BETWEEN POTENTIALITY AND FATALITY

By Andrew Maerkle

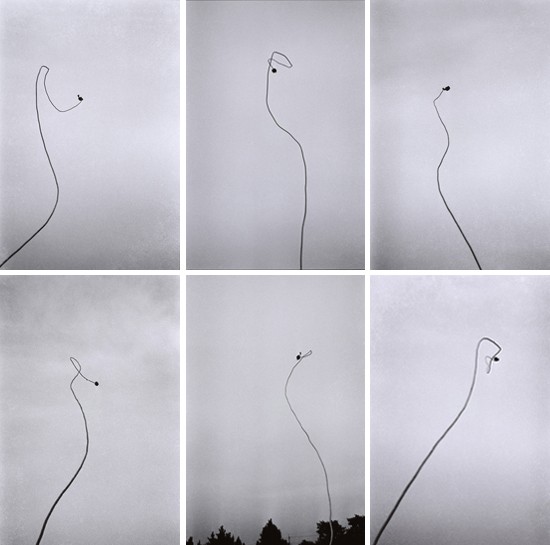

Kairitsu (1974), photo documentation of open-air work with stone and rope, Tama River, Tokyo. Courtesy Kishio Suga and Tomio Koyama Gallery, Tokyo.

Kairitsu (1974), photo documentation of open-air work with stone and rope, Tama River, Tokyo. Courtesy Kishio Suga and Tomio Koyama Gallery, Tokyo.Born in 1944, Kishio Suga was one of the key exponents of the group of artists active in Japan beginning in the late 1960s who came to be known as Mono-ha, or the “School of Things.” Using unconventional materials such as rocks, timber, sand and concrete, Suga created sculptural arrangements and interventions exploring the relations of potential between things as both objects and agents, or the way that all things, whether sentient or not, have the capacity to act upon each other, and in turn be acted upon. Articulating the tensions between visual and physical, conceptual and bodily modes of engaging the world, and underpinned by an inherently performative sensibility that extended to action-events held both in galleries and at outdoor sites, such works uniquely anticipated many of the concerns being addressed in sculptural practice today.

ART iT recently met with Suga at his studio in Shizuoka, where he was preparing for a solo exhibition at Tokyo’s Tomio Koyama Gallery, to discuss his career and artistic practice in depth. An accomplished writer who draws upon broad philosophical references, Suga began the conversation with an extended review of the development of his practice, presented here as an introduction to the interview proper.

Introduction

ART iT: In the current age of intellectual industry, the relations of dependency between people as well as between people and things are becoming increasingly invisible, or at least mediatized through digital screens and interfaces. Under such conditions it would seem that as a means of expression, sculpture is increasingly vital for understanding the physicality and consequentiality of the world, and I would say this is something that is prefigured in your practice from the very beginning through to today. Reflecting on your career, how do you understand this situation?

KS: First I should say that in the beginning I was not doing sculpture, if sculpture is strictly interpreted as a figurative practice premised upon the crafting of specific shapes.

I was basically the first person in Japan to consciously use installation as an expressive format. Prior to that, even if you happened to encounter something that looked like an installation, there was no real awareness of it as such. What was then understood as sculpture involved more or less predetermined materials like clay, plaster and iron, and those materials circumscribed the mentality of the practice. I understood this and wanted to avoid such a mentality altogether with respect to materials. But that left me with the question of what to do if I rejected the methodology of working with materials to create form. Of course, radical shifts in practice in the US and Europe such as Earthworks and Land Art or Arte Povera were being discussed in Japan. Nor was it only in the case of art, but indeed across diverse fields that this was a transformative period. Economic and political principles and values changed, as did perspectives on the world. So installation was what emerged from all these considerations.

Now, when we look at a space we can see that there are many things in that space, all with diverse values. But these things are not necessarily related to sculpture – they only become sculptural once you begin to handle them. Seeking to understand what was essential for me to develop my own practice, I continued thinking, looking and touching. Then I realized that in order to express this situation itself as an artwork, it would be necessary to interpose an action, but not one that was merely physical, rather one that could be spatial or even situational. This led me to the concept that an artwork can only be effective as expression based on the following three key factors: what is first fundamentally necessary is some “thing” – it could be anything, without any restrictions; what is next required is an awareness of the site where that “thing” is to be placed; and then comes an action that can establish a connection between “thing” and site, or in a broad sense enable the recognition of the connection between the two.

My primary concern after this was with how to position an installation in the gallery space. To that point you could simply bring something to the gallery, put it somewhere and declare it a work, but I was thoroughly opposed to that approach. I started thinking about what might happen if I brought things like rocks, wood, fabric, vinyl sheets, water and earth – which at the time were considered “natural elements” – into the fixed exhibition space of the gallery. I was thinking about what would happen if I brought nature into artificial space, which as such is itself figurative or sculptural, and how further interposing my own body into that figurative space to carry out additional sculptural processes there would raise even more, diverse problems for consideration, in that few of the “things” that I brought with me were actually appropriate to the gallery space. But it was exactly this displacement between space and “thing” that emerged as a mode of expression. Moreover, the level of displacement would differ depending on the “thing”: between wood and space, or rock and space, or water and space or fire and space, there were all differing implications in response to space.

For example, when you go out for a walk, you can see nature all around you. But if you are thinking sculpturally, upon picking up any element from the environment, you would no longer see it in terms of a totality, and rather must decide upon that thing’s individual value and significance based on the specific concerns it raises. And then, those differing values of significance would be linked together by your own actions. In other words, I was searching for the point of contact where the significance of the action itself, and the significance of the “thing” itself, could achieve a condition that allowed them together to become a form of expression.

Differing from traditional sculpture, which can only be completed in the figurative space of the gallery, discovering such a point of contact would allow all kinds of mentalities to become sculptural practice. This is because all things have multiple aspects. I am always aware that even if I use one side of an object figuratively, its opposite side must also be accounted for, because even if it can’t be seen, it exists. Any “thing” has both an obverse and an inverse, as well as a profile; an exterior as well as an interior. Looking at an object, you might not comprehend its interior, but actually it is precisely the interior that defines the exterior. So sculptural practice must also extend to thinking about the interior as well as exterior. In the case of a gallery installation, the part of a work that I most want to present would become the surface and be given priority in placement, but in actuality it is still necessary to communicate the presence of the inverse, profile and underside of the work. In other words, extracting the reality of a physical object is about making tangible its invisible aspects. The significance of how far to pursue this process changes depending upon the sculptural action, or the effect of the sculptural action, and that point of transformation is where you begin to elicit the corporeality of the “thing.”

In addition to making installations in galleries, I also carried out actions, which I called “events,” at outdoor sites and in neighborhood parks. I did this because I felt that the gallery space is not sufficient for extracting the reality of objects, or their specific materiality. If I showed one aspect of a thing in a gallery, then during an event, which might last from 30 minutes to an hour, I would use the same materials – like wood, rocks, water or cloth strips – and experiment with different ways of handling and interacting with them. Given a definite “thing,” my actions would reveal various aspects of that thing – in other words, its inherent multiplicity – while at the same time the thing itself would be destroyed and then reconsolidated through my actions.

Essentially it was necessary to take the thing apart by separating it out into its components, and then splitting those apart even further, as far as possible. Through this process one could appreciate the different elements and aspects constituting the thing. So the events were about expressing the reality of things by showing through action how we engage with them and how even something that ends up on display in a gallery undergoes some kind of process in order to arrive at that state of presentation.

At the events, the spectators would be standing around me, and even if I were focused on one thing, they would be looking in various directions and at different parts of the situation. At those moments when everybody looked at the same thing, I would try to show them what they were looking at. In that way the totality of the situation would become apparent. In other words, through the events I was observing how different people view things from different perspectives.

Index:

I. Perception – Frame

II. Action – Event

III. Abandonment – Occupation

Kishio Suga: Between Potentiality and Fatality