The work becomes a reflection of who makes it.

William Kentridge, a towering presence on the arts scene known for his charcoal and pastels ‘drawings in motion’, was born and raised a Jew in apartheid-era South Africa. A drama student in Paris in his younger days, Kentridge later went on to work with a company of puppeteers, and next year will stage Shostakovich’s The Nose at New York’s Metropolitan Opera. Yet he is more renowned as an artist. What drives Kentridge to supplement his theatre ventures with drawings, prints, and video installations addressing enduring questions of human existence? And why, in a world dominated by the likes of cel animation and computer graphics, does he remain wedded to simple frame-by-frame animation? We talked to the artist – visiting Japan for his first solo show in this country – about the ideas and experiences behind his creative endeavors.

Interview: ART iT

– You once mentioned an uncomfortable state for Jewish people living in Christian society South Africa. Can you explain what it was like for you?

It is not about being oppressed or about anti-Semitism, which I’ve never really experienced in my life. It’s more about understanding that one is not in the mainstream, that one is at the edges of the mainstream. It was a slight separation, but something that gave me a different perspective. As did having parents who were very involved politically: my father was a lawyer at the inquest of the Sharpville Massacre. There was the world as it was presented by teachers, or the state, or the school, and a very different perspective that I knew could exist as shown by discussions that my parents were having. So from an early age I understood a disjunction in the world.

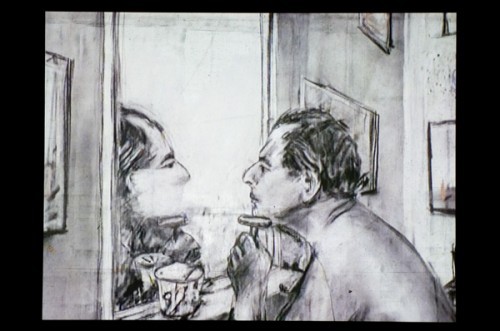

Video still from the animated film Felix in Exile 1994

Video still from the animated film Felix in Exile 19948min. 43sec. © the artist

– What do you think about the work of Jane Alexander, another South African artist from your generation?

Jane Alexander’s most representative work Butcher Boys – the three people sitting on the bench with the horns – is a fantastic piece. She did it as a student, and it’s one of the iconic images of that time in South Africa. I think she is brilliant with her photomontages; they are some of her best work. She also does some very beautiful installations.

– Even now that Apartheid and the Cold War are a thing of the past you maintain an interest in history and what’s going on in the world and stay abreast of current events. In your work your outer ego is reading the newspaper, but these days people don’t read the newspaper…

They read a screen. But sometimes you have to use an old technology to represent a current phenomenon. So for example, we no longer have switchboards that connect telephones manually, but a line connecting one thing to another, or one person to another, is a graphic representation of what is now an invisible technology. So some of the old technologies drawn refer to current phenomenon, like a newspaper rather than a screen.

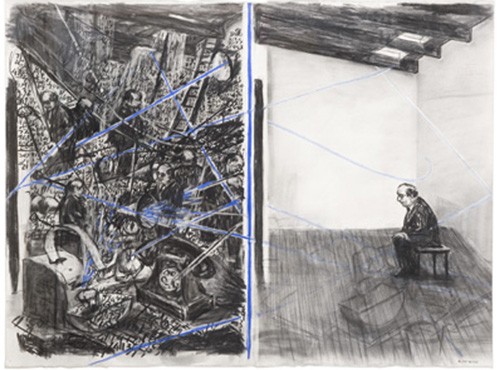

Drawing for the film Stereoscope [two rooms] 1999 © the artist

Drawing for the film Stereoscope [two rooms] 1999 © the artistAlways a will to make sense

– In an issue of ART iT [No. 18 – winter/spring 2008] we did about young Japanese artists, we used four key words to describe their art: white, shadow, floating and falling. These, especially falling, have been dominant characteristics of many works, not just Japanese, ever since 9.11, and yet your work featured them long before then. You apparently have a great many followers, not only in the West, but also in Japan and the rest of East Asia.

I know. I was rather astonished to discover that in China.

When we did our production of Ubu, which was about the Truth and Reconciliation Commission in South Africa, and then took it on tour in the mid-1990s, we first took it to Weimar in former East Germany. And there people said this piece is fantastic for us because we’ve got the opening of the police records and the Stasi files, we understand it completely, but we don’t think it will make sense anywhere else in Europe. Then we went to Switzerland on the tour, and people there said we’ve had all this questioning about banks and Nazi gold that’s been kept here, so this piece is fantastic for us, we understand it completely. And then we went to France where they were having Nazi deportation trials, and someone came from Bulgaria, and said this feels so local. So I finally understood that there are ways in which one brings one’s own history and puts it on top of things and finds connections. There’s always a will to make sense. So there is a way that things do connect, which is a surprise, but I’m pleased.

Still from Shadow Procession 1999

Still from Shadow Procession 1999Animated film and edited fllm from Ubu Tells the Truth 7 min. © the artist

There has also been around the world, and I don’t take credit for that, a huge explosion of animation as a form. There were no art schools teaching animation and now there are a lot of animation departments. And that’s partly because people can actually get jobs as animators afterwards. There’s an industry and the Internet is superbly designed for animation of different kinds.

Message for the younger generation

– I wonder about other images we see repeatedly in your artwork: cats, water, paper. Do these have any special meanings?

It’s not so much that they have special meanings. A cat is much easier to draw than a dog: one black charcoal line for the spine and a lot of marks around it, and it turns into a cat. Water because Johannesburg has quite a dry countryside around it so it’s nice to give it the water it doesn’t have. Paper sometimes for the passage of time. When you have a street photographed plain, it appears more like a still, but if there is a piece of paper flying down the street then you understand you are watching a street in time, that time is passing. Sometimes it’s a material for transformation: something gets covered by the paper. Its movement also has an innate jerkiness: as paper floats, it doesn’t just glide smoothly down, it makes a series of jumps. So even if you’ve got jerky animation, the paper still feels natural drifting down. The choice of what comes into the films are all a mixture of associations and practical questions, of how easy and flexible they are to do, and once they are there, they obviously have a set of associative meanings attached. But they often don’t start with the meanings; they start with the practical thoughts.

Journey to the Moon 2003

Live-action and animated film, 7 min. 10 sec. © the artist

– Thank you very much. Finally I’d like to ask you to give a message to our younger generation.

I suppose the first thing that was important for me was finding materials I could work with quickly and simply – not easily, but simply – like charcoal, like filming it myself. So that the work becomes a question of thinking aloud, rather than doing great technical preparations and then the thinking happens as a side issue. I think the films are also about agency, that they show how they can be made. It’s not that there is an extraordinary technology you have to learn before you can make them. It’s possible to want to make a film and start that day. And then whether it’s a good or bad film is not about the technology, it’s about who you are and what you are doing. It’s kind of naked. And if you’re a pretentious person, it’ll be a pretentious film. If you’re a stupid person, it’ll be a stupid film. It becomes a reflection of who makes it.

William Kentridge

Born 1955 in Johannesburg; graduated from the University of the Witwatersrand with majors in Politics and African Studies before studying Fine Art at Johannesburg Art Foundation. Internationally renowned for his distinctive animated short films dealing with subjects such as apartheid and colonialism, and for the charcoal drawings he makes in producing them, he also works in etching, collage, sculpture, and the performing arts. Since his participation in Documenta X in 1997, solo shows of Kentridge’s work have been staged in at museums and galleries around the world and his works presented at all the major international exhibitions. In 2009, he was named one of the world’s 100 most influential people by Time magazine. His survey What We See & What We Know at the National Museum of Modern Art, Kyoto runs through 18 October, travelling thereafter to the National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo (2 Jan – 14 Feb 2010) and Hiroshima City Museum of Contemporary Art (13 Mar – 9 May 2010). A concurrent survey William Kentridge: Five Themes, organized by the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art and the Norton Museum of Art (West Palm Beach, 7 Nov – 17 Jan) will travel to the Museum of Modern Art, New York (24 February – 17 May 2010) and select venues in Europe. He is currently working on a production of Shostakovich’s opera The Nose, to premier at New York’s Metropolitan Opera in March 2010.

ART iT Picks: William Kentridge: What We See & What We Know

ART iT Snapshots: William Kentridge @ MoMAK

ART iT Video: William Kentridge @ MoMAK

ART iT News: William Kentridge lecture/performance