For me, more important than the art is the festival. It is a festival of the land.

The Echigo-Tsumari Art Triennial, one of whose aims is to help revitalize the Echigo-Tsumari region, is held over a vast area of 760 square kilometers. We talked to the General Director, who, after much ‘trial and tribulation’, has developed the triennial into one of the world’s largest international arts festivals, about the past, present, and future of the festival.

Part 1

https://www.art-it.asia/en/u/admin_interviews_e/bJWDOTLB9x7fniEZpPKG/

– In the late-1980s you organized the Apartheid Non! International Art Festival, which traveled to close to 200 places all over Japan. Did your experience of traveling around the regions on that occasion lead to the Echigo-Tsumari Art Triennial?

Before Apartheid Non! – in the late-1970s – I organized a Gaudi exhibition. So that came first. I approached Gaudi from a kind of regionalist perspective, and learnt that he was deeply concerned with the region in which he lived, including being a member of the Centre Excursionista de Catalunya (Catalan Touring Club), being arrested for speaking Catalan, and working on various projects with local craftspeople, for example. In the case of Apartheid Non! I wanted to create the exhibition in such a way that the audience could approach it from various different angles. In Japan, art is extremely categorized, with dedicated followers of contemporary art – and here I’m talking about the equivalent of NHK Symphony Orchestra subscribers, or in other words the kind of people who read Bijutsu Techo – numbering in the mere thousands. So in a sense I’ve done what I have because I felt compelled to do something about this situation.

– Some people have said that your approach shows the influence of people like your father, who was an expert on Ryokan, and Miyazawa Kenji. Is this something you yourself are conscious of?

There’s probably some truth in that. For me, the story of Miyazawa’s Rasuchijin Association is really important. He went about investigating various local things and enjoying all kinds of things together with his students. In a sense he was similar to Gaudi. But in the end I learnt the most from Gaudi. Working with craftspeople to create a 1:200 model without drawing up any plans, and then discussing one proposal after another before coming up with a 1:20 model. The idea being that this would continue until a 1:1 model was built, which would be the actual building. A part of me felt it would be really interesting to work with somebody like this, and in the process open up more opportunities for participation on the part of the audience. In other words, a part of it is that I thought it’s interesting not just to look but to get involved in the creating, which is the biggest difference I suppose. So in the case of the Echigo-Tsumari Art Triennial, while of course the artists are also involved, a big part of it is finding ways for the local people, members of the Kohebi-tai, and others to get involved.

– In other words, what you’re saying is that, while of course the art is at the core, your main goal is a kind of ‘restoration of community’?

‘Community’ is a word I don’t really like, or don’t really want to think about. I prefer the word ‘collaboration’. It’s something I do quite intentionally. For example, today we had another meeting, and what we talked about wasn’t really the kinds of works we want to see but problems concerning on-site logistics. In other words, I’m more interesting in things like how the Kohebi-tai will meet up, how they’ll get around, and what they’ll eat, and also regard these as far more important.

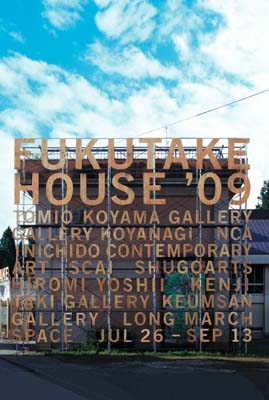

– At the last triennial a project called Fukutake House was launched. Seven commercial galleries responded to an invitation from Benesse Corporation’s Fukutake Soichiro (now General Producer of the Echigo-Tsumari Art Triennial) and held exhibits in an abandoned school. That surprised me.

It surprised me, too (laughs).

Fukutake House 2009 photo:Keizo Kioku

– That was Fukutake-san’s idea, wasn’t it?

Yes, that’s right. I’ve since become enlightened, and this time I’m putting a lot of energy into it. By that I mean – and this is something I didn’t really understand at first – that one of the main reasons Fukutake-san is doing it is because he wants to turn it into something that can be realized at a universal level.

– You mean not just at Echigo-Tsumari?

So that Fukutake-san doesn’t have to put so much energy into Echigo-Tsumari.

– Meaning?

In terms of things like the naming rights and getting the understanding of the locals. I didn’t really appreciate it at first, but Fukutake-san’s put a lot of effort into putting in place the structure.

Another thing is that without sponsorship of various kinds a lot of things probably wouldn’t become a reality. I was thinking solely of Echigo, but Fukutake-san thought we should think about the Asian market. There are various thoughts evolving inside his head, but this is one I came to understand a little bit and so this time I’m trying to do a kind of North-East Asia Art Village thing. So, for example, we sought sponsorship from the Haitai Foundation. This time, there’ll probably be several hundred people coming from Korea on various tours and suchlike.

– So you have in mind something like the Heyri Art Village in Korea?

Well, not quite on that scale, but some people from Heyri are coming over as part of a tour this time.

– I’d like to return to the topic of Fukutake House. What position do you see that kind of model of several commercial galleries coming together to create a single space having within the Echigo-Tsumari Art Triennial?

I think it’s great that various groups are helping out in this way. Another development I think is good is that people who move in different circles from me are doing all kinds of different things this time, such as Sugita Atsushi holding symposiums with critics and curators invited from Japan and overseas, and AIT doing a kind of school.

In a sense, it’s the sort of thing I’d been thinking about since I was in my twenties, and the Japanese reformists had tried to bring more and more people around to this way of thinking by acting as enlighteners of a kind. But I was allergic to this. I thought maybe they were wrong to be trying to fight the good fight together, and that I should be looking for a way to work with people I personally didn’t like. Anyway, the reason I decided that art was the place for me – and this is important – is because out of all the different subjects and classes, art is the only one where it’s OK to be different from everyone else. In the others, it’s all about being the best, being the fastest, or being correct. Even in PE points are awarded depending on how fast you are or how well you move. They’re all very similar in terms of their values. The only field in which you’re praised for being different is art. To put it a different way, art is the only subject based on the assumption that people are all different. In that sense, art suited me the best.

– So that’s why things that are different are welcomed at Echigo-Tsumari?

All things considered, I think it’s better to have some diversity. Without such an awareness, we wouldn’t have had pottery, and we wouldn’t have had ikebana. I work on the basis that anything goes. Fukutake-san is a better spokesperson than me when it comes to this. “I’m on the right and you’re on the left,” he says. I’m not on the left, but Fukutake-san says it’s good to have such different people working together. According to his way of thinking, it doesn’t matter whether you approach Mount Fuji from the right or the left.

– I see. Well, do you have a final message for our readers?

I’d love to see all kinds of people, including family groups, come to the festival. After all, art isn’t a question of good or bad, and it’s fun just to walk among the rice fields looking at the work. Also, Tsumari is at its best in summer. It’s so much more enjoyable to visit during an event when there are lots of people around.

– So what you’re saying is that the important thing about the Echigo-Tsumari Art Triennial isn’t so much the art but the festival?

For me, the festival is the most important thing. It is a festival of the land.

Kitagawa Fram

Director of Art Front Gallery. Born 1946 in Takada (now Joetsu), Niigata. Graduated from Tokyo National University of Fine Arts and Music. Has initiated and organized exhibitions and events throughout Japan, including Antonio Gaudi in 1978 and the Apartheid Non! International Art Festival , which traveled to 194 locations. His activities range from exhibition production and public art direction for cities, architecture and town building to art and cultural criticism. Among his major public art projects is Faret Tachikawa (winner of the 1994 City Planning Institute of Japan award). He has been General Coordinator for Echigo-Tsumari Art Necklace Project since 1997 and General Coordinator for Echigo-Tsumari Art Triennial since 2000. He became director of the Niigata City Art Museum in 2007. Producer of Aqua Metropolis Osaka 2009 and General Director for the Setouchi International Art Festival 2010.

Echigo-Tsumari Art Triennial 2009

7.26–9.13

Echigo-Tsumari region (Tokamachi City and Tsunan Town, Niigata Prefecture)

http://www.echigo-tsumari.jp/

ART iT Feature: Echigo-Tsumari Art Triennial 2009

https://www.art-it.asia/en/u/admin_feature_e/YoazcUFpqvKVPjsdLRbm/