PROJECT FOR A MASQUERADE (HIROSHIMA)

By Natsuko Odate

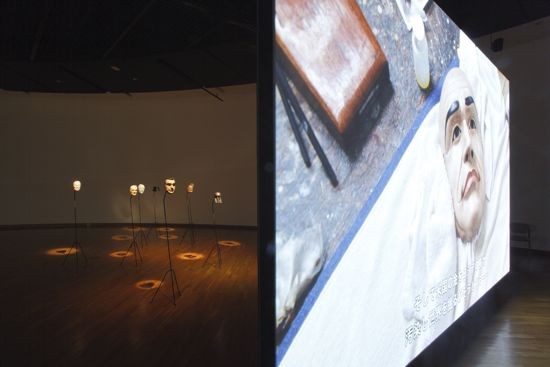

Project for a Masquerade (Hiroshima) (2010–11), with hand-carved Noh mask for the character Kichiji the Gold Merchant/James Bond in foreground and, from left to right in background, masks for the Hat Maker’s Wife/Anthony Blunt, the Hat Maker/Henry Moore, and the Innkeeper/Colonel Sanders. All images: Photo Keiichi Moto (CACTUS), courtesy Simon Starling and the Modern Institute/Toby Webster Ltd, Glasgow.

Project for a Masquerade (Hiroshima) (2010–11), with hand-carved Noh mask for the character Kichiji the Gold Merchant/James Bond in foreground and, from left to right in background, masks for the Hat Maker’s Wife/Anthony Blunt, the Hat Maker/Henry Moore, and the Innkeeper/Colonel Sanders. All images: Photo Keiichi Moto (CACTUS), courtesy Simon Starling and the Modern Institute/Toby Webster Ltd, Glasgow.In early 2011 Simon Starling’s Project for a Masquerade (Hiroshima) was unveiled in an eponymous exhibition at the Hiroshima City Museum of Contemporary Art. The project linked Cold War intrigue, James Bond characters and art history through the commissioning of a group of new masks for the Noh drama Eboshi-Ori (16 c), for which figures such as the British sculptor Henry Moore and the pioneering nuclear physicist Enrico Fermi were inserted into the traditional roles. The completed masks were then displayed alongside a film documenting their making.

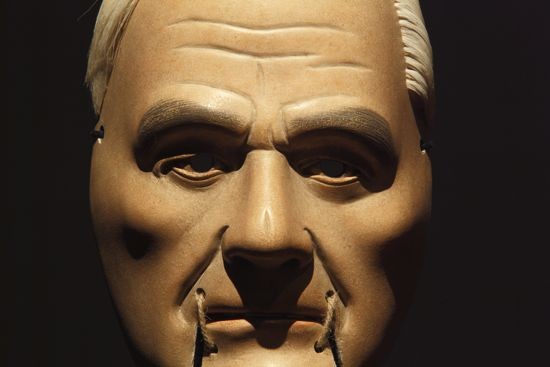

In Project for a Masquerade (Hiroshima), Starling tests the limits of two highly formalized expressive languages – Noh theatre and contemporary sculpture – through the delirious layering of multiple narrative relations among the objects he has created, simultaneously expanding and exploding their capacity for communicating meaning. For its ingenuity and delicacy in manipulating different cultural references, and its combination of sheer physical presence with deft conceptual subversion, this stands out as one of the most memorable projects of 2011.

As part of our year-end special issue, ART iT presents an interview with Simon Starling, conducted in Hiroshima earlier this year, as well as an excerpt of an artist talk with additional context about the conceptualization and production of the work.

Index

I. Interview

II. Artist Talk

INTERVIEW

Installation view of Project for a Masquerade (Hiroshima) at the Hiroshima City Museum of Contemporary Art.

Installation view of Project for a Masquerade (Hiroshima) at the Hiroshima City Museum of Contemporary Art.ART iT: It was very interesting to see the film and the masks for “Project for a Masquerade (Hiroshima).” When I first heard about the project concept, I anticipated the work would end up containing an element of exoticism, but you managed to create something entirely unexpected.

(SS): Yes, it was very important to do something different. When I started the project, I was quite happy when I visited the Noh mask maker Yasuo Michii in Osaka. Because mask making is a traditional craft, I had imagined he would work in an old, elegant Japanese house, but he actually works out of one room in a tiny apartment in a rather unglamorous part of town – the complete opposite of my expectations. And during filming it was really nice how the funny wallpaper gave everything a different atmosphere.

That was a good experience, because there is always a danger when you deal with historic material of falling in to the trap of exoticism. My work is about the mask making, but it’s also not about the mask making – it’s a device to tell the stories, in a way. I love this idea that Yasuo’s tiny room where the whole film was made becomes a portal into this global, historic set of events. It seemed like a good dramatic model for the film. It was also good that Yasuo is such a passionate baseball fan. The most exciting thing for him was making the Colonel Sanders/Innkeeper mask, with its underlying reference to the Hanshin Tigers, and going to Hanshin Koshien Stadium to make photographs of it. It was a nice hook to get him involved as well – he was understandably quite reserved when I first approached him.

ART iT: A major factor in the project is the idea of site-specific context, and the connection between Henry Moore and Hiroshima, and Henry Moore and the sculpture commissioned by the University of Chicago to commemorate the anniversary of the world’s first self-sustained nuclear chain reaction. What happens with this work when it is exhibited outside of its specific context? Can it still achieve a similar effect?

SS: Yes. I already showed the masks in late 2010 at the Modern Institute in Glasgow in an exhibition titled Project for a Masquerade (Hiroshima): The Mirror Room, conceived as a notional antechamber to the exhibition here in Hiroshima. There’s always this process of rethinking the projects every time they’re shown, and one of the nice things about making these bigger exhibitions is that you get to reinvent the older works in relation to the new works, so you can piece together a series of projects, which start to have different resonances when abstracted from their original contexts.

I’ve done quite a few works that have been proposed for one place and then ended up somewhere completely different.

Installation view of Project for a Masquerade (Hiroshima) at the Hiroshima City Museum of Contemporary Art.

Installation view of Project for a Masquerade (Hiroshima) at the Hiroshima City Museum of Contemporary Art.ART iT: In the works there is a kind of intersection or contact point between time and distance. Is that something that happens by chance or through design? What is the relationship between the temporal axis and the spatiality or physicality of the works?

SS: I don’t have a very structured methodology for generating the work. Of course it involves a fair amount of research, in the sense of sitting in libraries and reading books, but there’s also a lot of serendipity involved – accidents and collisions that happen along the way – and it’s just about having a nose for when those connections start to make sense, and hold two things in some kind of equilibrium for a moment.

Sometimes it’s a conversation in a pub, or even an article in an in-flight magazine. Projects evolve, and then one project evolves from the other. In a way, the Henry Moore project in Toronto, Infestation Piece (Musselled Moore) (2007/08), triggered these initial thoughts about Moore as a player in the Cold War and how he functioned in that situation. There’s a connection between the British art historian Antony Blunt and Moore in Toronto: Blunt was the man who initiated the first North American purchase of Warrior with Shield, by the Art Gallery of Ontario. But Blunt was also a spy working for the Soviets, while the zebra mussels infested the great lakes at the end of the Cold War, when the whole system broke down. These are the kind of absurd, fragile connections to which one has to give some sort of form.

I often discuss the idea that each work is a constellation of things that are spinning around each other. It’s a bit like the logos for the US Nuclear Regulatory Commission or the Atomic Energy Commission, with these atoms spinning around. It’s about making the gravitational force of the project strong enough to hold those things in some kind of orbit.

In the case of this current project, Yasuo’s craftsmanship is one of the things that cements everything together. The intensity of those masks as objects is extraordinary – they are amazing sculptures – and that somehow allows all the fragile links to hold, even though everything’s vibrating and could fall apart at any moment. Somehow the things have to be objects. Ultimately it’s still about making sculptures, about getting that right, and if it’s not right, then it doesn’t function.

ART iT: In general, as you start to visualize the material, how do you determine the form it will take?

SS: This is slightly disingenuous, but I think the best work makes itself. If the concept is right, then the rest follows: it’s about me not making decisions. That’s an oversimplification, of course, but I think there is an element of that. Things have to be the way they are, somehow.

If you go looking for something with a clear enough idea, everything falls into place. When I made the Moore piece with the mussels, I went to Toronto with very little idea of what I would do. I knew there was a big Henry Moore collection at the Art Gallery of Ontario, and I thought that might be an interesting thing to see. But before visiting the gallery I took a ferry to these islands on the lake where there’s a hippy commune, and on the ferry there was a bicycle that somebody had pulled out of the lake, completely covered in mussels. I thought, wow, that’s an amazing thing. Then later on in the day, when I went to the museum and saw Warrior with Shield, I suddenly realized, what if these two things can be made to collide? So it’s sort of thinking and not-thinking at the same time.

Detail of the hand-carved Noh mask for the character of the Hat Maker/Henry Moore.

Detail of the hand-carved Noh mask for the character of the Hat Maker/Henry Moore.ART iT: With your work on Moore it’s interesting because there is a kind of duality to it through the presentation of multiple realities. Yet although Moore comes off in a somewhat negative light, you seem to refrain from denouncing him.

SS: In a way, Moore is a surrogate for myself as an artist who has been confronted with similar problems and issues in navigating his career. I do not wish to portray him as evil or deceiving, nor do I wish to judge him, even though the project highlights a duality that is apparent in his work. We all make business-oriented decisions in our lives, and then balance those with ideological decisions; I do that, too. It’s just been a very fruitful way to continue my own investigation into site-specificity and context and thinking about how to deal with that in a critical way. I suppose I hope to problematize my own practice through looking at his. Of course, I’m completely colluding: I went to the Henry Moore Foundation in the summer and spent a week in their archives, and I’ve had significant contact with Mary Moore, his daughter. If what I’m doing is a critical practice, it’s also very much made from the inside.

In fact, there’s a very nice story that Mary Moore told me. She came to the opening of the exhibition in Glasgow, and there was this amazing moment when she met the mask of her father, which was installed at just about his height. She was quite taken aback, but she told me afterwards that her son, Gus, an actor and Moore’s only grandson, was in a BBC film about the bombing of Hiroshima, in which he played the bombardier who pressed the button. She sent me an image of Gus in this costume standing in front of a replica Enola Gay, and it was so strange to see. She was so excited to tell me this because she knows how crazy I am for these kinds of weird connections between things. It’s funny how these things grow when you put them out into the world, like a strange fungus or something.

ART iT: What is also impressive about the work is that despite containing such an amount of information, it avoids being didactic.

SS: For me it’s important that there are different levels of engagement with the work, and various ways to navigate it. You can go deeper and deeper into the project, but it’s important that there’s at least an initial phenomenological, direct, haptic experience, a touchy-feely experience of a “thing,” which you either take or you leave. And then that experience leads you to navigate what’s there and maybe sit and watch the film for 25 minutes or read the texts related to the different characters. Everybody comes to the work with a different knowledge and understanding, and of course there are aspects to which viewers will respond differently when it’s shown here as opposed to, say, in the US. The Colonel Sanders-Randy Bass subplot has a resonance here that it might not in Washington, DC, whereas the figure of Hirshhorn will immediately elicit some recognition in Washington and less so here.

To make work that is so heavy with information is difficult to pull off, but I think this time I’ve got it just right, given the balance between the film and the masks. I also like the idea that there’s no beginning or end. The masks are the end result, but they’re also a proposal for something that might happen in the future; the film that concludes the work is also a look back at how it began – it’s a rather unstable structure. Looking at it, you’re always thrown back on yourself.

I don’t know what is the work. It’s quite exciting to me that the work could be the play being performed in a temple somewhere, that it’s not just about the objects being on display. I like works that get tested in the world, that have a life outside the gallery space. That generates the aesthetic of the work as well. You make a mask in a particular way so that it can be worn for an hour-and-a-half-long performance. It’s stuff to be used and tested; it’s a kind of prototype.

Simon Starling‘s exhibition “Project for a Masquerade (Hiroshima)” was on view at the Hiroshima City Museum of Contemporary Art from January 22 to April 10, 2011.

Return to Index

Simon Starling: Project for a Masquerade (Hiroshima)