Models of Agency

By Andrew Maerkle

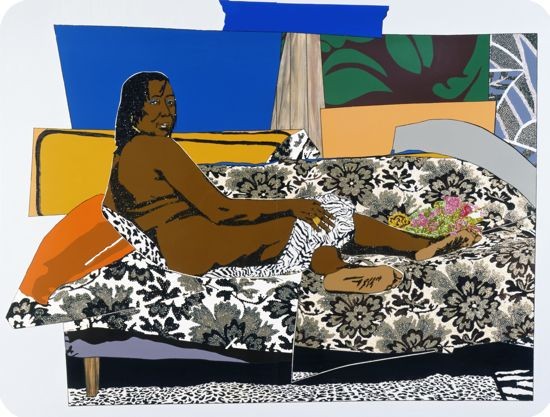

Mama Bush: One of a Kind Two (2009), acrylic, rhinestone and enamel on wood panel, approx 274 x 366 cm. All images: Unless otherwise noted, courtesy Mickalene Thomas Studio.

Mama Bush: One of a Kind Two (2009), acrylic, rhinestone and enamel on wood panel, approx 274 x 366 cm. All images: Unless otherwise noted, courtesy Mickalene Thomas Studio.Interview:

ART iT: Your work engages with images of black women in settings that evoke both the aesthetic of 1970s Blaxploitation cinema and the composition of historical European paintings. In this day and age, does working with images of blackness necessarily mean that you are dealing with black identity?

MT: When I’m making the work, I don’t necessarily think of it as being representative of a specific cultural or ethnic identity. That may be one of the inspirations, but it’s really more an extension of who I am. For African-American artists, any time you make work that in any way deals with your identity there’s a tendency for people to want to think of it only within that framework. But I personally think there are universal elements to the work. I would like to think it speaks to the human spirit and there’s a relationship that anyone can find familiar. To me, that comes back to thinking about painting and art history more than contemporary concepts of cultural identity.

I approach the work primarily through the formal aspects of making a painting, and the end product is about painting. But I want to use the black body because the idea of placing it in a context where it is not usually seen or spoken about enables comparisons to the Western ideology of beauty. From my experience, in Western art history when you see images of black women they’re generally depicted in positions of servitude or looked at through an anthropological perspective. They are not seen in Western art history in the archetypal explorations of notions of beauty. I was always interested in those images that are considered beautiful and related to the self. I was interested in whether I could change those perspectives with the art that I made, if I could play with how people might look, not only on a stereotypical level but also maybe erase that and challenge viewers in their own perceptions of images. I think that’s why I always go back to using formulas from Western art as a mechanism for making the paintings. That way, when I insert the black body, it has a relationship with something that was already there and exists.

ART iT: Are you familiar with the work of the Japanese media artist Yasumasa Morimura, whose “Daughter of Art History” series of photographs also reworked the Western art canon? I think there are some overlaps between what the two of you do, although clearly different results.

MT: I’m familiar with the work, although I’ve never looked at it in depth. I know that Manet was influenced by Japanese woodblock prints, evident in his use of color, the play with pictorial space and the way he constructed landscapes. I’m very conscientious of that. When I look at people I don’t only stop there but also look at their references.

The similarities with Morimura are not something I’ve particularly thought about, though, when I look at his work. I think it’s an interesting comparison and it makes me want to look at it more. But just as Matisse looked at Manet, you have all these artists that come out of one another and use each other as a way of finding out how to make something new.

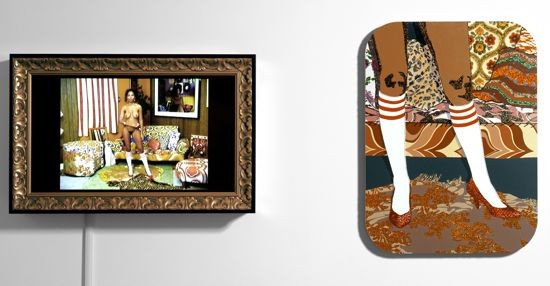

Both: Oh Mickey (2008), DVD and framed monitor, rhinestones, acrylic and enamel on wood panel, diptych, approx 81 x 127 x 14 cm (framed monitor) and 122 x 91 x 5 cm (painting).

Both: Oh Mickey (2008), DVD and framed monitor, rhinestones, acrylic and enamel on wood panel, diptych, approx 81 x 127 x 14 cm (framed monitor) and 122 x 91 x 5 cm (painting).ART iT: For me the interesting thing about yourself and Morimura is that it’s not just this idea of inserting a foreign body into the Western art canon but also the process of making elaborate sets, photographing them and then working from the photograph, where each image becomes a performance or a documentation of a performance.

MT: I see his work as being more performative than my own. Certainly, there is an element of performance in my work because I want to create my own space, see it directly, and be a part of that space. I become a kind of art director when I’m working with the models, and I also work with a stylist, a makeup artist and a lighting designer. It’s a collaborative production, and the models themselves bring something that I can’t necessarily bring to the work, which is really exciting.

I’m interested in performance in the sense that I can expand on the idea of the space and how I work with the models. I think there’s something there that I can pursue further. That’s why I started the “Ain’t I a Woman” series of videos recording the models as I photographed them. I felt there was something lost in the photo stills and in the paintings that could be captured on video. For me the performative element develops from wanting viewers to see all sides of what happens.

ART iT: The videos capture those shifts between confidence and vulnerability that the models experience during the shoot, whereas the photo captures only one moment.

MT: Yes, there are moments when the models find within themselves a decisiveness of action, and that can be generated by both the vulnerability and the confidence of knowing which is the right angle they want to portray. Those subtleties are the moments that you want to capture with photography but can’t always capture.

I actually used to do more performance when I was in graduate school at Yale, where I would dress up as this alter ego that I named “Quanikah.” Growing up in New Jersey in the late 1970s there was always this need – perhaps inspired by the Black Panther movement and even Marcus Garvey’s Back to Africa movement – to reclaim yourself by having an “African” name. My cousins and family members all changed their names to “African” names that we made up for ourselves, choosing things that sounded different and rooted in Afrocentric thought. When I go home, some of my cousins still call me Quanikah.

But who is Quanikah? She grew up in South Jersey in Camden and is now attending Yale – I made her into this true person. Thinking about how she might look, was she a local from the New Haven community? There was a divide between the town and the university; most of the African-Americans at Yale worked there, so those of us who were students were always asked to show our IDs or otherwise prove we belonged.

I decided to do this project with Quanikah going to Yale, dressed as a local, for a performance. I was stopped much more frequently than I had been up to that point, and many of my peers in the art school didn’t recognize me because I was made up in a sort of costume, wearing a wig and earrings and fake nails. It was quite an experience. I was considering Cindy Sherman at the time and those moments of transformation when you are perceived as someone else, how people respond to you based on what you look like or what you’re wearing, as opposed to who you are, and the story that can be woven around that experience. That story took the form of a series of photographs that I produced while at Yale.

Left: Negress (2001/05), C-print, approx 122 x 109 cm. Right: Negress 4 (2001/05), C-print, dimensions not available.

ART iT: I read that you started out making abstract works at university. Why did you feel that abstraction wasn’t working for you at that time, or why did you feel it was necessary to push further into figuration and portraiture?

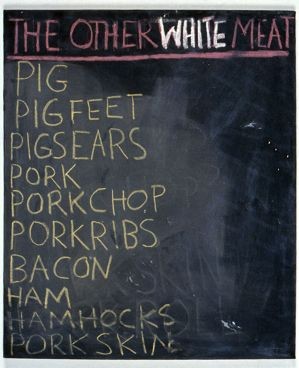

MT: When I was doing my undergraduate degree at Pratt I always felt that I wasn’t good with the figure, and I always avoided figure painting courses. I responded more to painters like Bryce Marden, Terry Winters and Agnes Martin. But once I got to Yale I was challenged about why I was doing abstract work and what it really meant to me. I didn’t know how to justify it except through talking about my works as paintings. I started experimenting with text paintings, removing anything that had to do with color, form or representation. I thought maybe I could work with text and still work abstractly.

Eventually, I felt it was necessary to work with the figure. So while I was at Yale there were two bodies of work I was making in my studio, some were representational and some were abstract, and I was looking for a way to bring the two together. It’s slowly getting there. I still think there’s a divide even though there are abstract elements in the current work if you remove the figure. That’s what keeps me making the work. For me, there’s so much more room and conceptual play with abstraction. I like contending with that understanding of what’s abstract, what’s expressionism, what’s conceptual theory?

I started responding to how people use the figure in different ways. I remember seeing Gary Hume and being impressed by how he uses the figure abstractly whereby it’s really about forms and color, or how Kara Walker uses the figure. Her drawing is impeccable, and I think that’s why she’s able to do these cutout silhouettes with perspectival space, because she understands drawing. She’s a conceptual draftsman more than anything else. For me abstraction is that thing: I know how to use abstraction; I’m rooted in it and understand it.

The figures came more from the critical discussion around my work during graduate school: Why are you, as a young black woman, dealing with these ideas? How are you going to bring them together? It’s not that they expected me to work with black issues, it’s more that they were curious as to why I, personally, was so invested in the language of abstraction. That’s why I’m interested in bringing these two languages together.

Top: Black Cock, Black Bitch (2000). Bottom left: Untitled (2000). Bottom right: Untitled (2000).

ART iT: Was the Quanikah experiment what shifted you into figuration?

MT: Yes, that and photographing myself and my mother. I had started using symbols and signifiers in my paintings related to black male masculinity and black female sexuality, pairing graphic images together. For example, I made a glitter painting of a rooster and a female pit-bull, which I put together as the “black cock” and “black bitch” in a play with visual semantics. I was working with images and slang and wordplay, and that became a conceptual way of using abstraction and words. I was looking at Mel Bochner a lot then, and Glenn Ligon was a big influence as well in trying to understand how to make these images without being heavy-handed or forcing the ideas. And then it took new shape and specificity when I brought photography into it.

ART iT: You mention your interest in the history of abstraction. I hadn’t realized how big your recent works are until I saw them in person. How do you end up working at such a big scale, is it necessarily a response to the idea of the macho painter or is it more driven by the demands of the material?

MT: I think it’s a little of both. There’s definitely the bravado of knowing you can pull off a big painting. And it is a boy thing. I like wrestling with those male notions of, “They’ve done it, why can’t I do it too? How will I do it?”

Initially, I worked on a small scale but I found it limiting in terms of composition. I started thinking about pictorial space and how to change the flat, graphic space of my work into a more complicated three-dimensional space – how to play with flat planes and perspective. There’s always this desire to make the painter’s painting, to have this Clement Greenberg notion of the painted surface and its relationship with the viewer. I feel the scale is important because it determines how the paintings are viewed and what they mean. I enjoy the challenge of working large because I have to contend with the relationships, there’s a struggle of trying to understand all the components and make them work in a painting.

Usually, when I work on a small scale I get it so quickly that it doesn’t allow time for exploring. After a while, working at a certain size you know what’s going to happen before you do it, and I felt I knew my system too well and had to reinvent it. I think the challenge was for my self. There are certainly some works that are better on a small-scale, like the multi-panel portraits, and I think those work well because they are graphic images that are contained in their space and the point is there.

But I love struggling with the painting when I’m in the studio and I can’t get it and have to leave it and come back to it four or five times. I’ve learned just by looking at, say, Jasper Johns and certain images that resonate with me, that whatever that feeling is when you’re in front of those paintings is what I want people to feel in front of my own paintings.

Installation view of “Mickalene Thomas – One of a Kind Two” at the Hara

Installation view of “Mickalene Thomas – One of a Kind Two” at the Hara Museum of Contemporary Art, Tokyo, 2011. Photo Keizo Kioku, courtesy

the artist and Hara Museum of Contemporary Art.

Work by Mickalene Thomas will be on display in a solo exhibition at Lehmann Maupin Gallery, New York, from September 15 to October 29, and is currently included in the group shows “EAT ME,” at Goodman Gallery in Cape Town through September 4, and “Africolor,” at Danziger Projects in New York through September 10. Commissioned by the Museum of Modern Art, New York, Thomas’ Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe: Les Trois Femmes Nois is currently on view at the Modern Restaurant.