MOVING MONUMENTS

By Andrew Maerkle

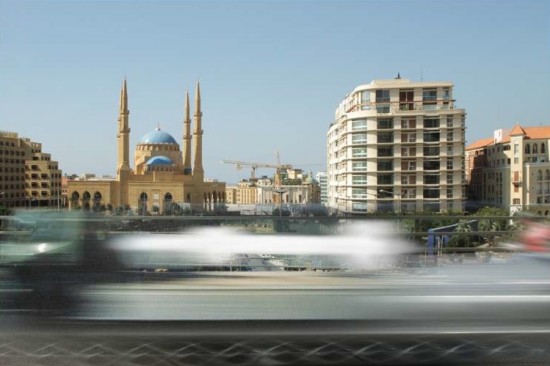

Restaged No. 7 from “Lebanese Rocket Society, Elements for a Monument” (2012), C-print, 100 x 72cm. All Images: Courtesy Joana Hadjithomas & Khalil Joreige.

Restaged No. 7 from “Lebanese Rocket Society, Elements for a Monument” (2012), C-print, 100 x 72cm. All Images: Courtesy Joana Hadjithomas & Khalil Joreige.ART iT: I’d like to start with the idea of circulation. You’re based between Lebanon and France, and participate in international exhibitions, while as filmmakers you are also involved in international co-productions in which the idea of circulation is in a way a condition for making the project. To what extent do you conceptualize or think about the circulation of the work as you’re making it?

KJ: This is a particular case for Joana and I in that we work together, and as such there is already a circulation from the beginning, ontologically. Collaboration is not just a place in common, it is a place to share and in which to participate. It’s not simply a matter of finding ideas that fit the concept, it’s also about understanding how my ideas match with her ideas and perception. Starting from there, the circulation gradually grows.

But our work always starts off from a specific location, by which I mean it starts from very personal issues that prompt us to react, think and work. For example, it could be some event in our lives. Then by starting to think about it and share it and evolve through it, the initial event extends into something bigger. As in the performance-lecture Aida, sauve-moi (Aida, Save Me), the personal experience [of dealing with a woman’s concerns over the use of her late husband’s image in the film A Perfect Day] becomes something we can share from Beirut to Japan and the rest of the world

JH: Circulation is important to us, but we don’t really consider it while we’re working. We don’t try to explain everything. We think of circulation more as an encounter. If a work can encounter others in a way that is interesting, it won’t be a question of geography. It would be a discussion of different ways of seeing art. If we can have the same concerns, the same interests, the same vision, it has nothing to do with nationality. Circulation has more to do with ideas, concepts. We think about it because we want an encounter to happen, but we never know where it will lead.

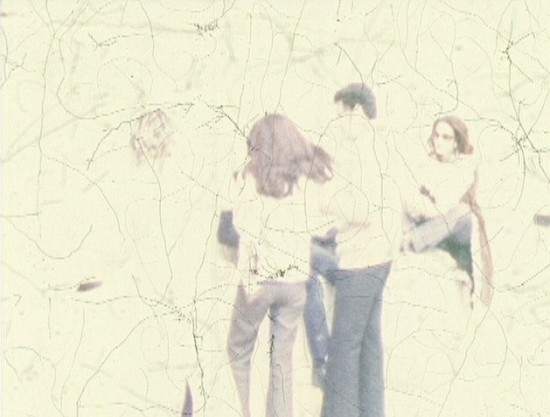

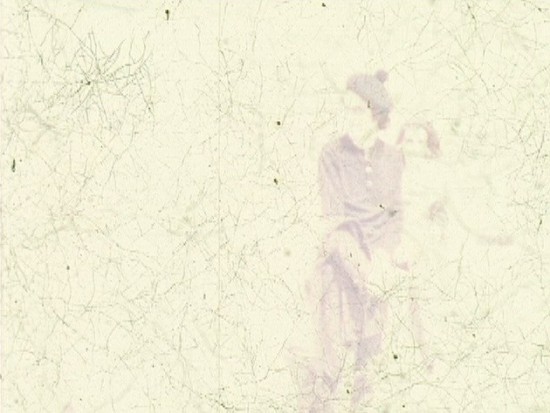

Both: Detail from 180 Seconds of Lasting Images (2006), Lambda photo print on paper, wood, Velcro strip, 408 x 268cm (4500 photograms, 4 x 6cm each).

Both: Detail from 180 Seconds of Lasting Images (2006), Lambda photo print on paper, wood, Velcro strip, 408 x 268cm (4500 photograms, 4 x 6cm each).ART iT: But in a work that uses found images like 180 Seconds of Lasting Images (2006), even though the source material has a deep personal connection to you, it also has a life of its own which you are now committing to a new kind of circulation. Do you think about these multiple layers of circulation that are taking place in the works?

KJ: With 180 Seconds of Lasting Images, we first worked on the Super 8mm film we found in my uncle’s belongings, a latent film that he shot before he was kidnapped and never had the time to send to the lab. We began with the personal history, but after that we went through a process of questioning the power of images, the feeling of images, the status of images. For example, how can a photographic installation represent the sensation of watching a Super 8 film?

This question is not solely linked to a personal story. It operates on several layers. Maybe you don’t know anything about the Missing in Lebanon but maybe you will first relate to the work from the issues relating to images, and then enter into the issues of Lebanon and our personal story. You enter the first gate and then you reach another one.

JH: When we found the film, we had been working on the concept of latency for several years. It’s not like we defined the concept of latency and then went out and did the work. We were working and then suddenly realized that there are certain links between the different works we were doing. It occurred to us that this kind of work has links with latency – maybe because at the time the Civil War had just ended and we had the impression that everything was still hot in a way, that there were ghosts around us, things not resolved, as if they had been swept under the carpet but were still there. This was what we wanted to show.

While doing all this work we started a script on missing people – an issue that is very difficult in Khalil’s family because his uncle was kidnapped during the Civil War and never returned, and his family were deciding at that moment whether to give up waiting. Then suddenly at that moment we found an undeveloped film that had been shot by Khalil’s uncle. Khalil asked himself the question for many weeks: Should I expose this latent film to the eyes of others or should I keep it as it is?

Finally we exposed the film and it went totally white. But when we did the color correction, some images appeared out of the whiteness, some lasting images were still there and this was incredibly moving. For us it was like a message, something that we could not keep to ourselves. We thought there were many layers to the work with relations to politics and missing people, personal issues and issues about images: what is an image, what do you do with it, how do you expose it, how do images keep the promises of the future and the past?

We first made a video based on the film, and then for 180 Seconds of Lasting Images, we had the idea of removing the video and putting all the frames of the film connected together into a single, composite image that would be very fragile. We scanned all the images and then we put all the printed frames on Velcro, so when you look at the installation you have the impression that they could fall at any moment. This was interesting to create an image that was made from film but also had the very fragile quality of something like a ceramic.

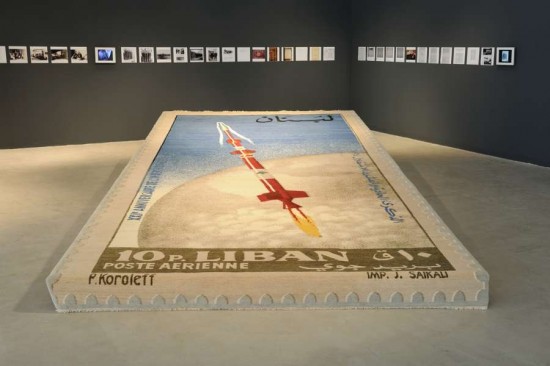

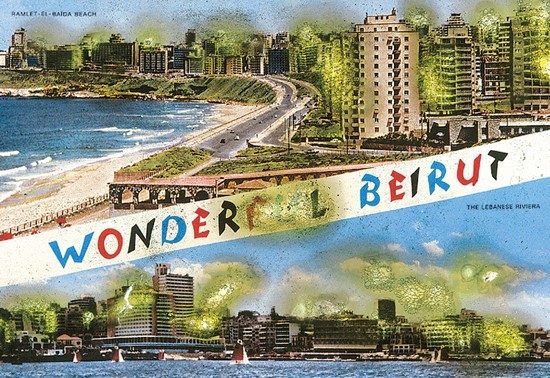

Top: Installation view of A Carpet, from “Lebanese Rocket Society, Elements for a Monument” (2012), hand-made rug, co-produced by Marseille Provence 2013. Bottom: Detail from Wonder Beirut – Postcard of War (1997), installation of 18 varieties of custom postcards.

Top: Installation view of A Carpet, from “Lebanese Rocket Society, Elements for a Monument” (2012), hand-made rug, co-produced by Marseille Provence 2013. Bottom: Detail from Wonder Beirut – Postcard of War (1997), installation of 18 varieties of custom postcards.ART iT: Do you feel that these are specifically images that are not circulating in Lebanon itself? And if so, is part of your motivation to make new images for circulation?

KJ: When we talk about latency, it is something that exists but cannot be seen. In other words, the conditions for them to be seen are not there. For example, if there is a problem with the imaginary, you might be confronted by an image, and see it without recognizing it. You have to know something to see it, and to see it you have to know it. There’s a relation between seeing and believing, which is at the heart of a work like the film Je veux voir (2008), or even the installation Wonder Beirut – Postcard of War (1997). How does this relate to the existing imaginary?

We are working now on a new project about the Lebanese Rocket Society. None of us were aware that a space rocket project had ever existed in the 1960s in Lebanon, even though it’s part of our history. We are talking about a project of 10 rockets that were conceived, produced and launched in Lebanon, and which made front-page headlines for 10 years – there were even commemorative stamps – and yet nobody remembers it. It’s like something that you cannot imagine anymore.

Similarly, one of our most recent works, A Letter Can Always Reach its Destination, is about the email scams circulating on the Internet. Many people believe in these scams, stories in which people pretending to be sons or daughters of known political figures have a big amount of money and need someone to help them to recuperate it in exchange of a share of the amount. And it is said that 200 million dollars are transferred every year in these scams, so they are efficient. The scams are always set in places where corruption is “possible” – in Africa, in Russia, in the Arab world, but never Europe, because nothing could really happen there for these people. What makes people believe in such a story? The scammers stick with an imaginary that is inherited from a colonial way of seeing things.

This is even a question of cinema. How do you believe in a film or not? This is the central question of our relation to images and a film like Je veux voir. When we had the idea of bringing Catherine Deneuve to Lebanon, we asked ourselves, what kind of character could she play so that we would trust in that character? It’s a question of the imaginary and of credibility. It’s a question of what kind of images you can embody, believe in and trust when you work in a specific context.

JH: I think Khalil is right to say that the images are there. It’s not that the images are not there – we are not “discovering” them. It’s like he says, there is a lot of memory, but how do you relate to this memory, how do you articulate it, what kind of history do you write with witnesses’ memories?

The discussion of the imaginary is very important. For example, the postcards are images that are visible in Lebanon, and they are more than visible in a way because they are an ideal image that we have to preserve and circulate of Beirut of the golden period of the 1960s. These images are “ok” to circulate. What we do usually is to see the images that are present and take them and switch them in another way. We took the images of the postcards and inserted signs of war into the images so that they become new “postcards of war,” and then put them back into circulation. This is another way of working with images that are there, by adding something to them that shifts the gaze or displaces the images.

On the other hand, the Lebanese Rocket Society is a project that people should have kept in the imaginary but did not. We don’t understand why it disappeared. So we just reveal what remains.

What we do is to work with images that are either personal or more collective and then reorient them. It’s like a puzzle. We try to put them together and make a history from them – because we work more on history than on memory.

Joana Hadjithomas & Khalil Joreige: Moving Monuments