General director, Echigo-Tsumari Art Triennial 2009

For me, more important than the art is the festival. It is a festival of the land.

The Echigo-Tsumari Art Triennial, one of whose aims is to help revitalize the Echigo-Tsumari region, is held over a vast area of 760 square kilometers. We talked to the General Director, who, after much ‘trial and tribulation’, has developed the triennial into one of the world’s largest international arts festivals, about the past, present, and future of the festival.

Interview: ART iT

– This is the fourth Echigo-Tsumari Art Triennial. Looking back on the first one in 2000, how do you feel about it now?

It’s as though more than ten years have passed in no time at all as we’ve rushed around in a panic. Because, all things considered, organizing the first one was an extremely arduous process. We came up with the idea in 1996 and planned to hold the first festival in 1999, but we missed that target and it wasn’t until June 15, 2000 that we received authorization at a regional administration meeting, with the first triennial getting underway around a month later. So at that time, everyday we were busy just thinking about how to turn the idea for the festival into reality. Actually, even now it feels as though things haven’t changed that much.

– With so much time having passed since those initial ‘trials and tribulations’, you must enjoy the support of most of the locals by now, mustn’t you?

Around a third of the people in the villages that are actually involved are right behind the idea, but there are still sections of the population that aren’t interested at all. So we’ve still got some work to do. I think it comes down to a question of whether or not an arts festival including the entire local population can form the nucleus of a regional plan.

– This time, in commenting on holding the festival, you’ve used the phrase, “In hosting the fourth triennial, we’re entering a new phase.”

Oh, there I was referring entirely to the fact that we need a vehicle for regional self-reliance. Restructuring in this region came to an end ten or more years ago. Everyone is in a state of resignation, and they’re starting to think that they can get by as long as they’re getting money and as long as there is road construction. This is the same for everyone not only in Tsumari, but everywhere in Japan where restructuring has been fully implemented. So we need to create a real vision to turn this around.

To put it simply, this time around there are 11 abandoned schools. Of these, we’ve become involved in about four that have real prospects for the future. As for the remaining seven, although we’re able to use them as venues this year, we’ve been unable to bring them to the stage where they’re economically viable, so this is one of the issues that remains unresolved.

Another thing is what could be described as a kind of ‘real estate art’. Government money can’t be spent on empty houses. Because if this were the case, there’d be no end of people asking for their houses to be bought. So people are doing it themselves. For example, last time someone bought the Shedding House. This time we have to find buyers for Antony Gormley and Claude Leveque, for example. Unless we do this, these empty-house projects won’t be sustainable.

Claude Lévêque In silence or in noises © Claude Lévêque ADAGP 2009(Drawing 2009)

Claude Lévêque In silence or in noises © Claude Lévêque ADAGP 2009(Drawing 2009)

– With regard to money, it sounds as if you’ve always struggled.

As far as the budget goes, a budget of 900 million yen has been prepared for three years. Of that, Tokamachi and Tsunan contribute 100 million yen, while 550 million yen comes from sponsorship and passport sales. In other words, the executive committee is responsible for just 650 million yen, with NPOs having to take responsibility for the remaining 250 million yen. The limits of the role of government have become quite clear. Of the total budget of 900 million yen, governments are providing just 100 million yen. This is an extremely small proportion compared to similar projects around the world.

– Last time one of the themes of the festival was ‘land’. What about this time?

There’s no particular theme.

– The first triennial attracted attention due to the presence of a large number of eminent contemporary artists, and since then it’s expanded to include architecture, music, performance, and pottery in the form of Tsumari ware. Does this represent a change of policy of sorts?

No, that wasn’t the original intention. My definition of contemporary art is different from everyone else’s in one respect. I simply think there’s been a real problem with Japanese art since the Meiji period. When the Iwakura Mission went to Europe, they came back with the impression that culture was the concern of the state. That in itself is fine. But after that what did the people in charge of the country do? They created a system of art academies, built museums, and established the Tokyo School of Fine Arts. In other words, they were only interested in the kinds of things that could be displayed, managed, or taught using a manual. They interpreted fine art as meaning Western-style painting and sculpture only, and forgot about everything that’s basically the most interesting part for us, which is the festivals and the food and the gardens and the living rooms. I think that’s a huge problem.

– So why weren’t those things included at the outset?

Perhaps they simply couldn’t afford it, or the awareness was simply lacking. But there was another problem in that for the first triennial the only spaces we were allowed to use were public spaces. We couldn’t enter villages and of course houses were out of bounds. Only two villages put their hands up, and although we were able to use ten villages in the end after pleading our case, in most cases we were limited to places like parks and roads. For the second triennial 50 villages put up their hands immediately, and for the third we were able to use a lot of houses. There was no opposition to the Kohebi-tai (groups of mostly student festival volunteers) themselves moving around, so perhaps their activities made all the difference. Incidentally, there was an understanding that for work in public spaces, the source of the money would also be public. Some of the most impressive pieces at the first triennial were staged using money assigned to things like parks and roading projects. On the other hand it was difficult to do things in rice fields or private houses. The Kabakovs were an exception.

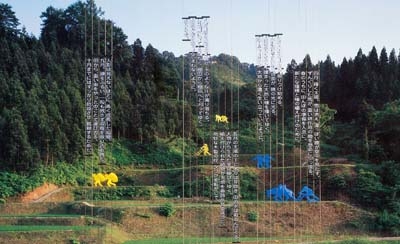

Ilya & Emilia Kabakov The Rice Field 2000 photo:ANZAΪ

Ilya & Emilia Kabakov The Rice Field 2000 photo:ANZAΪ

Kitagawa Fram: Part 2

https://www.art-it.asia/en/u/admin_interviews_e/TcQwSJKyouAFlOng4MUL/

Kitagawa Fram

Director of Art Front Gallery. Born 1946 in Takada (now Joetsu), Niigata. Graduated from Tokyo National University of Fine Arts and Music. Has initiated and organized exhibitions and events throughout Japan, including Antonio Gaudi in 1978 and the Apartheid Non! International Art Festival , which traveled to 194 locations. His activities range from exhibition production and public art direction for cities, architecture and town building to art and cultural criticism. Among his major public art projects is Faret Tachikawa (winner of the 1994 City Planning Institute of Japan award). He has been General Coordinator for Echigo-Tsumari Art Necklace Project since 1997 and General Coordinator for Echigo-Tsumari Art Triennial since 2000. He became director of the Niigata City Art Museum in 2007. Producer of Aqua Metropolis Osaka 2009 and General Director for the Setouchi International Art Festival 2010.

ART iT Picks: Echigo-Tsumari Art Triennial 2009

https://www.art-it.asia/en/u/admin_exrec_e/hPDFm8ObUjML5K61WNnG/