III. Timeo hominem unius libri

Matthew Young falls from the year 1985 into a white room (Maybe this is the way it is supposed to happen) (2009), stunt glass, window framing. Pieces of broken glass and sections from a window frame lie on the gallery floor, as if someone had fallen through a window with some force. The glass is made from stunt glass used in the film industry for special effects. The title refers to a fictional exhibition, “Sculpture of the Space Age,” mentioned in JG Ballard’s short story “The Object of the Attack” (1984). The exhibition was supposedly held at the Serpentine Gallery in the late 1970s, yet exists only as a title in Ballard’s short story. Installation view at Le Forum, Maison Hermès, Tokyo. Photo © Keizo Kioku.

ART iT: We were just talking about how there is a kind of disjunction in your works between the titles or concepts and how they are experienced, and how this disjunction actually lies within the viewers themselves. In this regard another work that strikes me is Matthew Young falls from the year 1985 into a white room (Maybe this is the way it is supposed to happen) (2009), with the pieces of shattered glass scattered on the floor. Particularly as installed at Maison Hermès, where it has an uncanny relationship to the gallery’s glass façade, the work itself is so physically spectacular that the title almost becomes irrelevant.

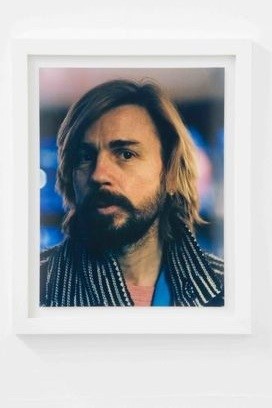

RG: Well, you need the name and the date, otherwise it would just be a dramatic effect. There are three types of work that I make, or rather three types of titles. There are titles that make the work easy to understand, and give you a way in, like Matthew Young falls…; there are titles that make things more poetic when the work itself lacks emotion or magic dust, like I don’t blame you, or When we made love you used to cry and I love you like the stars above and I’ll love you ’till I die (2008), which as the title of a bronze ballerina gives the work romance and irony, because it references the lyrics from a Dire Straits song; then there are titles like A portrait of Mark Leckey (2009), for a photograph I made of the artist Mark Leckey, which is a straight description of the work. With the latter type of work it’s important the spectator doesn’t know whether I like Mark Leckey, or whether he’s a friend, or a stranger, or if I detest him. It has to be open to interpretation. So those are the three types of titles that I use.

Matthew Young falls… wouldn’t function the way it does if the title were different. If it were called “Broken Window,” its longevity, in terms of the amount of time you spend thinking about it after you’ve left it, would be decreased. Different people have different measures for the quality of a work of art. Mine is not how much time you spend with the work but how long you think about it afterwards, or how many times you talk about it in a bar, or how many times you wake up in the morning and start thinking about it. I think that’s a good measure, because if a work stays in your head and grows there, it’s complicated enough that it can’t be interpreted simply.

ART iT: In that respect H (2011) would initially seem to be a straightforward title for a Plexiglas sculpture of the letter H, as inspired by the story Tintin and Alph-Art.

RG: I actually wanted to change the title to “Predator,” but the exhibition publicity has already been printed, so I won’t. When you look at the work with both eyes you can see it, but with a photograph, because a camera has only one lens, the work comes out looking like a distortion in space, which is exactly the same as the camouflage technology of the Predator creature from the blockbuster movie. That’s kind of interesting as well.

ART iT: Having read the Tintin series as a child, I never imagined that Hergé had this interest in art, or that he could imagine such a complex plot about contemporary art, with the Arabian oligarch planning a museum in the desert, and terrorists and cults involved in forging modern masterpieces, all of which has so many parallels to what we’re still going through today.

RG: Hergé was a genius. There could be so many books written about the visual devices he uses. It’s incredible.

He actually wanted to be a conceptual artist. He made abstract paintings, and I believe he took them to galleries in Brussels and tried to gain representation, but nobody wanted to work with him because as art his work just wasn’t very good.

H (2011), perspex. A large, Plexiglass transparent letter “H” sculpture as described by Hergé in the comic book Tintin and Alph-Art, as imagined by the artist. Installation view at Le Forum, Maison Hermès, Tokyo. Photo © Keizo Kioku.

ART iT: But does this work that you’ve made and which now stands in the exhibition space index all of this information, the story Tintin and Alph-Art, as well as Hergé’s own relationship to art?

RG: The work is an interpretation, because we didn’t know if the image that appeared in Alph-Art was Plexiglas until I made it – it could have been made of stone – and there wasn’t really a size to it, so I gave it a scale. It’s like the classic music video for A-Ha’s “Take on Me” (1985), where the comic book character comes out of the page and falls back into reality. It’s that process, but in a tongue-in-cheek way. But there’s the “A-Z” painting as well, which is the same thing. I like the idea that this exhibition could potentially have been all realizations of Alph-Art works. There are only two examples here, but it could have been great if the whole space were filled with works by Ramó Nash.

ART iT: The name even sounds like a character you would think up.

RG: Well, with Aston Ernest, Aston makes me think of Aston Martin, so he’s handsome and intelligent and kind, and he’s Ernest, which is like honest, but thoughtful, so quiet. Names are interesting to construct because they can give a sense of character without any other information. Ramó Nash is brilliant.

ART iT: In contrast your works have a strange relationship between name and actuality. Sometimes they’re disengaged or dislocated from what the name would lead us to expect.

RG: I like titles. I have a list of thousands of titles. I think of titles quicker than I think of works, and whenever I think of them I write them down, to choose from once I’ve made a work. Almost all my titles preexist the works.

ART iT: Do the titles generate the works?

RG: They have done. In some cases I wrote down the title and knew what the work would look like because of the title. A portrait of Mark Leckey is a portrait of Mark Leckey, and H an H – those titles come at the same time. But all the poetic ones, like In Spades, The Observatory, Remember this, you will need to know it later, I am Broken, they’re all preexisting, and were matched up with works at a later point.

ART iT: There’s this aspect of gesture and signification that you play with in specific works, yet at the same time I feel that you approach each exhibition as a work in itself.

RG: I love making artworks, but they’re kind of easy once you’ve made a lot of them and you understand a lot about visual language. If you make hundreds of artworks each year, there comes a point where you realize you can curate exhibitions from your own work, which is what I’ve been doing for the past five years, making exhibitions that look like group shows with works that are significantly different from one another but all share some thematic, curatorial construct.

There are actually three lives to being an artist: there is making artworks, which becomes easier the more you do it, although at the same time the easier it is the more challenging it becomes to make a challenging work; and then there is the curatorial stage, where you make exhibitions of your own artworks; and then there’s the practice, which is what I’m most interested in. The most difficult thing to do is to control the trajectory of your practice so that it is continually interesting, refreshing and surprising. It’s very easy to make the same thing your whole life.

Left: A portrait of Mark Leckey (2009). Image Jean Brasille, © Ryan Gander, courtesy the artist and GB Agency, Paris. Right: Installation view of “Icarus Falling – An exhibition lost by Ryan Gander” at Le Forum, Maison Hermès, Tokyo, with the bronze and mixed-media multi-component work The Observatory, or, it’s not that it’s bad, it’s just that you’re confused (2011) in foreground, and the painting “Scorning the abstract as an innate human device” Ramó Nash (2011) in the background. Photo © Keizo Kioku.

ART iT: At what point do you feel like you don’t know what you’re doing?

RG: Every day, all the time, because you become used to the feeling of not knowing what you’re doing, and you know this uncertainty in what you’re doing has been successful before, so it must be good to feel like you don’t know what you’re doing. I think if I made paintings of letters all my life, then I’d know what I was doing, and I wouldn’t be very good. That would be like working in a factory making the same thing every day. The whole point of wanting to be an artist was because I didn’t want to know what I would be doing every day.

ART iT: So you’re interested in breaking down the language of art every time you make a new piece?

RG: Yes – trying to.

Return to Index

Ryan Gander: Mobilis in Mobili