Themes of life and death, past and future, everyday and festive.

A drive to produce art for the next generation.

Photo Nagare Satoshi

Photo Nagare Satoshi

We spoke to the artist selected to represent Japan at this year’s Venice Biennale about her approach to art practice, plus the background to her earlier works, and her latest project. Why a tent, and why an ‘all-female traveling troupe’? And what does it mean to exhibit at Venice?

Interview: ART iT

– Congratulations on being selected to stage a solo show at the Japanese pavilion in Venice.

Thank you. It’s a year now since commissioner Minamishima e-mailed saying he wanted to put my name forward, and time has just flown.

– I imagine your work is entering its most exciting phase about now (interview conducted in April 2009): can you start by telling us in your own words what sort of exhibit this will be?

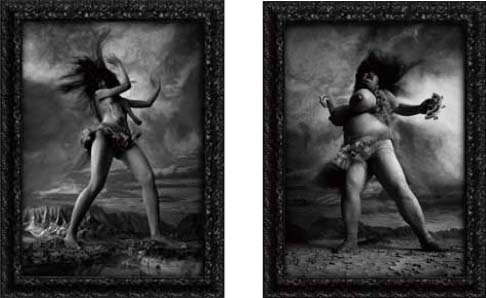

The title is Windswept Women, the subtitle The Old Girls’ Troupe. The exterior will consist of a new installation in the form of a black tent covering the whole of the Japanese pavilion, and inside, giant photo stands containing photo portraits of females ranging from young girls to elderly women, plus a small work on video. The motif is that of an exclusively female troupe traveling in a moving home, that is, a tent.

– Is this an extension of your Fairy Tale series, in which old women and young girls act out scenes from fairy stories?

Yes. Visually it’s connected to that image of women wearing a tent. The tent overlays the pavilion, and is designed to allow people to go inside. There’s a connection also in terms of the themes: life and death, past and future, the everyday and the festive.

– Where does your interest in tents come from?

I like the idea of movable homes, and groups that gather then disperse again. I always sensed something obstructive in the idea of a house that stays in one place, and was attracted to the notion of a home like that of (photographer and critic) Fujiwara Shinya, who was brought up in a ryokan (inn) where the distinction between family and guests was blurred, or (psychologist) Kishida Shu and (playwright and poet) Terayama Shuji, who grew up in the likes of variety theaters and cinemas.

At university I went to see Terayama’s films, and was deeply impressed by the spectacular last scene in Den’en in shisu (Pastoral Hide and Seek). Having returned repeatedly to a dilapidated house on Mt. Osore (in Japanese mythology, the entrance to Hell) to kill his mother, and ultimately failing to go through with the crime, the protagonist is sitting opposite his mother eating when suddenly the walls of the house collapse, and there they are, sitting smack bang in the middle of the heaving crowds of Shinjuku. I still adore the sense of exhilaration when that stifling room collapses and is exposed abruptly to broad daylight, that scene in which fact and fiction are turned upside down.

Empathy for the ‘exiled noble’

Yanagi Miwa Windswept Women 2009

Yanagi Miwa Windswept Women 2009Photo installation: five gelatin-silver prints 240x340cm (300x400cm framed) each

Courtesy the artist

– As you mentioned Terayama, tell us about the dramatic and narrative properties of your works.

Putting on a play is something I’d like to do. Whether art or theater, engaging in some form of expression virtually guarantees conflict with other people. The interesting thing about theater is that that conflict is sensed mutually, as pain. It is nourished by pain. That pain is sublimated in an overt manner, which is very healthy, and allows the audience to feel a sense of salvation. Of course art can do this too, but theater is more visceral, an instant fix, a dramatic panacea of sorts. Although at times I suspect it can work a little too well, and kill off the patient.

I love stage sets, costumes and the like, and as a student considered going down that path. When it comes to theater my tastes tend toward the vulgar, and I’m also fascinated by the likes of taishu engeki (working-class Kabuki) and opera, and the magical, celebratory foolishness of Fellini and his ilk. Although the festive nature of Terayama’s works is on the sentimental side, due in part to his Tohoku upbringing.

– You seem to have a liking for heroes that although not high-born in the sense of being royal or aristocratic, have an affinity with the Japanese literary genre of kishu-ryuri-tan, that is, the exile of a youth of high birth and their trials in faraway places. For example, Gabriel Garcia Marquez’s The Incredible and Sad Tale of Innocent Eréndira and her Heartless Grandmother, which you borrowed directly as a motif for one of your works; or Kirino Natsuo’s Grotesque, which you note is one of your favorite books. Kirino’s story is a tragic tale based on a true story, in which a woman raised in an elite family works during the day in a management job for a top company, and as a prostitute at night before finally descending to the level of a lowly streetwalker and ultimately, becoming a murder victim.

I wanted to be a manga artist, so as a student read a lot of comics. Tales of high-born youths fallen on hard times, as well as gender and age switching, were standard plots in Japanese girl’s comics. Back then the people doing girl’s comics literally lived from hand to mouth, scraping a living as writers and illustrators, and by the same token I think their readers were seeking stories to help them through life.

When I was chosen for the Venice Biennale, the first thing I did was re-read Morikawa Kumi’s Hana no Santa Maria (laughs). Although I don’t know if Morikawa actually went to Venice before she drew it. But girl’s comics in those days possessed an eager enthusiasm that rendered research on the ground unnecessary anyway. Mind you, the reality of Miyazaki’s animations, product of meticulous research in Europe by Miyazaki decades earlier, has had a major influence on our generation…

– Although one notes, not in your case…?

I just don’t care for the girls in Miyazaki films (laughs). At some point people started referring to his work as Japan’s national anime, the people’s anime, but I find the idea that children might be influenced by the extraordinarily maternal girls he chooses as heroines a little dubious. Parents need to explain to their children that those just happen to be the kind of girls Mr. Miyazaki favors.

– Science fiction is more your thing perhaps?

I’m not really that into sci-fi, but the devices used in it, time delay for example, can exert a certain appeal.

Recently I saw David Fincher’s The Curious Case of Benjamin Button. I was keen to do so because parts of the film looked like they might overlap with my own work, but I must say it was pretty grotesque. They lavished money and labor on it and made extensive use of special, meticulously detailed makeup, plus computer graphics combining body parts from several individuals to make a single actor to portray Brad Pitt’s character realistically from 80 year old down to teenager. These scenes, product of the herculean efforts of top special effects experts, were without exception just astonishing, in fact the whole thing was amazing.

It used to be that art supplied new visual effects, but now that role has been taken over by big-budget movies. But can this really be called a new kind of visual effect? The film was the total opposite to Fight Club in every sense.

– Are you a fan of Patricia Piccinini?

To be honest, I prefer Ron Mueck. He comes from a film technology background, and for that very reason is highly aware of narrative qualities and the power to entertain, making for some highly charged work. Not to mention the sheer size of his pieces. Although my work this time is quite big in its own right…

– Why so large?

No special reason. But it was inevitable. Big makes it look silly, like papier mâché. As far as making the family photos – crystallizations of time and memories – huge, that was an idea I’d kicked around for years, but for some reason I suddenly found myself again wanting to take something shelved for being just a little too ‘contemporary art’ and explore it devoid of any metaphor or symbolic substitution. I simply got the urge to make some large portraits of women.

A fear of the infinite and timeless

– To date your works have consistently possessed a strong narrative element, and in My Grandmothers and Granddaughters for instance, text plays an important role. Will text also feature in your new work for Venice?

Not especially this time.

– The word text is said to have its origins in ‘textile’ and ‘texture’. At the Kyoto City University of Arts you majored in weaving and dyeing: do you still have a thing about ‘weaving’?

When I was doing craft work I was using different materials and techniques to create my own peculiar layering and accumulation of detail, so I suppose it must have been there unconsciously. Even now I can feel suddenly emotional when surrounded by the stories of future grandmothers in My Grandmothers, or when the reminiscences of old women from different countries in Granddaughters join to weave a single tapestry.

– Foerster and Hans Ulrich Obrist in the catalog for your 2004 solo exhibition at the Deutsche Guggenheim, you speak of feeling “a very intimate connection to Kusama Yayoi’s ‘accumulation’ pieces”.

When I was a student, I ate and slept inside a sloppy sort of fiber piece I made myself. There was an almost hedonistic pleasure in the process: as I made the work I was buried in it, becoming intimate, fusing with it completely.

But then my ‘cocoon’ became suffocating, so I crawled out. This coincided with my graduating and going out into the world, and combined they had an effect not unlike being struck down with a heavy dose of the flu, rendering me unable to make anything at all for a while.

– In the same conversation you make a comment along the lines of finding time that moves linearly frightening, which is why, you explain, ‘in Elevator Girl time is frozen, and in My Grandmothers and Granddaughters time is circular’. You’ve also said you find ‘endpoints’ frightening.

Being infinite and timeless is actually rather scary. I’m not talking about time standing still, but the way a moment and longer time periods are connected, which to me feels really scary. I get this sensation of blocking, obstruction. When something is a story, it means a finite length of time. Because my knowledge of the origins and history of what is referred to as Western fine art, and of modernism, was grafted later onto a base of novel, movie and manga subculture, my work can have a certain ambivalence: relying on narrative, or contrasting and casting off.

– Did you have any wish to die young, or to be eternally youthful, or live to an especially old age?

I did have an early death wish from puberty through to about my early twenties, but that has disappeared completely. The idea of living to an old age appeals, but the reality of seeing off everyone else around me is not yet something I can relate to, so I’m not really sure. Aging is a cruel process no doubt, but I’m starting to realize that there are things you don’t understand until you get older. Which is fascinating, and it’d be a shame to die without knowing it.

When works that meant nothing to me when I was younger suddenly make perfect sense, I feel grateful to be alive. I find now that the penny has just naturally dropped with respect to art and films I diligently went to see, novels I read as a student but found incomprehensible. I’m now able to relate to the creators, to digest each one individually. That will only last to a certain age, before I lose that focus again, but I do want to live until I attain the most radiant of realms, although I know our life span is one thing that never goes the way we want.

– What is it that appeals to you about Abe Kobo, whom you mention as another of your favorite authors?

I suspect I relate to his chaotic mix of cold logic and I guess what you’d call his galloping pen, his obsession with the deviance of creating only to destroy. I suppose that penchant for Abe’s work is closely linked to my involvement with the theater. While making the tent piece for Fairy Tale I was reading two of Abe’s books: The Woman in the Dunes, in which the main character must dig continuously like a doodle-bug to keep her home; and The Box Man, in which a chap wanders around with a cardboard box over his head. In Box Man in particular, the writer of the novel switches several times in the course of the novel between subject and object, demolishing the narrative and making the book complex and difficult to follow. The box man lives with an electrical appliance box over his head, but in my work, it didn’t end up being a box. Ultimately it took the form of a tent, a house.

– Abe Kobo has a science background, and comes across as an emotionally cool sort of character. Could the fact that you like both him and the more emotionally expressive Terayama Shuji be a way of addressing two sides of your personality?

There’s certainly an ambiguity there, a struggle between those two aspects of my personality. I notice myself being sucked into some highly emotional, over-the-top world, then realize what has happened and beat a hasty retreat.

The desire for an alter ego, and matters of life and death

– It seems to me you desire to be more than one person. The photo book Fairy Tale contains a dialog with Nona Tokue Pizan, ‘a writer born in Shanghai in 1924’, but this was later revealed to be a dialog with one person – you – playing two parts.

Christine de Pizan was a woman of letters in medieval France said to be the world’s first professional writer and feminist. The other names belong to my grandmothers, and I combined them. I made my Pizan an elderly woman running a private library.

– Those close to you know that your soft toy ‘Usako’ is the master, or rather mistress, of the house.

Like Nona Tokue Pizan, she’s really a sort of grandmother. She’s been around since I was born, and resembles a Shinto relic, so I call her ‘Usason’ from ubason shinko (worship of Buddhist deities in the form of elderly women known as ubason). She’s contrary and malicious, like a yama-uba (mountain crone) or datsueba (hag who strips the clothing from dead souls who fail to bring money to pay for crossing the River Sanzu [equivalent of the Styx in Western mythology]). I always answer in good faith, but she outfoxes me every time.

– Does she offer up the occasional divine message?

She’s less into divine messages and more into berating me relentlessly. Even when I went to the Venice Biennale previously, every time she would ask sarcastically why there were none of my works there…

– Is Usa-chan an influence on your work?

Usa-chan is of a classical bent when it comes to art, and is one of those who find contemporary art a complete waste of space. I explain to her why I make things – she of course doesn’t understand why such things are necessary – but she refuses to have a bar of it. In some cases that actually leads me to modify my works.

– Do you make them for Usa-chan?

That’s right. Creating art for Usa-chan offers a kind of personal salvation, is for art itself too, for the grandmothers that raised me, and for the next generation. Speaking of which, I’d never thought about the next generation, but I’ve begun to recently.

– Is that because you’ve had a child?

Becoming directly, viscerally involved in matters of life and death does throw you into the temporal flow of life. Until then after all, I’d done nothing but work on my art, essentially living the same life I did as a student. And Usa-chan never ages. When you have an elderly person unable to do today what they did yesterday, or the opposite, a child able to do today what it couldn’t do yesterday, it gives you an intimation of the limited span of human life, and the passing of the generations.

I have very little memory of the people who spent lots of time looking after me as a small child, but I imagine it was my grandmothers. It’s only now I realize just how much of their precious remaining time and stamina they gave to me; and how each of us is a product of accumulated time passed doing nothing in particular, time that does not stay in the memory. Imagine, I used to find artists who said that sort of thing a bit suspect (laughs).

– This new work of yours deals with women of age groups that have not appeared previously in your work, ranging from young girls to elderly women, just excluding babies. Is this also due to this change in outlook?

In the locked-room dramas of my previous series Fairy Tale, a realm is repeatedly created consisting solely of the polar opposites of youth and age, the extreme ends of life, skipping over the middle. When I did that work, the ‘four sufferings’ of Buddhist belief – birth, aging, sickness and death – existed for me only in a sort of fantastical fog, while I myself lived timelessly. Everyone who makes art has the intensity of an Art Brut-like eternal youth, of sailing through a timelessness harboring a childhood sense of omniscience. The audience too expects that. But that sense of ease vanishes in inverse proportion to the increase and elevation of one’s works.

Which is perfectly alright, in my view. Works that never change, works devoid of set- backs, where energy and motivation never flag, hold minimal interest for me. Better to somehow eschew the established path each time. Aging and dying are rapidly becoming reality to me now, and I suspect the idea of ‘giants of women striding the land, feet planted firmly on the ground and scorning the wind’ has been prompted by that.

– You’d agree the false chests worn by the models are quite shocking…

The models ranged from young women to grannies, and their chests from these huge knockers to some rather pendulous examples. I thought it might be interesting to have a ‘dance of the saggy boobs’ (laughs). Black and white photos of windswept women with feet firmly on the ground are going to look serious no matter what, so I wanted to change that. Intellectual humor is all very well, but I prefer something more immediate. I think the only monochrome photos I’ve ever laughed at would be Naito Masatoshi’s series of old women ‘Baba baku-hatsu!’ and Morimura Yasumasa’s ‘Marilyn at Komaba’. Both of which typify the destructive capabilities of clowning.

What it means to show at Venice

– How do you place your practice and works in art historical terms?

I doubt any good could come of an artist attempting to position themselves in art history. Better not to seek any particular position or affiliation. When I hear young Western artists speak of wanting to be part of art history, wanting to succeed in New York, for instance, as if these were perfectly ordinary aspirations, I’m invariably struck by the extent of their faith in the unidirectional nature of time, and in fine art. I guess there’s something about being in Europe or North America that strengthens that faith.

I think my experiences in 2006-2007 out on what you might call the frontier, about as remote from art as it gets, have been critical for me. One of these experiences was teaching at a university. There was a cohort of eminent professors in fields such as manga and anime, but if the aim is to produce expression that extends to the lower reaches of the media, then naturally one becomes distanced from the art of individuals. Even though it’s a weak industry here in Japan, there’s a powerful elitism surrounding fine art, which seems to be designed with the Western bourgeoisie in mind. I sensed for the first time the helplessness of fine art. That probably did me good, actually (laughs). That kind of environment helps to clarify what one is personally engaged in – forcing you to question the nature of art, and the individuality of art practice, among other things. You have to be constantly questioning yourself, or that clarity dissipates.

My other experience on the fringes so to speak was on a panel at one of the major dailies, advising on the paper’s content. I went to the paper’s head office, where I found, in an overwhelmingly masculine environment, a strict hierarchy of politics, business, and society stories. Lifestyle and cultural matters were not deemed worthy of discussion by the panel, due to the lack of urgency in their coverage, while the arts seemed to be bundled together as a sort of metarealm, airy-fairy and somehow not a ‘real’ business sector. Of course, the only arts stories that ever make it onto the table are those that jump on the business bandwagon in a flashy way.

As I mentioned earlier, at a time when the line between entertainment, as typified by Hollywood, and art, becomes increasingly blurred, these experiences forced me to think about art and its ongoing proliferation. I believe it was a fruitful couple of years, in which I seriously considered that perhaps art is no more than an illusion, that perhaps it does not actually exist at all.

– You are a non-Western artist, but you don’t trade on that.

I find something duplicitous about only turning one’s own country, just the history of the country in which one was born, into art. This means of course that even if someone was carrying the burden of such history deep within their being, I’d wonder if it were really true. Nor do I like works that are cheap reflections of the forms of one’s own cultural sphere, or political issues. Appropriating that sort of thing wholesale will never change the world. For example, showing the ‘fiction’ of the nation state in a ‘fictional’ manner will ultimately leave you out of contention in any relevant discussion.

The miracles wrought by visuals do not, in my view, lie in this. Ideally, the very personal would be miraculously and inevitably linked to the public.

– Having said that, what are your own thoughts on the Venice Biennale?

The theatrical nature of the Venetian townscape endows it with a magic that puts everyone in the mood of wealthy aristocrats on a pleasure trip, and that festive atmosphere is very seductive. There’s an illusion that the town itself has chosen you, called you. For better or for worse, I’m no longer infatuated with Venice in that way, so I’ll be concentrating solely on doing my best, applying myself heart and soul to producing a good new piece. The work is all new and I produced the invitations, posters and catalogue myself. It’s like being a novice all over again at my first solo show at a rental gallery.

The city itself is an historical artifact, and once you’re part of the Biennale, which is like the shrine of Western art festivals, myriad conflicts arise as a result of being in the ring with Western art, feminism and such. There will be artists who as women of non-Western origin – thus a minority in two ways – will deploy every means at their disposal to achieve recognition. Whether my work is well-received or not, I look forward to some unexpected challenges.

Yanagi Miwa

Born in Kobe; lives in Kyoto. MFA from Kyoto City University of Arts. Held her first solo show in Kyoto in 1993, after which her Elevator Girl series received critical acclaim. Other series include My Grandmothers, Granddaughters, and Fairy Tale. She has been exhibiting internationally since 1997 when she participated in Prospect ’96 at Schirn Kunsthalle Frankfurt. She has had solo shows at the Deutsche Guggenheim (2004, Berlin), Marugame Genichiro-Inokuma Museum of Contemporary Art (2004), Hara Museum of Contemporary Art (2005, Tokyo), Ohara Museum of Art (2005, Kurashiki), Chelsea Art Museum (2007, New York), Museum of Fine Arts, Houston (2008), and Tokyo Metropolitan Museum of Photography (2009) among many others. Her forthcoming solo show po-po niangniang! at the National Museum of Art, Osaka (6.20-9.23) will feature her entire My Grandmothers series along with new works being shown at the Venice Biennale.

53rd Venice Biennale Making Worlds

6.7-11.22

Artistic director: Daniel Birnbaum

http://www.labiennale.org/it/Home.html

Yanagi Miwa’s Windswept Women: The Old Girls’ Troupe

is at the Japanese pavilion in the Giardini.