II. Homo sum, humani a me nihil alienum puto

Aesthetics and ethics, looking good is just not enough (2011), ceramic, display vitrine, plaque. A redesigned ashtray for Café Aubette by Theo van Doesburg (1883-1931) from 1927, from the perspective that Van Doesburg and Mondrian had never met. Photo © Keizo Kioku.

Aesthetics and ethics, looking good is just not enough (2011), ceramic, display vitrine, plaque. A redesigned ashtray for Café Aubette by Theo van Doesburg (1883-1931) from 1927, from the perspective that Van Doesburg and Mondrian had never met. Photo © Keizo Kioku.ART iT: We were just using the example of an Hermès glass to discuss how all objects can be understood as part of a universe of systems that shape the world, and how placing a given object in the space of art is a way to draw attention to its unique relationship to that universe. You have a work included in this exhibition, Aesthetics and ethics, looking good is just not enough (2011) – a reinterpretation of the 1927 Van Doesburg ashtray for Café Aubette in Strasbourg – which is in a sense not so dissimilar from simply exhibiting an Hermès glass, but you’ve also added your own intervention into the history of that object.

RG: I like that work a lot. It has only one place for a cigarette, whereas usually ashtrays have two or three because they go in the middle of the table. But in the para-possible view of the ashtray that the work represents, Van Doesburg never meets Mondrian, so it’s an ashtray for one person only. Van Doesburg designed the ashtray for Café Aubette, so it would have had numerous places for cigarettes because it would have been used for the café tables.

The story behind the work is that Mondrian was a painfully rigid formalist, to the point of being almost mentally ill. Van Doesburg loved Mondrian and his work but wanted to be more expressive and casual and try things out. The two had a bad argument and never spoke to each other again because Van Doesburg started painting diagonal lines, and Mondrian thought diagonals were wrong.

So I imagined what the reality might be like if they had never met. My ashtray is a realization of the existing ashtray, as potentially conceived by a Van Doesburg without the influence of the formal aesthetics of the overbearing father figure, Mondrian. So the letters are exploded across the design, because he’s free and liberated to go beyond the formal aesthetics.

ART iT: When you put yourself in the mindset of a para-possible Van Doesburg, is that different from making work as Ryan Gander, or any of the other characters you use to make work, like Santo Sterne or Spencer Anthony? What motivates you to explore these other mindsets?

RG: The thing is, if Van Doesburg had never met Mondrian, everything would be different. It would have changed the world in so many ways. We’re not even talking about wars or treaties or race issues or politics, we’re just talking about art, but the whole world would be different. So that line of thought is what lies beyond my version of the ashtray itself.

But a generalized answer to your question is that I hate doing the same thing again and again. I find it boring. I have lots of ideas, and I like trying different things and taking chances. It would be quite easy as an artist to make something, see it achieve success and keep repeating it, because then you would have money, people would know who you are, you would have a good job. But to me that’s not the point of making art. The point of making art is to try to compromise yourself and make something difficult and challenge yourself and push art history forward and make change. That’s really difficult, but it’s a lot more exciting.

So my love of making lots of different things is more easily realized if I’m lots of different people because then when I wake up in the morning I can choose to be any number of characters and start making work from that viewpoint. If I always start making work only as myself, it would be quite hard to change my mentality. We are human after all.

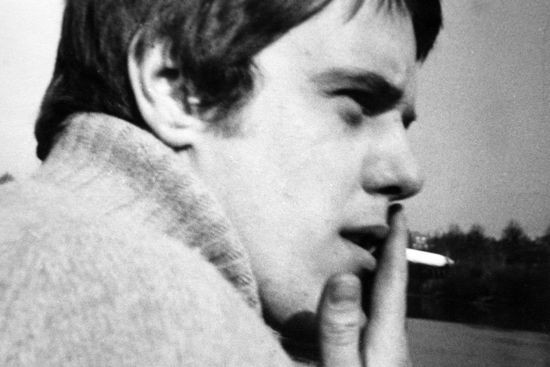

Portrait of Spencer Anthony Somewhere Between 1970-73 (2003). © Ryan Gander, courtesy the artist and Annet Gelink Gallery, Amsterdam.

Portrait of Spencer Anthony Somewhere Between 1970-73 (2003). © Ryan Gander, courtesy the artist and Annet Gelink Gallery, Amsterdam.ART iT: Does inhabiting other people’s possible mindsets also involve an element of self-critique – not only in the sense that you’re pushing yourself to do something that Ryan Gander might not be capable of doing on his own, but also in the sense that you have to keep track of the systemic relationships between these different characters?

RG: There are now about 12-15 characters for whom I have written character synopses, and who exist in my head: I know what they wear and what they eat for breakfast and where they live; some are dead, some are alive; they all have practices and each one has made a number of artworks, all of which look totally different.

Among those artists are two, Aston Ernest and Santo Sterne, who are really important for me, because one of them, Aston Ernest, is a better artist than I am, and one of them, Santo Sterne, is everything I hate about art. Their names are anagrams of each other, but one of them has all the characteristics that I love about artists, and one of them has all the characteristics I dislike. So I make myself make work that is better than I can make, and I make myself make work that I detest.

Making the bad art is easy, but living with it is difficult because you’re ashamed that you’ve made it. But that’s the work. The work isn’t the bad art itself, the work is me making bad art on purpose because there’s a higher reason than just the apparent result.

ART iT: Is the art that results from Santo Sterne a manifestation of the system of Ryan Gander?

RG: Yes, a wider system.

ART iT: This brings me back to the idea of hiding in plain sight, which literally appears in projects like the Locked Room Scenario (2011) and the “Alchemy Boxes,” but also is present figuratively in works like the installation of arrows embedded in the walls and floor of Taro Nasu Gallery that you made in 2010, “Ftt, Ft, Ftt, Ftt, Ffttt, Ftt, or somewhere between a modern representation of how a contemporary gesture came into being, an illustration of the physicality of an argument between Theo and Piet regarding the dynamic aspect of the diagonal line and attempting to produce a chroma-key set for a hundred cinematic scenes,” in which the title in a sense gives viewers everything they need to know for interpreting the work, without determining the physical experience of the work.

RG: Well, the title gives three possible interpretations of the architectural intervention. Beyond that, there are a thousand or more interpretations to it. If you’re an archer, you’d see that the arrows are cheap. If you’re someone who reconstructs historical battles, you’d see that they’re modern. It just depends on who you are. The three interpretations of the title are just a starting point. People could keep adding to the title in their own heads.

This idea of hiding in plain sight is interesting because it’s not me that’s hiding anything, the only things that are hidden are within the spectators themselves. It’s just whether they have the energy to go and find them. But that’s the point of contemporary art. It’s not about going to the cinema, sitting in a comfortable seat for 90 minutes with your mouth open staring into bright light and loud noise. That’s so easy, like being asleep. Art is meant to be difficult, and if it’s not difficult, it’s probably not good art.

Top: Ftt, Ft, Ftt, Ftt, Ffttt, Ftt, or somewhere between a Modern representation of how a contemporary gesture came into being, an illustration of the physicality of an argument between Theo and Piet regarding the dynamic aspect of the diagonal line and attempting to produce a chroma-key set for a hundred cinematic scenes (2010), installation view, Taro Nasu, Tokyo. Photo ART iT, © Ryan Gander and courtesy the artist and Taro Nasu, Tokyo. Bottom: Locked Room Scenario (2011), installation view. Image Julian Abrams, © Ryan Gander, courtesy the artist and Art Angel, London.

Top: Ftt, Ft, Ftt, Ftt, Ffttt, Ftt, or somewhere between a Modern representation of how a contemporary gesture came into being, an illustration of the physicality of an argument between Theo and Piet regarding the dynamic aspect of the diagonal line and attempting to produce a chroma-key set for a hundred cinematic scenes (2010), installation view, Taro Nasu, Tokyo. Photo ART iT, © Ryan Gander and courtesy the artist and Taro Nasu, Tokyo. Bottom: Locked Room Scenario (2011), installation view. Image Julian Abrams, © Ryan Gander, courtesy the artist and Art Angel, London.ART iT: I wasn’t able to see it in person, but what I understand of Locked Room Scenario is that it had a deliberate aspect of theatricality, with this elaborately staged exhibition that visitors navigated around but never actually got to enter. How is that different from the cinema?

RG: It’s completely different. A lot of people asked for their money back, because they couldn’t find anything, which is ironic because there were some 150 things and situations that had been fabricated that were there to be seen: fictional artworks, actors that came to give you something, phones that rang, people speaking in the toilets, dinner plans, dropped letters, crossword puzzles in newspapers inside windows. Visitors would get a text message two days before they even arrived, they were sent to a pub to talk to somebody behind the bar – and some people said they couldn’t find anything. It’s sad. It seems really crazy that somebody would want to go and see something, and would have the energy to catch the Tube to go to the place, and then when they got there they wouldn’t have enough interest or energy to even look.

Return to Index

Ryan Gander: Mobilis in Mobili