From the Mouth or in the Mouth but not of the Mouth – Words and Objects

By Andrew Maerkle

Installation view of Too Far to See (2011) at the Yokohama Museum of Art; ceramic, computers, projectors, speakers, mirrors; sound programming by Yuichi Matsumoto; video by Kotaro Konishi. All images: Unless otherwise noted photo ART iT.

Installation view of Too Far to See (2011) at the Yokohama Museum of Art; ceramic, computers, projectors, speakers, mirrors; sound programming by Yuichi Matsumoto; video by Kotaro Konishi. All images: Unless otherwise noted photo ART iT.Starting his career with the seminal performance group Dumb Type, Tadasu Takamine is known not so much for a particular style or practice but rather for the diversity of the approaches and media that he uses from work to work. This makes him difficult to characterize as an artist, although one recurring theme is Takamine’s investigation into the relations between body and mediation, expression and self-awareness. In essence, many of his works reflexively interrogate what it means to make art. His current solo exhibition at the Yokohama Museum of Art, “Too Far to See,” loosely focuses on Takamine’s activities of the past decade, providing an opportunity to evaluate the correspondences and divergences apparent in his recent output. ART iT met with Takamine in Yokohama to further discuss the exhibition and his works.

Interview

ART iT: In 2004 your video Kimura-san (1998) – which includes footage of you masturbating the physically disabled titular figure – was preemptively removed from the exhibition “Non-Sect Radical: Contemporary Photography” at the Yokohama Museum of Art, presumably in compliance with Japanese laws censoring the depiction of genitalia. The current museum director Eriko Osaka makes reference to this incident in her introductory message to your exhibition, while at the exit of the exhibition there is a hand-written wall text in which you discuss fellatio in terms of revenge. Is it possible to think of this exhibition as a kind of revenge with regard to the Kimura-san incident?

TT: No. The wall text that I wrote here, and its reference to “revenge,” comes from a work that I contributed to the group exhibition held in Amsterdam in 2009, “The Demon of Comparisons.” I was unable to show Kimura-san in 2004, and even given a solo exhibition that situation hasn’t changed; the work still cannot be shown. But I have tried to approach that context with a positive outlook. To begin with, the problem of censorship does not apply only to this museum, nor does it apply exclusively to museums in Japan. The simple fact that Yokohama was even interested in showing Kimura-san – and made an attempt to do so – is significant to me. I don’t blame the museum for the removal of the work. I think it’s more to do with problems with society in general. I previously exhibited Kimura-san at Ikon Gallery in Birmingham, England – thanks largely to the efforts of the director, Jonathan Watkins – but that doesn’t mean the work can be shown anywhere in England. More than categorically dividing everything into places where the work can or cannot be screened, I think it’s situational, which is something I anticipated when I made the work.

ART iT: Can you clarify how you understand the connection between revenge and fellatio?

TT: The origins of the text and thinking about the relations between fellatio and revenge begin with the work I made for Art Tower Mito in 2004, A Big Blow-job. When I was young I thought of fellatio as this unilaterally violent action carried out by the recipient upon the giver, although of course I came to understand that was not the case. But I wanted to further explore this dynamic between active and passive, giver and receiver, which I myself had experienced in caring for Kimura-san. As I worked on A Big Blow-job this image gradually took hold of me of a relatively small sex organ – not necessarily a penis – that is connected through the roots of the earth to the entire universe, and is melted down in the mouth of the giver. This I saw as a kind of cosmic revenge.

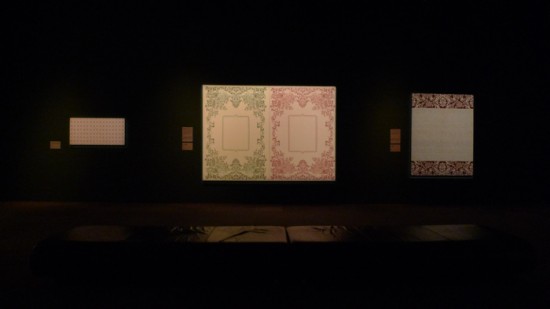

ART iT: I had thought that perhaps the exhibition as a whole was designed as an institutional critique. For example, the opening gallery features “paintings” made using found blankets that were stretched like canvases and arranged in the classical museum-style installation. At first glance it’s confusing whether you actually made these blankets, or simply found blankets that you stretched over painting stretchers, and this uncertainty is compounded by the “informational” wall texts, which delicately balance between seriousness and irony.

TT: Probably the critique of the museum is secondary to a critique of the audience. That gallery is basically a leftover from the Degas exhibition that preceded my own. The Degas exhibition was a huge success, attracting some 350- or 400-thousand visitors. When I went for my site visit there were an incredible number of people packed into the galleries, and although they could barely see the paintings, they all seemed satisfied once they had read the wall texts. I admit there’s something juvenile about such a critique, but frankly it could have been any Impressionist painter on display and people would have flocked to the museum. They like to see things that already have fixed values, and then talk about how great they are. The fact is that nobody really knows whether it’s great or not. They just read these authoritative wall texts and come away impressed. I wanted to take the piss out of this situation, so I asked the museum to leave that one gallery from the Degas exhibition for me to use, and then I inserted my own “paintings” and wall texts into the preexisting exhibition design. I chose to work with blankets because I see them as these daily essentials that are often treated without any consideration at all – almost the complete opposite of masterpiece paintings.

Both: Installation view of the exhibition “Too Far to See” at Yokohama Museum of Art, 2011.

Both: Installation view of the exhibition “Too Far to See” at Yokohama Museum of Art, 2011.ART iT: Also on display is your installation Sympathetic Trade (2005/11), comprising a video monitor flanked by two touristic photo-op-style figures clad in kimono robes with cutout faces, through which a synchronized audio track seems to poke fun at the action depicted in the video. Is this work also intended to parody the institutional mechanisms of art?

TT: The idea of incorporating figures alongside the video was part of the work when I first realized it in 2005 at the National Museum of Ethnography, Osaka, in the group show “More Happy Every Day,” only in that case I used African wooden figurines taken from the museum collection. Everything else remains the same, with the two voices commenting on the video as in a comic routine. The idea was to use objects from the museum collection that might become more interesting if they could speak.

I’m not sure what they were used for, but the kimono figures in the current version were simply what I found in the storage here. Rather than critiquing the museum outright, I tried to bring the museum and its staff into the making of the work as accomplices.

ART iT: What was your intent behind the soundtrack poking fun at the video?

TT: I suppose it’s a way of poking fun at myself. I shot the video sometime around March 1993 when I was in New York and had all these vague impressions of America that I thought could be turned into an artwork. I had a lot of footage from New York that I planned on editing, but because it was too challenging it all sat around until I was invited to the exhibition in Osaka. I decided to show this one excerpt of the footage as an example of my failed vision for the project.

ART iT: I thought the video alone was beautiful – at the time you had this willowy, elegant figure that suited both masculine and feminine clothing, such that the more outlandish your outfits became, the more they suited you; the voices that poke fun at the video seemed almost excessive. In that sense many of your works employ similar ironic mechanisms, as with the framing wall text that accompanies the video installation Do what you want if you want as you want (2001/11), in which you question whether you have created a work about friendship or a work about the situation in Palestine.

TT: Actually Do what you want is another failure. I first showed the work in 2001 at Kodama Gallery in Osaka. The previous year I had done a pair of three-month residencies in Israel for a total of six months over the course of a year. On my first visit to Israel I was introduced to a girl of mixed Saudi-German parentage who was raised in Germany but based in Ramallah in the West Bank. I was keen to visit Gaza so when I heard that she had relatives there I asked her to take me, and we became friends.

Half a year passed before my second visit. I contacted the girl to let her know I was coming, but all the Israeli people warned me that it was too dangerous to meet her. I disregarded these warnings, but in fact in the time since we had last met she had transformed into a radical activist. She could talk only about the situation in Palestine, telling me about people she knew who had been killed and other atrocities. She spoke English very quickly and it was difficult for me to follow, so most of the time I was in a complete stupor. As we had been filming our conversation, she then asked me to take the video with me outside of Israel and publicize its contents. I felt I had been entrusted with a task that should be carried out by a journalist, and as an artist I had no idea how to respond journalistically to the material she had entrusted to me.

I was mortified about the situation. When I had the opportunity to do the exhibition in Osaka, I thought I should go ahead and use the video, and ended up presenting it as a mosaic-style three-channel installation with each channel presenting a fragmentary viewpoint cutout from the original video. But of course the relations between the contents of what the activist says in the video and the act of appropriating that material for an art exhibition in Osaka were so skewed that soon after installing the work I felt it was a failure, and introduced the framing text panel as a complementary part to the video.

Top: Installation view of the work Sympathetic Trade (2005/11) at the Yokohama Museum of Art; figures, monitor, speakers; figures: “Representation of a foreign man in Japanese dress” and “Representation of a foreign woman in Japanese dress” (working titles), from the collection of the Yokohama Museum of Art, not dated. Bottom: Installation view of Do what you want if you want as you want (2001/11) at the Yokohama Museum of Art; monitors, DVD, video filmed on location in Jerusalem, 2001. Photo Tomoki Imai, courtesy Yokohama Museum of Art.

Top: Installation view of the work Sympathetic Trade (2005/11) at the Yokohama Museum of Art; figures, monitor, speakers; figures: “Representation of a foreign man in Japanese dress” and “Representation of a foreign woman in Japanese dress” (working titles), from the collection of the Yokohama Museum of Art, not dated. Bottom: Installation view of Do what you want if you want as you want (2001/11) at the Yokohama Museum of Art; monitors, DVD, video filmed on location in Jerusalem, 2001. Photo Tomoki Imai, courtesy Yokohama Museum of Art.ART iT: Do you have any guiding rationale or methodology for incorporating text into your works? For example, since many of your works originate from deeply personal experiences, do you conscientiously turn to text to provide a measure of reflexive distance from those experiences?

TT: It’s not the case with every work, but I do give consideration to how clearly language can explain my intents, or to what extent it can deflect possible misunderstandings. In particular the installation about my wedding, Baby Insa-dong (2004), was really addressed to my wife’s father, but I don’t think it would have communicated anything through only images and video. The text is what makes it an artwork. And again because Kimura-san has such strong imagery, when I thought about how to present it to the public I decided to integrate it into a performance, and then edit the video of the performance and overlay that with words. There was a process that flowed from image to performance to editing. Particularly in the case of such works in which I expose very specific, personal elements of myself, then I find language to be a useful tool for responding to potential misunderstandings – although it’s far from the only tool.

ART iT: Yet you also have multimedia installations like A Big Blow-job and Kagoshima Esperanto (2005) in which you explore the impossibility of communication by purposefully obscuring the text elements of the works.

TT: In the case of A Big Blow-job, the moving lights gradually reveal the characters that I have carved from the earth, drawing out the special texture of the text. Rather than having them listen to a narration or be fed the text through a video projection, I thought viewers would find it more interesting if they felt that they were discovering the text on their own. This in a way relates to Do what you want. I really can’t justify this comment, but I feel that what the activist was telling me was similar to anything you might hear on the news. At the same time the reality of the situation was different from any previous frame of reference I had in that I was witnessing a testimony, in a sense, from someone who was right beside me, a friend. What viewers of the work hear in the audio is real – not scripted – and exactly as it was related to me. What stressed me out was the idea of how to respond to or interpret this “reality,” to the extent that I was almost paralyzed. I think viewers of the work might experience a similar feeling. Eliciting that paralysis response is a major part of the work.

ART iT: The multimedia installation that concludes this exhibition and features video of silhouetted male and female figures fellating an assortment of phallic objects, Too Far to See (2011), was developed from a seminar in which a group of people exchanged their ideas on fellatio. Was there a difference for you in making this work as opposed to personal projects like Do what you want and Baby Insa-dong?

TT: The material in Baby Insa-dong is related to the social history of Japan but perversely I felt employing a personal viewpoint would be more effective in addressing such a topic. A discussion on the conditions of the Korean diaspora here is not something you can just leap into with a broad audience. It’s something you have to work through on your own, and I thought I could turn that process into a work. In contrast, had I executed it by myself the viewpoint expressed in Too Far to See could have been understood as an attempt to turn a personal obsession into a bigger discussion than merited. Carrying out the discussion in a group seemed to have more possibilities for interesting results, and I created an open structure with no fixed objective, allowing the work to reflect a variety of opinions.

Detail from the multimedia installation Lesson (Reconstruction) (2008), on view at the Yokohama Museum of Art, 2011.

Detail from the multimedia installation Lesson (Reconstruction) (2008), on view at the Yokohama Museum of Art, 2011.ART iT: This returns us to the final wall text on “revenge” and fellatio. Do you see that wall text as now being part of Too Far to See, or is it autonomous?

TT: The text – poem rather – is separate, although it forms the basis for the work. I distributed the poem to all the participants at the start of the seminar. The Too Far to See project should properly be considered an extension of the poem. The poem itself is vague. It discusses a utopia that is still far away. As such it considers how one might search for a way to approach that distant goal, not only through thinking on one’s own but also through the help of others – or even perhaps through assembling people together – and living through that process together.

Tadasu Takamine‘s work remains on view at the Yokohama Museum of Art in the solo exhibition “Too Far to See” through March 20. The exhibition then tours April 23 to July 10 at the Hiroshima City Museum of Contemporary Art and May 4 to July 17 at Ikon Gallery, Birmingham.