Since establishing his own practice in 2004, Sou Fujimoto has become known for innovative projects like Final Wooden House, a small bungalow made of stacked beams of lumber arranged so that the building’s architecture also functions as its furniture. Other built projects include the New Library and Museum of Musashino Art University – conceived as a spiraling “forest of books” – and Diagonal Walls / Group Home in Noboribetsu, which reconsiders the ways that walls can be used to modulate space. Fujimoto is also active in international exhibitions, participating this year in “1:1 – Architects Build Small Spaces” at the Victoria & Albert Museum, London, and presenting a solo exhibition, “Forest, Cloud, Mountain,” at the Watari Museum of Contemporary Art, Tokyo, in addition to participating in the 12th Venice Architecture Biennale, “People Meet in Architecture.”

ART iT met with Fujimoto at his offices in Tokyo to discuss the relations between the body and space, the creative potential of “landform” architecture and his experience working with artistic director Kazuyo Sejima in preparing his contribution to the Biennale.

IV. Ideas From the Body

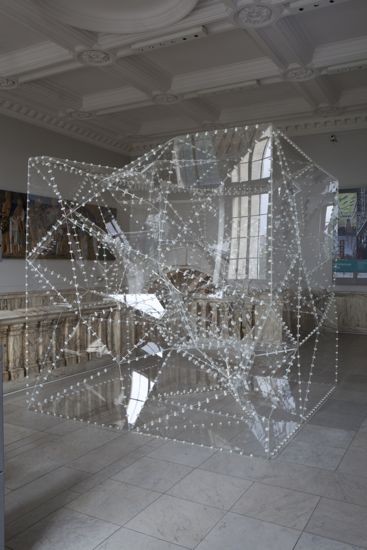

Detail of Primitive Future House as installed at the 12th Venice Architecture Biennale, “People Meet in Architecture.” Photo Yasuhiro Takagi for ART iT.

Detail of Primitive Future House as installed at the 12th Venice Architecture Biennale, “People Meet in Architecture.” Photo Yasuhiro Takagi for ART iT.ART iT: You are active overseas participating in exhibitions and giving lectures, and are included in this year’s Venice Architecture Biennale. I thought we could focus on this aspect of your practice. First, what are you exhibiting in Venice?

FS: My project for Venice, Primitive Future House, develops from about 10 years ago when I didn’t have any work and I spent all my time thinking about the future of architecture while groping towards an understanding of various archetypes through making models. The Primitive Future House series of models envisioned a residence for the future constructed out of step-like horizontal planes that would be suspended above each other at intervals of 35 centimeters, such that the planes comprising the structure could also serve as benches, or desks, or as shelving. I viewed this as a kind of indeterminate landform – a “cave” – that had been naturally generated, rather than as functional architecture.

At the same time, I was thinking about the scale of the body and how people interact with space, and how a space could possibly provide an impetus for people to relate to or communicate with each other. In the residence made of “steps,” users would become aware of their relations with other people or to the space as they thought about where to sit or how to situate themselves, and the environment could be more creatively enriching than, for example, a typical home or office in which everything is flat and behavior conforms to the orientation of the furniture.

Thinking about which phase of the study to bring to Venice, I felt that the most prototypical model would be best, because I wanted to directly communicate my investigation into the relations between the body and architectural space. I am presenting it at one-fifth scale, so including the display base the work stands about three meters high, and is made entirely of acrylic sheets with acrylic supports held in place partially by bolts. The acrylic has been cut pretty roughly, to give it a matter-of-fact kind of physical presence.

ART iT: Will people be able to enter the model?

FS: That won’t be possible. However, we thought it would be boring to simply create an object, because the most interesting thing about the project is how people affect the space. So we’ve created numerous figurines of various sizes and shapes that are placed in the model. The figurines are outlined silhouettes cut from metal, almost suggestive of line drawings. We’re fine with the possibility that the figurines could overpower the model, because the activities that people can do in the space are the whole premise behind the landform-style structure. We have taken the standard practice of inserting figurines into a model to an extreme, to show how the many ways in which people relate to space are actually what generates architecture.

Installation view of Primitive Future House at the 12th Venice Architecture

Installation view of Primitive Future House at the 12th Venice Architecture Biennale, “People Meet in Architecture.” Photo Yasuhiro Takagi for ART iT.

ART iT: Even though you are adapting a pre-existing concept, it sounds like your presentation in Venice complements the exhibition’s theme, “People Meet in Architecture.”

FS: I think it does. I had numerous discussions with Sejima about what kind of project to exhibit. We initially considered bringing to Venice a full-scale version of the bungalow that I made of wood, Final Wooden House, which also relates to the concept for Primitive Future House in that it is made of stepped wooden blocks that are each 35 centimeters in breadth. Later, we discussed presenting my House before House for the SUMIKA project in Utsunomiya, which has trees growing out of small, randomly stacked box-like forms resembling a hill, but it would have been impossible at 1:1 scale. Without belaboring her theme, Sejima provided me with many sketch-like ideas, and then we gradually worked toward a tight proposal. In that way, I think both the final project and the theme reflect consideration of how people relate to each other.

And the theme is not just about “meeting”; it addresses how people interact in unconventional situations. Theoretically people inside the “cave” structure must think about where to stand or sit based on the number of people sharing the space. In that sense when people meet, or when they engage with each other, architecture should be able to provide them with an array of options for different scenarios. If there’s a couple, then they can sit together in an intimate way, and if there are 10 people, then they can find another configuration. Maybe there’s a moment when you’re unsure what to do, but then you create your own solution, and start producing creative ideas in response to each new situation.

ART iT: Although you are participating in the exhibition, I’m curious to know whether objectively speaking you have any particular expectations for Sejima’s Biennale.

FS: I’ve never been to the architecture exhibition, and this is my first time participating, but I’ve always admired the event, or at least thought of it as a place where the most cutting-edge projects and ideas are unveiled. When Sejima told me that she wanted to include me in her Biennale, I viewed it as an opportunity to present to the world in a concise format my ideas of the past 10 years or more. Since my presentation addresses the essence of architecture, and the fundamentals of architecture, I hope it can stimulate many discussions with other people.

Installation view of Inside/ Outside Tree at the Victoria & Albert Museum,

Installation view of Inside/ Outside Tree at the Victoria & Albert Museum, London. Commissioned by the V&A. Photo © Sou Fujimoto.

ART iT: In general, what role do exhibitions play in your practice?

FS: That’s hard to say. For my current exhibition, “Forest, Cloud, Mountain,” at the Watari Museum of Contemporary Art (Watari-um) in Tokyo, I was once again reminded of the paradox that even though it’s an architecture exhibit there’s no way to display real architecture. With art, whatever’s on display is essentially as the artist intended. But with architecture, the real work is always someplace else.

As for the exhibition in which I participated earlier this year, “1:1 – Architects Build Small Spaces” at the Victoria & Albert Museum in London, I imagine the curators sought in some way to exhibit “real” architecture. But then the work becomes more of an installation as opposed to actual architecture. So it’s difficult. Showing a model and saying, “Look at this building I made,” feels lacking in some way, but simply exhibiting architecture as “space” also feels a little off.

ART IT: Until recently it’s been overwhelmingly the case that either you display sketches or models, or otherwise photo documentation of the buildings.

FS: Yes, it really seems that way. I think it’s still possible to communicate something through those media, but this exhibition at Watari-um has made me question whether those are the only means of communication. Where I am exhibiting models, I’m not displaying them only as an explanation of architecture. I’m also trying to convert into spatialized form the sense of how an architect integrates many different ideas into his working process. Visitors can look at things like arrangements of ammonite fossils, or arrangements of junk, and then suddenly encounter a large-scale, yet detailed model. In so doing they can obtain a physical experience of the leaps, links and sudden inspirations that all feed into architectural practice. I originally considered recreating a mock-up of my office in the exhibition space, but ultimately decided upon something that could better express the enjoyment of thinking about architecture, and the process of starting from one idea and then developing it into a new creation. A lot of architecture begins from a somewhat childish process of association.

Both: Installation view of “Forest, Mountain, Cloud” at Watari Museum of Contemporary Art, Tokyo. Photo Sakiko Nomura for ART iT.

Both: Installation view of “Forest, Mountain, Cloud” at Watari Museum of Contemporary Art, Tokyo. Photo Sakiko Nomura for ART iT.ART iT: As it has here, the word “model” also came up in our interview with Junya Ishigami, who described his project for Venice as existing somewhere between a model and architecture. What kind of potential do you see for redefining the concept of the model?

FS: What is interesting about a model is its completeness and its immediacy, or perhaps the way that it intrinsically combines a representation of both abstract composition and actual, physical experience. It is an incredibly rich medium. For example, using computer graphics you can create a realistic rendering of a building, but you can only see one image at a time, and then in order to understand how everything fits together you have to open another window with another image. You never obtain an integrated sense of the space.

Giving ideas some kind of physical presence is really important to me. No matter the project, I always make a 1:20 scale model. In that way, it’s there, and if I want to look at it I can see it, and assess different impressions of the design before deciding to bring it to the client. Even when I’ve already pushed myself to finalize a design, once I see the model if there’s something out of place I notice it right away.

ART iT: What do you think architecture can express right now?

FS: Right now even as the Internet and virtual reality continue to expand in our daily lives, I feel that built architecture has a value that will never be overwritten. Even though there is a physical limit to the amount of objects that it can contain, when I designed the Musashino Art University Library I realized that real space has an incredible density of information. It takes time to appreciate that density, but then gradually you begin to develop a physical means for accessing the information.

In particular, when we were building the library my concept was to create a “forest of books.” At first glance, a forest appears to be an arbitrary, incomprehensible landscape. Yet it is actually home to all kinds of animals, each with their own unique means of processing information that no other animal can understand, and it comprises all these pockets of distinct values. Then small markers or hints emerge as you grow accustomed to the landscape – for example, animal tracks – that serve as a guide to navigating it. The scope of your perception gradually broadens, and the idea that it’s all layered there in front of you is what is so profound about real space.

It’s like what I was saying previously about Primitive Future House, where there are all these different levels, and at first you’re not sure what to do, but then gradually as you use the space the landscape comes into focus and you find your own solution. What you see never changes and yet it is complex, so the longer you look at it the more you understand its significance. That’s what really interests me and that’s what I seek to realize convincingly through architecture.

Installation view of “Forest, Mountain, Cloud” at Watari Museum of Contemporary Art, Tokyo. Photo Sakiko Nomura for ART iT.

Installation view of “Forest, Mountain, Cloud” at Watari Museum of Contemporary Art, Tokyo. Photo Sakiko Nomura for ART iT.ART iT: In contrast to digital technology, as a medium of communication the exhibition itself is quite analog, and I wonder whether that might actually be the reason why exhibitions appeal to architects.

FS: I think that’s right. What struck me when I was preparing the Watari-um show is that exhibitions are not simply about transmitting information, but can also generate an experience. Even if you’re using models, you create a spatial dynamic based on how you install them in the room.

When Sejima and I first started discussing Primitive Future House, she told me she thought it would be beautiful if it were made of acrylic, but I didn’t want to stop at making a beautiful object. As I continued thinking about how to find a way for people to experience the space I had created, I had a shift in focus. I realized that even though making a less than full-scale model required substantial effort, I could intersperse figurines into that space. And although the final figurines that we decided upon are relatively close approximations of real people, what I began to realize is the fact that they are of a different scale than usual is extremely important, and my stance towards the Venice exhibition slowly become more apparent to me.

ART iT: This is a bit of an obvious statement, but in looking at your figurines for Venice it reminds me that architecture and people are intimately related. What is your understanding of “people”?

FS: I have a strong interest in the so-called “daily lives” of people. When they have a purpose, people tend to behave in a way that is fairly easy to understand. But when people spend a day at home, there’s probably no particular sense to their actions. I would like to find a way to alleviate that kind of daily paralysis. In other words, we tend to move in vague or almost unconscious ways, but probably on the level of instinct, there is an animalistic element or knowledge that motivates us. What I’m trying to do is amplify or elevate that extremely primitive human essence, not through a simple conformity to its needs but rather through a kind of stimulation. I want to make spaces that can activate our innate physicality.

Sou Fujimoto‘s work is on display in the 12th Venice Architecture Biennale, “People Meet in Architecture,” through November 21. His exhibition “Forest, Cloud, Mountain” continues at the Watari Museum of Contemporary Art in Tokyo through November 28.

Part I. Kazuyo Sejima: Activities, Environments, Sentient Space

Part II. Ryue Nishizawa: Societes, Landscapes, Building in Time