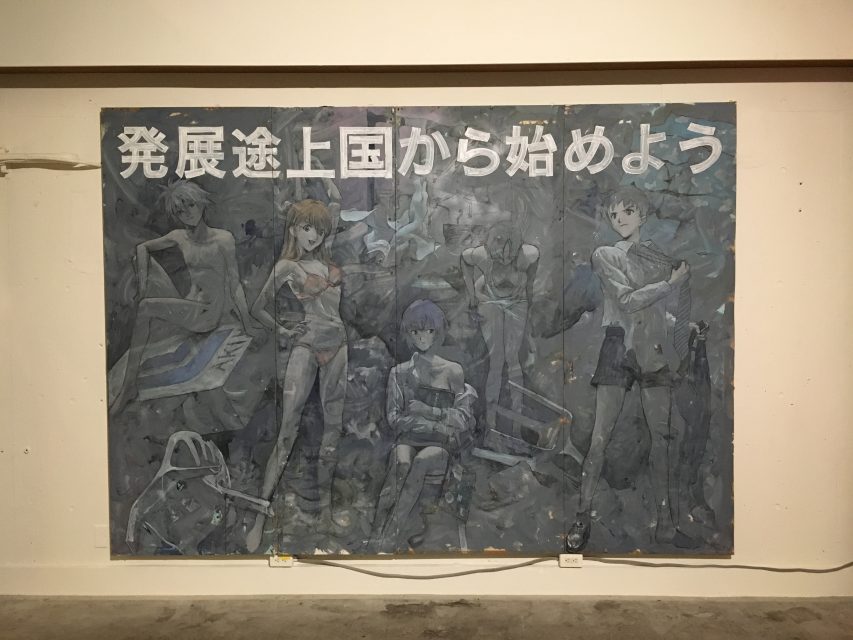

Above: Let’s Start from the Developing Countries (2018). Below: From left to right – Transferring the Capital to Hokkaido, Tokyo 2020 and Plan to Remove Humanity from Peninsula X (all works 2018). Both: Photo ART iT.

Above: Let’s Start from the Developing Countries (2018). Below: From left to right – Transferring the Capital to Hokkaido, Tokyo 2020 and Plan to Remove Humanity from Peninsula X (all works 2018). Both: Photo ART iT.

ART iT: You’ve incorporated symbols of Japanese nationalism such as the national flag and the Meiji Memorial Picture Gallery building in your works here. Does that not come from a desire to assess the current state of Japanese society?

MA: I’m not sure I can give you a good answer. A lot of the works on display downstairs developed out of associations between one image and another. For example, I already had the idea for the painting Let’s Start from the Developing Countries (2018), which depicts the protagonists of the anime series Neon Genesis Evangelion taking off their clothes, before I was invited to do the research program. But initially I was imagining something like the big posters you see at Shinjuku station, and planned to have some kids pose for me to make a photograph. It was only later that I realized Evangelion would work better, and made it into a painting.

Necktie Building ∞ (2018) also started off as a small rectangular picture. Since I was supposed to propose a vision for Tokyo, I wanted to show how drab most of the buildings are and how depressing the urban landscape is here, but as I thought about it, I realized the image could connect to a broader theme, so I enlarged it and turned it into a Möbius-strip-like infinite loop. The image of the tattered Japanese flag came out of that. It’s not meant to stand alone as an independent work. I just thought it would be good to have something like it there as part of the installation – as one of the multiple images that would get mixed together in the minds of the viewers on site.

To put it bluntly, I guess I’m really concerned with the way Japan has been declining since the collapse of the bubble economy. Of course we can question whether Japan really was so good back then or whether the period when Japan had the most money was really such a great time. But now when I go online to see how society is changing, it feels like articles about Japan’s decline and deterioration come flooding in to me almost every day, even when I’m not actively seeking them out. To be honest, they exert a powerful control over the images in my head. So first it’s a reflection of that.

Of course, even though the title is Let’s Start from the Developing Countries, I’m not saying that if we all take off our business suits and go naked then we’ll necessarily find a better way of life. To state a common opinion, I think you have to be desperate to do business. It’s just that I’m betting on the special effect of art, whereby extreme images can prompt changes in thinking.

ART iT: Of course, since the bubble economy was itself a phantasm or mirage, isn’t it misguided to think that we should bring it back?

MA: Yes. That applies to the bubble economy, and also to the current Japanese government’s campaign ahead of the 2020 Olympics to recapture the vitality of the period of high economic growth surrounding the 1964 Games. I understand the desire, but I don’t think it’s very effective.

ART iT: On the other hand, your ridiculous proposals for redeveloping Japan, visualized in works such as Let’s Make Gunma Prefecture into a Huge Lake or Plan to Remove Humanity from Peninsula X (both 2018), seem to be an acute satire of the top-down methods of the Japanese government, and a reflection of the totalitarian or authoritarian tendencies that occasionally appear in Japanese society.

MA: Whoa, hang on a second! I think I need to go for a cigarette to cool my head . . .

OK, so I was thinking about your question as I smoked. Yesterday I happened to watch a screener of Ruben Östlund’s film The Square, since I was asked to write a commentary on it. The protagonist is a curator at a contemporary art museum, and in the film we see a number of artists working with typical “socially engaged art.” This is something that had already occurred to me before, but I think that my style is different compared to that of a certain type of international contemporary artist. I’m not saying I’m better, just that I’m different. Your questions so far expect me to be some big artist who critiques the government and society, as they do in the US and Europe, but that’s just not me.

There’s a secret smoking room where I went just now, hidden behind the video installation of me singing karaoke as Joseph Beuys, Artistic Dandy (2018), so I could hear the song as I smoked. I mean, probably no serious artist anywhere else in the world would make a work like that. But the work is not an arrogant critique of the kinds of socially-engaged artists epitomized by Beuys. It’s more an expression of my doubt that they would ever let me join their club. I guess that’s where my tendencies show through.

Like, I’m on Twitter. There are all kinds of anonymous, ordinary people on Twitter – salarymen or what have you – who discuss politics and society really passionately. My gut feeling is that I do not have any better opinions than those people. I’m just one person commenting on Twitter. I say what I think, but I don’t believe there is any reason that I should have some special right to speak just because I’m an artist.

What I can do is make a more attractive exhibition, which I have a certain know-how for doing because I’ve done it any number of times now and I’m a professional at it. It looks like a lot of people have been coming to see this exhibition, and, if I say so myself, I seem to be pretty loved by them. I think one reason may be that I’m not the kind of artist who is overbearing and looks down on others from on high. I have the sense that they appreciate my sort of humility. I think that’s something I should always appreciate – but maybe that’s not the answer you were expecting.

Weed Cultivation (2018).

Weed Cultivation (2018).

ART iT: Believe me, I know you well enough not to expect anything!

But, for example, last year there was the big Tadao Ando exhibition at the National Art Center, Tokyo, which attracted several hundred thousand visitors. Ando has a charismatic persona or even, say, Beuys-like qualities, and the exhibition suggested that Ando’s architecture is working toward building a better world. In fact, many visitors commented on Twitter about how amazing the exhibition was, with almost everyone voicing positive opinions about it. In contrast, although we can’t say for sure how deep they will read into it, the people who come to this exhibition and see your “NEO Dejima” Diorama will be directly confronted by a vision of an architecturally stratified society, and as they look at the other works, they will encounter other issues that are not usually addressed in the mass media here.

MA: You know, I purposely decided not to go see the Ando exhibition because I didn’t want it to affect my preparations for this exhibition. When you mention Ando, I get the image of some kind of concrete, rectilinear form – kind of like the title of the movie The Square.

To be impressed by squares is of course also part of the minimalist aesthetic, but I think what people originally got out of it was a sense of relief at having been given an answer by someone with a godlike perspective who came and dropped a hard-edged square into what was originally a mess in its natural state, with the premodern, idiotic masses jerking around all over the place. That’s what real architects and certain kinds of contemporary artists do. But the vision that spontaneously came to mind for this exhibition was anti-square, anti-flat, anti-perpendicular.

What most concretely and simply expresses that vision is the work Ape Graduate of the Oil Painting Department (2018), for which I went on Yahoo Auction to buy one of those drafting tables that architects use for rendering horizontal and vertical lines, then painted all over it in salad oil and colored pigment. I’m making fun of myself, of course. Then, in response to that there are the “2nd Floorism” works, which start from my declaration that I like slums and think they are beautiful and good. This is also a statement of my dislike for or even rejection of the world of those top architects and minimal artists. That was one reason why I didn’t go see the Ando exhibition.

But squares also have this ambivalent side to them – like, when you really about it, of course it’s better to have a square house. For the Weed Cultivation (2018) installation, I chose to work with square-shaped plastic packages like those used for natto fermented beans and what have you. Since the packages are all of differing sizes, it’s not possible to line them up neatly like a chessboard, but they still maintain some kind of order when they are packed together. And that’s actually how a lot of shantytowns end up. Then I put the model train track running around the whole thing to suggest just the right amount of order.

Of course, everything I say is totally illogical. It’s contradictory and inconsistent. Even with squares, I’m neither completely negative nor affirmative. It’s more like I just stop where I feel like it.

I | II

Makoto Aida: The Anti-Socially Engaged Artist