By Leslie J Ureña

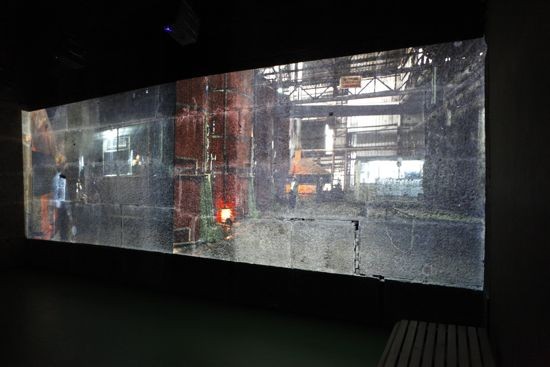

Music While We Work (2011), audio and video installation recorded on location in Huwei, Yunlin, Taiwan. Photo You-Wei Chen, courtesy Hong-Kai Wang.

Music While We Work (2011), audio and video installation recorded on location in Huwei, Yunlin, Taiwan. Photo You-Wei Chen, courtesy Hong-Kai Wang.Born in 1971, the Taiwanese artist Hong-Kai Wang works with sound as a conceptual means to investigate social relations and examine the construction of new social spaces. Wang is one of the participating artists in the Taiwan Pavilion at the 54th Venice Biennale, “The Heard and the Unheard – Soundscape Taiwan,” where she is exhibiting a new project, Music While We Work. Made in collaboration with Taisugar’s Huwei sugar plant in central Taiwan – one of only two such facilities remaining in Taiwan – this multichannel sound and video installation was produced with a group of retired workers and their spouses who returned to the factory to record a soundscape of the current employees at work. ART iT met with Wang to discuss her work in greater detail.

Interview

ART iT: For this year’s Taiwan Pavilion at the Venice Biennale, the subject is sound, variably defined. How do you define your contribution to this examination of “sound”?

HKW: My aim with this project was to set up a platform where the sound can speak for itself. The composer Edgard Varèse once reflected that people usually don’t know how long it takes for sound to speak for itself. In my practice, I often ask the audience to make the effort and to take time to engage in the act of listening, because to do so is political and because it instantly changes the power relationship between the listener and what was unheard and what is to be heard. In Music While We Work, I tried to push this examination further and perhaps make it more accessible by creating a platform where listening can be seen as a potential political agent in contrast to the visual referents of the social spaces that exist therein. What can be at stake when you are listening and after you’ve listened? This project is really about questioning and discussion while allowing oneself to be immersed in a particular architectural music-space.

Music While We Work (2011), audio and video installation recorded on location in Huwei, Yunlin, Taiwan. Photo You-Wei Chen, courtesy Hong-Kai Wang.

Music While We Work (2011), audio and video installation recorded on location in Huwei, Yunlin, Taiwan. Photo You-Wei Chen, courtesy Hong-Kai Wang.ART iT: What are the potential reactions that you think could emerge from Music While We Work?

HKW: This is a very big question. What this project will potentially instigate is a question to be asked maybe 10 years from now. Making artwork that is relevant is like calling for social change, and so is life itself, because they all consist of many small moves. One move is only meaningful if the next moves follow.

To respond further, what could be at stake needs to be asked not just by you or me, but also by many people who share similar concerns: for instance, the people who work in the sugar factory community or the people who share their work and experiences, or Bo-Wei, the political activist/composer who moderated the recording workshops for this project. What should we do in order to not simply react like one of Pavlov’s dogs, that is, to not react reflexively as conditioned by society’s attributes or even by the position we believe we have chosen?

ART iT: Did you have a chance to observe the viewers of the work in Venice? What were some of their responses?

HKW: It was a pity that I didn’t have much of a chance to observe the viewers of the work in Venice. But on my last day there, a woman of perhaps South Asian origin approached me and said that she really loved the piece. I didn’t know her at all, so that is probably the best kind of feedback I could have, because such a local situation based in my hometown somehow came across to someone from a very different cultural background.

ART iT: You don’t see the work as specifically political, but do you see it as political in terms of how it is produced? Did you consider the ways how political movements try to accomplish change?

HKW: What interests me is what could happen once one has an interaction with a project that insinuates something that does not occur in one’s daily life. The way I look at it is that this project brought an unusual situation to the people whose lives and work have revolved around the factory, and invited all of them to explore how to make/define a unique language through sound. When you read poetry, you don’t necessarily think about contributing to society. However, when you are making poetry, you are looking/listening for things you don’t see and don’t hear easily, and then whether you find them or not is a political process.

ART iT: You have a biographical connection to Huwei. Did you ever hesitate when deciding to make a work related to your birthplace? How did you separate your past from the work, if at all?

HKW: I’m always concerned that it could become too personal. Personal nostalgia is never interesting to me. To quote my mentor, Chris Mann, “Personal nostalgia is a mental illness.” To deal with this, I always try to seek out others who share similar life experiences or views.

You can never entirely detach yourself, however. In one way or another you always have an emotional and personal investment in it all. But if it can resonate with the audience, I don’t have a problem with that. For instance, when you listen to a love song, and it’s only about the singer’s loss of love, you can still relate to that, because you might share a similar experience.

I’m not afraid of my reference being specific, since I think that when it is specific, it also has the potential to be general.

Music While We Work (2011), audio and video installation recorded on location in Huwei, Yunlin, Taiwan. Photo You-Wei Chen, courtesy Hong-Kai Wang.

Music While We Work (2011), audio and video installation recorded on location in Huwei, Yunlin, Taiwan. Photo You-Wei Chen, courtesy Hong-Kai Wang.ART iT: How about the collaborators at the factory? How were they selected?

HKW: There was no selection from my end – I left my hometown when I was 15. I went to my father, and he was able to put me in touch with his former colleague, Mr Huang, who in turn enthusiastically put me in touch with all of these couples. He was extremely helpful and he did a lot of early coordination for me, in terms of the recording workshop. I then met with the couples last December, and of course Mr Huang was very charming and persuasive on my behalf. Because of my connection to the community, it was not very difficult to get them on board, and they all know my father, which also helped.

ART iT: How did you explain the project to them?

HKW: I told them it would be in Venice, though they had never heard about the Biennale. I think that they wanted to help because it would put the sugar factory in an international arena and, also, because what this project set out to do was very unusual to them. It’s not a TV interview, a movie, or a documentary. They just had to show up and learn to use the audio recorder.

ART iT: Were they increasingly curious as the production went on?

HKW: They were hands off. We were pretty much unsupervised. We went wherever, and had free reign of the factory and the fields. The whole factory was informed of the project by the management, so everyone was aware of our presence. From time to time people asked why we were still there, and why we were there at night. We would just tell them we didn’t have enough material, and that we were doing something different. The people at the factory are definitely curious about seeing the final product.

ART iT: Will you do a mini-recreation of Venice for them? How will you present it to them?

HKW: It depends on the type of spaces to which I have access. They have surely seen the newspaper reports, since the factory is likely keeping track of things. I think it’s important to get their feedback.

ART iT: You and your collaborators knew the exhibition would be held at the Palazzo delle Prigioni. Did that influence how you decided to organize the project? How did the project change from proposal to conclusion?

HKW: The building has very striking architectural characteristics. I didn’t think it would be necessary to cover the building, since the more you try to cover the Palazzo delle Prigioni, the more obvious this effort would seem. I thought that in this project it would not work. From a very early stage I decided the projection would be on the wall of the Palazzo. Fortuitously, the texture of the factory worked very well with the texture of the Pavilion. It was not a painful decision for me.

Installation view of Music While We Work in the Taiwan Pavilion at the 54th Venice Biennale, Palazzo delle Prigioni, Venice, 2011. Courtesy Hong-Kai Wang.

Installation view of Music While We Work in the Taiwan Pavilion at the 54th Venice Biennale, Palazzo delle Prigioni, Venice, 2011. Courtesy Hong-Kai Wang.ART iT: You’ve mentioned how the Palazzo’s rugged walls added texture to the piece. How about the space of the white cube? How would the exhibition of Music While We Work be affected by such a space?

HKW: Wherever this piece is shown, it has to deal with the space’s specific architectural form and its inherent spatial problems and properties.

I would be happy to see how it could be translated in the white cube, and how the pristine walls might affect it. We would need to consider how the audience would react to the projection, and the audio runs the risk of automatically becoming the soundtrack. I want to make sure that the audience pays attention to the sound, and that the projection is not privileged.

Since this project has to do with the community, I think in one way or another it has to go back to where it came from. The project has to be examined over time and across different places, so as to look into how this provisional intervention could still be relevant.

Hong-Kai Wang‘s work remains on view in the Taiwan Pavilion at the 54th Venice Biennale through November 27.