Neither decolorized nor faded – The latest color photographs by Daido Moriyama

(Part 1)

Daido Moriyama – Tokyo (2012) All images © Daido Moriyama, Courtesy of Taka Ishii Gallery and Office Daido.

Daido Moriyama – Tokyo (2012) All images © Daido Moriyama, Courtesy of Taka Ishii Gallery and Office Daido.We often say things like “a single photograph” or “a single photograph chosen by you.” But can “a single photograph” really stand alone? I am not talking about things like whether there is some context behind a photograph. When people argue that a photograph is never complete on its own, they usually bring up the matter of context. Recently we have witnessed a trend whereby someone photographs a lily, for example, and describes it as “a lily contaminated by radiation,” or photographs an intersection and declares, “Eight people died here when a car got out of control.” In other words, they introduce into photography the politics of captions. In contrast to this there is the approach described by Geoff Dyer in The Ongoing Moment, a book about American street photography that won the ICP Infinity Award for Writing on Photography in 2006. Dyer notes the extent to which Roberts Frank’s The Americans (although not Frank himself) references Walker Evans’s American Photographs as an example of the phenomenon whereby individual motifs and their arrangement – Talbot’s image of a scene with a broom leaning against a dark, rectangular doorway, for example, or his image of a ladder leaning against a haystack or the image of a man wearing a hat that appeared frequently in photographs taken before the war – appear in the work of later photographers without them being aware of it, almost like DNA. In other words, according to Dyer, photographs are taken, viewed and remembered in the context of other photographs. In fact, looking through dozens of collections of snapshot-like photographs, and in particular the genre known as American photography, it is surprising the extent to which the photographers shoot the same things over and over. Gasoline stands, utility poles standing in a row, signboards, letters, hats. Men loitering, desolate winter trees. Such is the extent to which various photographers seem to share the same photographic DNA that one wonders, Can they really get away with shooting the same motifs over and over?

The multiplicity of photography, or in other words the fact that multiple photographs potentially overlap in a single photograph, is what Daido Moriyama means by “memory.” Since Daido Moriyama: The Complete Works in 2003, there has been a succession of retrospective exhibitions and republications of past collections. Such confrontations with the past naturally cast a shadow over his new work. The first indication of this came with Buenos Aires (2005). With this photobook, Moriyama placed at the nucleus of his expression the state of affairs in which his past selves (of which there are as many as there are photographs he has shot) mingle with his present self (in the form of the finger pressing the shutter release and the eyes viewing the photograph). In a sense he was responding to light from the past, and backlit photographs arising from this filled Buenos Aires (the backlit photograph of the dog is typical.) Furthermore, a certain direction became apparent in the photographs that appeared in Farewell Photography (republication), Record no. 6 (republication), it, (2006) and Osaka Plus (2007), with Hawaii (2007) becoming the most focused expression of this. Any discussion of “memory” is inevitably accompanied by a discussion of personal reminiscences. However, unlike Shinjuku, Moriyama has no personal memories whatsoever of Hawaii. Having no memories of Hawaii he was able to take photographs of memories, because the photographs themselves remembered previous photographs – Hawaii was this kind of photobook, and in this sense it was a bold photobook.

“Memory” is not found in nostalgia, but involves a single photograph serving as an outlet for multiple groups of photographs. The photographic memories that have poured out of Moriyama these last few years point to the period of his reunion with Takuma Nakahira (1988) and the preparation of Hysteric No. 4 (1993).(1) This was also the period when Moriyama, spurred on by Takuma Nakahira’s comeback, was trying to get back to his roots and make a fresh start from the photo-sensitive exposure fetishism of Light and Shadow (1982), which he had immersed himself in after bidding farewell to modernism but not having discovered a new direction. This direction was further verified with the publication or republication of photographs from the past in Hokkaido (2008), Record no. 1-5 (republished, 2008) and A journey to something (republished, 2009). In other words, Moriyama is currently seeking to retrace a new past that is different from “hysteric,” and color is an important means of achieving this.

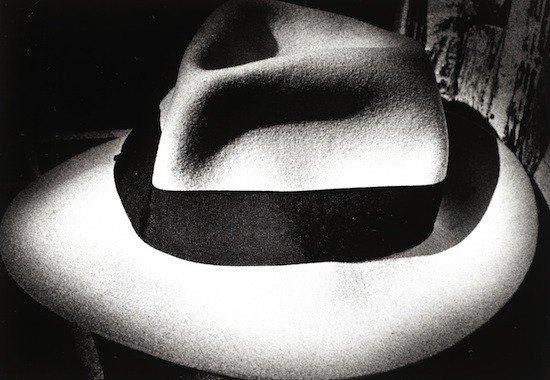

Daido Moriyama – Light and Shadow 4: (Hat) (1982), b&w print.

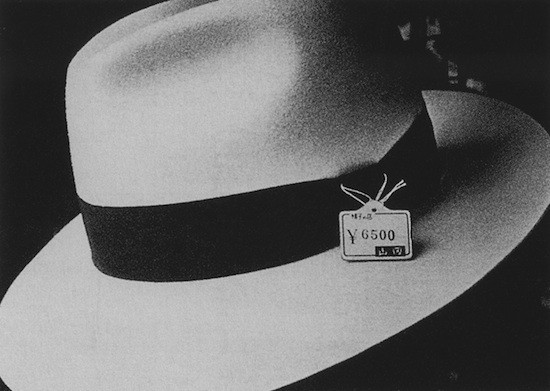

Daido Moriyama – Light and Shadow 4: (Hat) (1982), b&w print. Daido Moriyama – A Journey to Nakaji 2 (1984), b&w print.

Daido Moriyama – A Journey to Nakaji 2 (1984), b&w print.The first clue to understanding the latest color photographs by Daido Moriyama can be found in the dislocation he went through in the 1980s. This is plain to see if we compare, for example, the two photographs of panama hats with almost identical composition.(2) From an aesthetic photograph of an objet in which the shadows in the corners are black and the almost liquid white light oozes out to an everyday photograph in which a corner of the hat shop appears in one corner of the photograph and the price tag is clearly visible on the white panama hat. From a photographer who responds to the light emitted by the subject and abandons himself to the resultant “light and shadow” to a sobered photographer who captures sober everyday life as it is.

Daido Moriyama – New Japan’s Scenic Trio 1: Izu, Blossom Shade (1982), C print.

Daido Moriyama – New Japan’s Scenic Trio 1: Izu, Blossom Shade (1982), C print.The second clue is that in the past Moriyama’s colors were so-called “faded colors,” colors that were ravaged and faded from being exposed to light. Or to put it another way, Moriyama’s colors were gradations of exposure (sensitivity to light), which is to say they were a subtle grayscale, and in this sense his black and white and color photographs were the same.(3) His new colors are a breakaway from these “faded colors.”

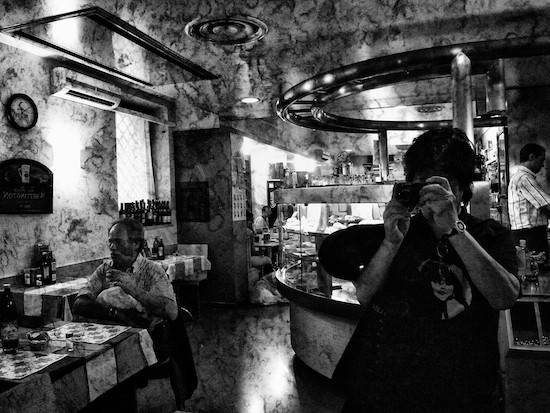

Daido Moriyama – From the series “Record no. 19” (2011)

Daido Moriyama – From the series “Record no. 19” (2011)The third clue can be found in Record no. 18 and Record no. 19 (2011). The latter, in particular, which depicts Tuscany with its glistening, hard stone surfaces and dry, black shadows, could almost be described as “Buenos Aires” without the “backlight.” As with Hysteric No. 4, the black is a deep black, but it is a lustrous, jet-black like the black hair of a Latin not the matt black that might be left on one’s hands by charcoal, making the photographs in Record no. 19 a tour de force. Among the main distinguishing features appearing in these works are a dynamic contrast, compositions in which the picture plane is divided boldly and collage-like compositions using posters, mirrors, and so on. Moriyama’s new color photographs share some of these features. But exactly how are sobered photographs that capture sober everyday life as it is, the breakaway from faded colors and collage-like composition connected to Moriyama’s new color photographs? (To be continued)

Both: Daido Moriyama – From the series “Record no. 19” (2011)

Both: Daido Moriyama – From the series “Record no. 19” (2011)-

For further information see Minoru Shimizu, “To Hawaii/From Hawaii” in Hibi Kore Shashin, Gendaishicho Shinsha, 2009.

- By this I refer to the gradual shift in Moriyama’s work throughout the 1980s, not to a particular dislocation between 1982 and 83. The culmination of his “light and shadow” phase was Lettre a St. Lou (1990).

- By this I mean that as a result of putting into effect in a forced way in the color world (the world of readymade hues) what he had practiced in the black and white world (oozing light) the colors ended up looking faded. This can be compared to the way in which the color photographs of the likes of Kühn and Steichen at the time when they began playing around with the Autochrome’s automatic color development, which was literally automatic, took on a faded appearance.