The absurd as dislocated logic, which is the only way to make sense of the world.

William Kentridge, a towering presence on the arts scene known for his charcoal and pastels ‘drawings in motion’, was born and raised a Jew in apartheid-era South Africa. A drama student in Paris in his younger days, Kentridge later went on to work with a company of puppeteers, and next year will stage Shostakovich’s The Nose at New York’s Metropolitan Opera. Yet he is more renowned as an artist. What drives Kentridge to supplement his theatre ventures with drawings, prints, and video installations addressing enduring questions of human existence? And why, in a world dominated by the likes of cel animation and computer graphics, does he remain wedded to simple frame-by-frame animation? We talked to the artist – visiting Japan for his first solo show in this country – about the ideas and experiences behind his creative endeavors.

Interview: ART iT

– Let’s begin with your performance piece, I am not me, the horse is not mine, that you did here in Kyoto last night [4 Sept 2009], which like the opera you are staging for New York’s Metropolitan Opera for March 2010 is based on Gogol’s The Nose. You once said you thought you couldn’t be an actor, but in fact you are a very good actor…

I’m a very good actor if I do one role. Whatever role I do is the same as what you saw last night. No, I could not have survived as an actor, and for me it’s only possible to do the performance, which is acting, if I think of it as a lecture and not acting.

From I am not me, the horse is not mine

December 2008 rehearsal, Capetown

– It was very different from the version you did last year in Sydney. Is this the final evolutionary stage of the performance?

I don’t know. Sydney was the first. And when I saw the tape I realized it was much too manic, so it’s become calmer and has found a different rhythm. I want to do a second part with no words, just interaction with the screen. I’m interested now to put this one aside, and look at it again in ten years or so, when there will be quite a difference between me and the person on screen, so there will be a different kind of dynamic.

Interest in a strain of the absurd

– I’ve heard that David Elliott [Founding Director of the Mori Art Museum] was instrumental in your transition from the theatre world to the art world. Is it true?

David came to South Africa for an exhibition he was organizing on art from South Africa at the Museum of Modern Art in Oxford. I showed him my drawings, but he said he wanted to show my films, which until that time had been shown exclusively in film and animation festivals, and I was insulted! (Laughs) I thought, That’s rubbish, how can you show a film in an art gallery?! And so eventually I was persuaded to allow him to show them, and found I liked seeing them in an art context. I’m very grateful to David for making that push.

Installation view of 9 Drawings for Projection 2009

Installation view of 9 Drawings for Projection 2009The National Museum of Modern Art, Kyoto Photo Shikata Kunihiro

– Regarding your earlier theatre piece, Ubu & the Truth Commission, which was inspired by Alfred Jarry’s Ubu Roi: I read that you originally thought of doing Samuel Beckett’s Waiting for Godot but you gave up the idea…

I didn’t get permission. The estate that controls the copyright is very strict on how you can perform the play, and I wanted to do it with puppets and all sorts of things, so they said no. I was also working on Ubu images, and the idea came to try to put them together with Godot. But because I couldn’t do the Samuel Beckett, I had to find a text. And the text I found was the transcripts of witnesses from the Truth and Reconciliation Commission. Using the grotesque form of Ubu, and the archive witness testimonials as the text, I tried to see how close I could put the documentary and the kind of crazy world of Ubu together, and found I could put them right inside each other.

From Ubu Tells the Truth 1997

Animated and archival film, 8 min.

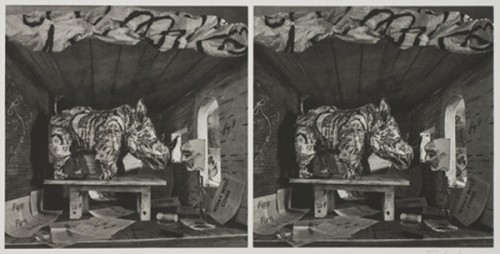

– Tell us about your reading experience in literature and plays. We see influence in your work from Franz Kafka, for example, and from some of the existentialist novelists and playwrights, and then the recurring rhinoceroses: are your fond of Ionesco?

I’d forgotten about the Ionesco rhinoceros. I actually acted in and directed The Bald Prima Donna when I was in high school. But when I started using the rhinoceros, and it comes through in many different images, I was thinking more of the famous Albrecht Durer rhinoceros and the rhinoceros of Pietro Longhi at the carnival in Venice. I was also a child in South Africa during the era when the white rhinoceros was facing extinction, and there were all sorts of programs for saving the rhinoceros. So it was a society in which they couldn’t save the people, but the animals they could.

Larder, from the series Underweysung der Messung 2007 © the artist

Larder, from the series Underweysung der Messung 2007 © the artistBut to go back to the subject of literature: I’m very interested in that strain of absurdist modernism which you get in Gogol as an early precursor. Not the absurd as just funny, but the absurd as dislocated logic, which is the only way to make sense of the world. And certainly the Beckett writing, which is not so much absurdist as a kind of strange depressive minimalism. Writers like Italo Svevo, the Italian writer who wrote Zeno’s Conscience in the 1920s, and of course Mayakovsky. That naïvely optimistic era of modernism, before it became cynical, for me is very important. But you are right in that a lot of the impulses for the drawings come from writing, rather than from other drawings.

Influence from other artists

– So regarding influence from other artists, you’ve mentioned Durer, Max Beckmann, and of course Goya…

There is the traditional history of modernism that went from the pre-Impressionists to the Impressionists to the post-Impressionists, coming through Japan with (ukiyo-e) woodblock printing, which reaches its apotheosis with Jackson Pollack in America. But there is obviously a place where it hives off, a figurative strain of modernism that goes through Impressionism and post-Impressionism, which includes Picasso and Matisse, but also Max Beckmann, which has a range of people who still hang on to a visual representation of the world in some form as the key to the image making. And that for me was the line that I was very interested in looking back at. I love a lot of abstract painting, but when I tried to do it myself, I didn’t know what I was doing. It became about look – did it look nice – which is a terrible basis to be an artist. In a way, I suppose now, with so much work in the world being photograph- and video-based, figuration and even narrative has become the dominant form; abstraction is a small side water.

Certas dúvidas de William Kentridge (Certain Doubts of William Kentridge) trailer

A documentary made in 2000 examining Kentridge’s art practice

– What about your contemporaries?

There are some artists I’m always interested to see what they are doing, even though my work is very different from theirs: Bruce Nauman for one. Anslem Kiefer was very important for me to see at one stage. Tony Cragg – I love the inventiveness of what one can do with sculpture. Seeing Dziga Vertov’s films for the first time a few years ago set off a whole change of thoughts for me of how one could work. Pistoletto’s sculptures at the documenta 12 years ago were fantastic.

William Kentridge

Born 1955 in Johannesburg; graduated from the University of the Witwatersrand with majors in Politics and African Studies before studying Fine Art at Johannesburg Art Foundation. Internationally renowned for his distinctive animated short films dealing with subjects such as apartheid and colonialism, and for the charcoal drawings he makes in producing them, he also works in etching, collage, sculpture, and the performing arts. Since his participation in Documenta X in 1997, solo shows of Kentridge’s work have been staged in at museums and galleries around the world and his works presented at all the major international exhibitions. In 2009, he was named one of the world’s 100 most influential people by Time magazine. His survey What We See & What We Know at the National Museum of Modern Art, Kyoto runs through 18 October, travelling thereafter to the National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo (2 Jan-14 Feb 2010) and Hiroshima City Museum of Contemporary Art (13 Mar-9 May 2010). A concurrent survey William Kentridge: Five Themes, organized by the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art and the Norton Museum of Art (West Palm Beach, 7 Nov-17 Jan) will travel to the Museum of Modern Art, New York (24 Feb-17 May 2010) and select venues in Europe. He is currently working on a production of Shostakovich’s opera The Nose, to premier at New York’s Metropolitan Opera in March 2010.

ART iT Picks: William Kentridge: What We See & What We Know

ART iT Snapshots: William Kentridge @ MoMAK

ART iT Video: William Kentridge @ MoMAK

ART iT News: William Kentridge lecture/performance