II.

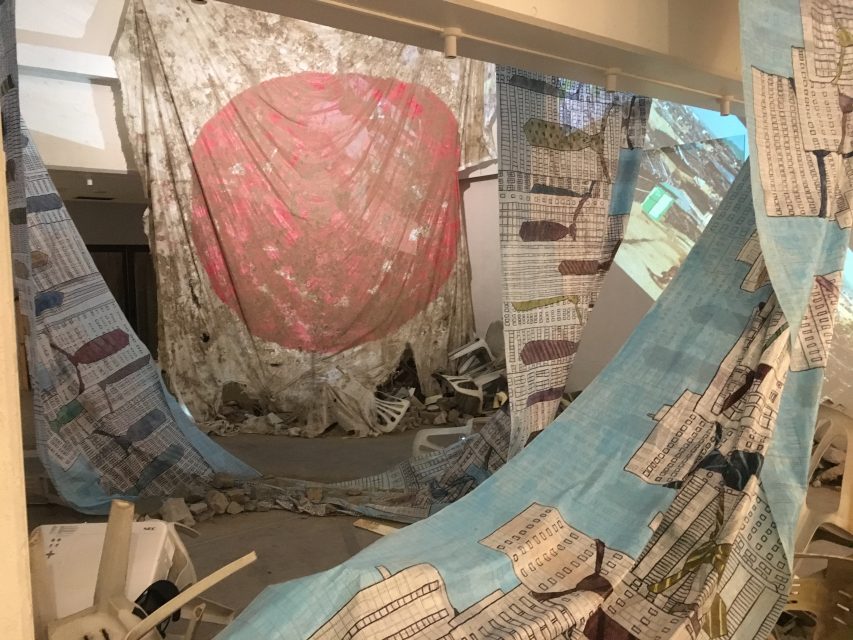

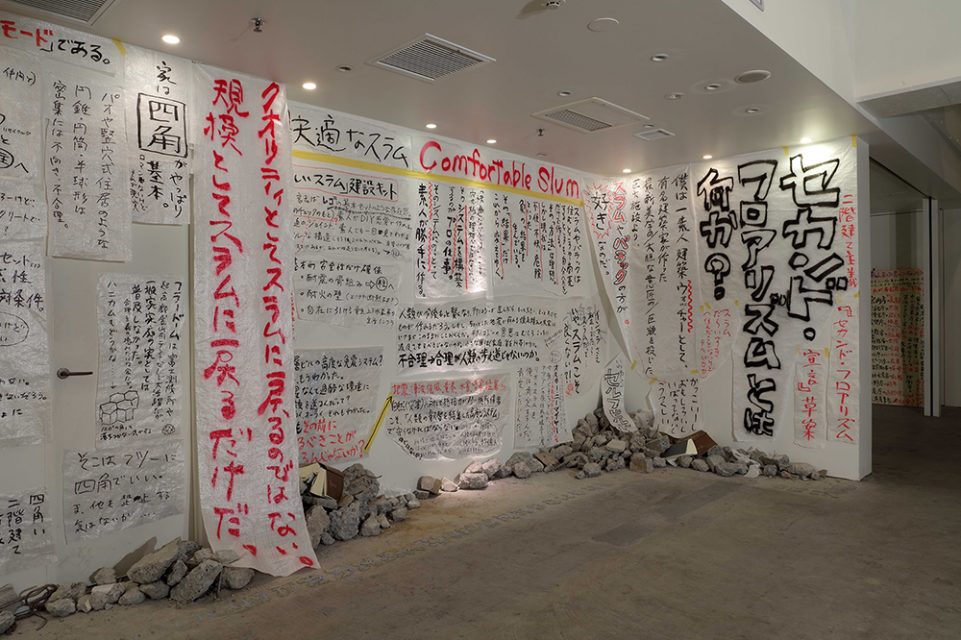

“Ground No Plan,” installation view, Aoyama Crystal Building, Tokyo, 2018. Photo: ART iT. All images: Unless otherwise noted, installation view, “Ground No Plan,” photo Kei Miyajima, © Makoto Aida, courtesy Mizuma Art Gallery, Tokyo.

“Ground No Plan,” installation view, Aoyama Crystal Building, Tokyo, 2018. Photo: ART iT. All images: Unless otherwise noted, installation view, “Ground No Plan,” photo Kei Miyajima, © Makoto Aida, courtesy Mizuma Art Gallery, Tokyo.

ART iT: We were just talking about your work Weed Cultivation and the organic way that shantytowns come together. In advance of the 2020 Olympics we are seeing more and more real estate development projects here in Tokyo, and it almost seems that as soon as an elderly person living in a single-family home dies, the land is sold and redeveloped into a multistory tower. The fabric of Tokyo’s neighborhoods is changing, and the land is being rapidly monetized by developers – with Roppongi Hills being the prime example of this. You have to pay a premium to stay there, and the people without money are treated as so many weeds to be cleared away.

MA: I did my show at the Mori Art Museum several years ago, and of course there are business connections between the museum and the Obayashi Corporation – and now I’m working with the Obayashi Foundation. In any case, I’ve never lived in a building that was more than two stories high, and the idea of living any further off the ground than that disturbs me, so although it’s mostly unconscious, that’s been the basis for how I’ve chosen my homes so far. I recently came to the realization that I only like living in two-story homes, and that informed this exhibition. I mean, I’ve never had the kind of life that would allow me to live in the properties handled by Obayashi Corporation and Mori Building, and it’s only through exhibitions like this that I can have any connection with them.

So should artists like me be grouped with the economic winners of the big corporations, or the low-income earners who get exploited? Now that I’ve started earning a bit, maybe I’m rising up somewhat, but until a while ago I was clearly on the bottom. Many of my peers and friends who are contemporary artists don’t make enough money to get by. In that sense, I guess I’m on the side of the low-income earners, or maybe a bit toward the middle.

With both the Mori show and this show, there may be those who were hoping for a more extremist angle from me and feel cheated that I didn’t bare my fangs and make works that directly critique those corporations. In fact, it was my decision not to go that far. As someone right about in the middle, who neither wags his tail nor bares his fangs at the big guys, I decided to avoid it as a theme altogether. Since I am clearly originally from the lower class, I thought it’s better to maintain that stance and engage with Obayashi and Mori without any posturing. It’s just that when I searched my heart to see what kinds of homes and neighborhoods I truly like, it turned out to be slums. That didn’t come out of some advance decision or conscious opposition to real estate developers. It just happened naturally.

ART iT: Although it incorporates heavy doses of humor and parody, your “2nd Floorism” manifesto seems to be calling for a new humanism in response to neoliberal capitalism.

MA: Yes, it includes the phrase “Change capitalism”! I was working on site, transcribing and arranging these aphoristic notes I had compiled in the memo app on my iPhone. “Change capitalism” wasn’t among the original notes, but as I wrote everything out, I started hearing this voice in my head saying, “There’s no way this could ever be realized.” I was going back and forth with myself about it, and then at the end I thought: “Capitalism right now . . . needs to change!” It just came out on the spur of the moment and wasn’t the conclusion I had planned. I definitely got a little heated as I was writing.

There are also the books of Japanese statutes – copies of the Roppou zensho – mixed like trash with all the junk in the installation. That also came toward the end of my preparations as I heated up and started thinking about things. Even though I’m just an amateur, I realized my proposal would probably be blocked under the current legal codes. In my head I understand the law as some exalted thing. Amid the accumulation of history, and all its conflicts and tragedies, law is like the aggregate of all our attempts to make things better, so of course I was thinking that for some punk-like artist such as me to denigrate the law is totally out of place. But I was gradually overcome by the desire to trash the law books. In the end art is about passion over logic.

Above: 2nd Floorism Draft Declaration (2018). Below: Installation view.

Above: 2nd Floorism Draft Declaration (2018). Below: Installation view.

ART iT: Well, from the initial design competition won by Zaha Hadid in 2012 to the more or less unilateral transferal of the project to Kengo Kuma in 2015, we’ve gotten a good view of the gangsterish behavior of the Japanese establishment over the course of the development of the New National Stadium for the 2020 Olympics.

MA: I’m also an amateur when it comes to architecture and architecture competitions, but unusually enough for me, I actually paid attention to the news about Zaha, and responded to it on Twitter, so it does relate to this exhibition to some extent. It got me thinking that the challenges people face in real architecture are no joke!

Then the offer came to do this project, and I decided not to do any research in preparation. I had the hunch that even if I just wanted to get a sense of the architecture world, it would be like stepping into a mire, and no good would come of it. I can’t say whether that hunch was right or not, but I decided it would be more effective to do the project as a complete amateur and barbarian.

ART iT: But is it even necessary to distinguish between experts and amateurs here? Everyone is a member of the same society. Don’t we all have the right to speak as citizens?

MA: Sure. So that’s what art is: speaking, giving voice – at least to that extent. Of course I think that experts are also necessary. Whether it’s an artist making an exhibition or citizens raising their voices through political movements or anonymous people posting to Twitter, it’s all the same – insofar as it shouldn’t be stopped.

ART iT: Let’s get back to Joseph Beuys. You’ve referenced him repeatedly over the course of your career.

MA: Yes. I guess I first got into Beuys sometime after the year 2000. I’ve mentioned it in a number of my recent interviews and tweets, but my rule of thumb is: “Most contemporary art happens in the triangle between Duchamp, Warhol and Beuys.”

In simple terms, when I was at university I leaned toward Duchamp, with the stance that I would say scornful, sarcastic things as if I were smart, and then by the time I made my debut at Roentgen Kunst Institut in the 1990s I had turned to Warhol. This was when Takashi Murakami also made his debut, so it was a time when we were using otaku images for all they were worth. Then what changed was that I did a half-year residency in New York, got married, and read a book on Beuys. I had some interest in Beuys as a person, but I was really more intrigued – in both good and bad ways – by the “Beuysian artistic ethos.” It might have been triggered by something I encountered during my stay in New York, or maybe my reaching middle age or becoming a father – I can’t say for sure.

Above: Artistic Dandy (2018), detail. Below: The video of a man calling himself Japan’s Prime Minister making a speech at an international assembly (2014).

Above: Artistic Dandy (2018), detail. Below: The video of a man calling himself Japan’s Prime Minister making a speech at an international assembly (2014).

ART iT: You seem to share some commonalities with Beuys. For example, we could say that you have become a guru for a younger generation of Japanese artists.

MA: Beuys came to Japan when I was at art college between high school and university, and then he must have died my first year at Tokyo University of the Arts. There was a Beuys boom among all the art students in Japan at the time. That’s when I first came to know of him. I was a little put off by all the fervor everyone felt for him, and had the reaction that he was just some old guy putting on an act.

ART iT: Do you think artists should not act like frauds or gurus?

MA: First of all, calling Beuys a fraud and guru was not my idea. I read in the book on Beuys that there were people in Germany who hated him when he was still living. He was charismatic, but for that reason he was also criticized as a fraud who talked big and took people in.

It’s beyond my expertise, but I guess it has some association with Jesus Christ and unique Euro-American views on charisma. I figure there’s some nuance that escapes me as a Japanese person who is not a Christian. I mean, in Japan there have also been charismatic religious frauds like Shoko Asahara. That kind of person can be found just about anywhere on a small scale, but there’s probably no religious concept in Japan of someone with such a massive charisma as Jesus. I feel that beyond the level of, say, a genius like Kukai, Japan does not have the conditions for a religion based on powerful individual popularity to work – and I think that probably extends to art, too.

ART iT: What about the emperor?

MA: With the emperor, where it used to be that the emperor was almost expected not to have any personality, now it’s all about having access to the emperor’s thoughts or whatever – which I feel is a bit different from how the emperor system originally functioned.

ART iT: So maybe instead of being a Beuys or a Christ figure, you’re closer to being an anti-Christ?

MA: I’d say so! I’m no guru. People like Chim↑Pom probably think I’m just a friendly old guy – easy to relate to, doesn’t get angry like Murakami. But I don’t have any charisma.

Although there are a number of reasons for it, in the end I think it’s basically because I don’t believe in anything too strongly. I can’t even give good answers to your questions. I’m just vague. It’s also in part because I’m stupid, but I’m not able to believe in something and talk about it head on. And I don’t want to be that way. I’d say my kind of personality is pretty far from charismatic.

ART iT: Do you think that artists do not need to take responsibility for their works?

MA: I try to take responsibility as an artist. Work. Responsibility . . . I think politicians who make promises during an election and then don’t keep those promises after they are elected should be criticized, but artworks are not the same as politicians’ promises, so the responsibility is different. What kind of responsibility should it be then? Regarding the works here, since I made them and exhibited them, and did it with commitment, let’s say that I take full responsibility for them.

Ape Graduate of the Oil Painting Department (2018).

Ape Graduate of the Oil Painting Department (2018).

ART iT: Looking at the Trump administration in the US, I’d say it’s the politicians who do not have to take responsibility for their statements!

The video of a man calling himself Japan’s Prime Minister making a speech at an international assembly (2014) is a good example of how you incorporate both right- and left-wing symbolism in your works, and always seem to take an ambivalent attitude toward politics. But in society today we are seeing more and more elements of the right and left intersect. For example, organizations like the Tea Party and many Trump supporters in the US see themselves almost as a kind of anti-elitist proletariat, and the political positions are getting confused. How do you view your own practice in light of these developments?

MA: I would say that, whether by intent or not, I’ve been confused ever since my debut. If I were to put it arrogantly – I mean, it is arrogant – but, well, what I might say if I wanted to be arrogant is: “The world has finally caught up to my confusion” – although that’s going too far. But, you know, if I wanted to sound arrogant, then I would say that I had a hunch all along that this is how things would turn out. The reason why is that from when I was younger I would intentionally do things like putting one foot on the right and the other on the left, and I also have the odd stance of critiquing contemporary art from inside the contemporary art world. It’s like I’m a double agent. I purposely sneak into the enemy camp.

Of course there’s no resolution to any of this. But it’s the same with the movie The Square, too. It doesn’t really have a resolution; it just ends. There’s a well-intentioned artist who wants to make the world better, and the contemporary art museum supporting that vision. The artist’s work is about “equality,” but even the museum exhibiting the work is far from equal. The film satirizes this kind of ambiguous, contradictory situation. Which is not to say that the artist in the film is a bad person, since she has good intentions, but actually – it’s complicated. I really sympathize with the film’s director. I think these problems will continue to arise, and that the positioning of contemporary art will have to change. I guess one change is that the film received a lot of attention in Europe and won the Palm d’Or at the 2017 Cannes Film Festival. It’s a film that warns us of the crisis that contemporary art has to face – which is a crisis I’m paying attention to, and as an artist I want to be working right in the middle of it.

It’s like, “It’s about time!” I was already going on about this crisis to my friend Tsuyoshi Ozawa when we were at art school together. How should I put it? Ozawa is a guy who loves art and still believes in it even now, whereas I always pissed him off by asking him how he could believe in art. But now my taunts are coming true. So that informed this exhibition – and the clearest instance of that is the Beuys karaoke video.

I | II

Makoto Aida: The Anti-Socially Engaged Artist