THE MANIFEST DESTINY OF BORROWED SCENERY

By Andrew Maerkle

Installation view of “Sam Durant: Borrowed Scenery” at Blum & Poe, Tokyo, 2015, with 1905, Japan Defeats Russia, Empire (2015) in foreground, graphite and colored pencil on paper, two components, 46 x 59.7 cm and 24.7 x 31.7 cm in frame, respectively. Photo Keizo Kioku. All images: Unless otherwise noted © Sam Durant, courtesy the artist and Blum & Poe, Los Angeles/New York/Tokyo.

Installation view of “Sam Durant: Borrowed Scenery” at Blum & Poe, Tokyo, 2015, with 1905, Japan Defeats Russia, Empire (2015) in foreground, graphite and colored pencil on paper, two components, 46 x 59.7 cm and 24.7 x 31.7 cm in frame, respectively. Photo Keizo Kioku. All images: Unless otherwise noted © Sam Durant, courtesy the artist and Blum & Poe, Los Angeles/New York/Tokyo.

Born in Seattle in 1961, Sam Durant was raised near Boston and is now based in Los Angeles, where he teaches at the California Institute of the Arts. Deftly shifting across diverse media, Durant is known for works that engage with the underside of official US history and the deep-rooted power imbalances that structure contemporary US society. His projects often develop out of archival research, and employ drawing as an initial technique for transferring images and materials from the archive “back” into the present. This strategy of transposition or displacement takes on expanded form in works such as Proposal for White and Indian Dead Monument Transpositions, Washington, DC (2005), for which Durant proposed gathering monuments to victims of conflicts between white settlers and Native Americans from across the country and moving them to the National Mall in Washington, DC – visualized, in part, by an installation of reconstructed monuments. For another project, entitled “Scenes from the Pilgrim Story: Myths, Massacres and Monuments” (2006-07), he acquired the didactic dioramas from the now defunct Plymouth National Wax Museum in Plymouth, Massachusetts, and used them as the basis for a series of installations and photographs investigating the inherent biases in historical narratives. He has also made participatory projects such as Labyrinth (2015), a public work installed in front of Philadelphia’s City Hall that was realized in consultation with the inmates of a nearby state prison.

While he has received much critical acclaim for these works, Durant was the subject of controversy earlier this year when his large-scale installation Scaffold (2012) was erected in the Walker Art Center’s Minneapolis Sculpture Garden. The work was a chimerical representation of scaffolds used for public executions from across US history, including those used for the abolitionist John Brown (1859); the anarchists accused of instigating the Haymarket Riot in Chicago (1887); and Rainey Bethea, the last person to be publicly executed in the US (1936). The most prominent among these was the Mankato gallows, used in 1862 to execute 38 Dakota Indians who were accused of murdering white settlers during the Dakota War of the same year. Members of the present-day Dakota community in the Minneapolis area were upset at seeing this reminder of their traumatic past on such prominent public display, and after a process of dialogue and concilliation, Durant and the Walker Art Center agreed to remove the work and hand it over to the Dakota elders for disposal.

ART iT recently had the chance to speak with Durant about his practice and how it relates to issues of cultural appropriation when he came to Japan for the opening of the Yokohama Triennale 2017: “Islands, Constellations & Galapagos,” where he is displaying a group of works inspired by the encounter between US and Japanese officials during Commodore Matthew Perry’s expedition to “open” Japanese ports to international trade. What follows is an edited and condensed version of the original interview.

The Yokohama Triennale 2017: “Islands, Constellations & Galapagos” remains on view at multiple venues in Yokohama through November 5.

I.

Proposal for White and Indian Dead Monument Transpositions, Washington, D.C. (2005), MDF, fiberglass, foam, enamel, acrylic, basswood, balsa wood, birch veneer and copper, 30 monuments, installed dimensions variable, installation view at Paula Cooper Gallery, New York, 2005. © Sam Durant, courtesy the artist and Paula Cooper Gallery, New York.

Proposal for White and Indian Dead Monument Transpositions, Washington, D.C. (2005), MDF, fiberglass, foam, enamel, acrylic, basswood, balsa wood, birch veneer and copper, 30 monuments, installed dimensions variable, installation view at Paula Cooper Gallery, New York, 2005. © Sam Durant, courtesy the artist and Paula Cooper Gallery, New York.ART iT: You’ve mined US history for subject matter throughout your career, making work on issues such as the Native American genocide and capital punishment, and collaborating with figures like Emory Douglas, the former minister of culture of the Black Panther Party. However, given the racial inequalities in US society, you necessarily approach these topics from a position of empowerment as a white male artist – and there are some people who might see that as a form of cultural appropriation or exploitation. How do you understand your relationship to the material you work with, and has your understanding changed over the course of your career?

SD: You mention work I’ve done on the history of race and race relations in the US and how it plays out in terms of political power, or systems of inequality and oppression. Although I’m a white male, I believe that US history is “our” history, and it’s important for the white community, if there is such a thing, to work through these issues. It’s our problem just as much as it is for African Americans, Native Americans or any minority group – and maybe more so, because white supremacy is still in effect.

Lately, there has been a reemergence of a very polarizing kind of identity politics where some people from minority communities are claiming that this history is theirs and only theirs, and that whites should not speak about it. There are good reasons for that position, but it’s something we have to be careful about, taking the specifics of each and every situation into account. We run into problems when we try to make blanket rules and either/or binaries. We need to engage in the nuance and fine grain of a particular situation and be ready to arrive at possibly surprising conclusions.

At the risk of contradicting myself, though, I would say that in general terms, history belongs to all of us and we have to remember and retell it not from the point of view of the winners but rather in a way that shows its effects on all of the participants. The so called “winners” have a responsibility to step back and look at the other side of history and learn about it. That’s what I’ve tried to do over the years.

ART iT: In an artist statement on the “Scenes from the Pilgrim Story: Myths, Massacres and Monuments” project, you said the work is addressed to “white, Euro-ethnic Americans.” Does that preclude the participation of non-white viewers?

SD: Yes, I’ve always said my work is primarily for that audience – that’s the art world as well as the broader mainstream population in the US. The art world is overwhelmingly white and Euro-ethnic, just like me. Of course my work is open to anyone, and I hope it’s accessible to anyone. Until very recently, it’s been my experience that work that I’ve done about the US government’s genocidal policies toward Native Americans has been supported, understood, talked about, and shown by Native Americans in a variety of ways. Native American curators have included my work in their shows and projects and written about it. I hope that they would continue to support me when they think I deserve that support, even if others in the community disagree. It’s the same with work I’ve done on issues around the civil rights movement and racial oppression in the US from slavery to the present day. It’s certainly open to African Americans. It’s made in consultation with them, trying to be respectful of identity – theirs, mine and the particular political community in question.

What I am talking about in my work is the idea that race is constituted as a political/ideological position in the US. I am not talking about individual people and their experiences – it’s up to those individuals to represent themselves, as I would never speak for someone else. What I am engaging with is not individuals or their subjectivities, but the “black community” as a political community that has been systematically oppressed from before day one in the US. It’s that system of oppression – institutional structural racism – that my work is about. Whites are the ones benefitting from it, including me, and we are also the ones who must work to dismantle it. I really like the new slogan coming out of the Black Lives Matter movement: “White silence equals violence.”

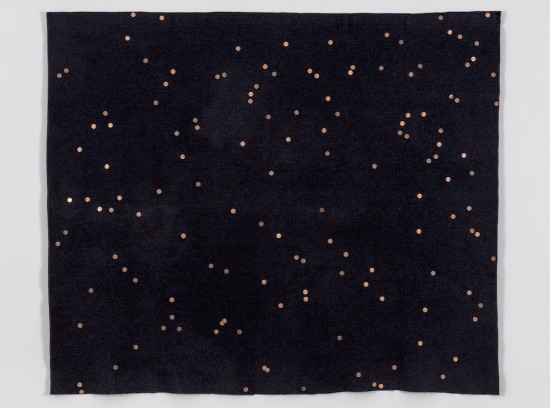

Above: Dream Map, Polaris (2016), military blanket, Lincoln pennies, epoxy, 160 x 188 cm. Below: Some Information on Boston School Desegregation (2004), mixed media installation with furniture, books, two-channel video, sound, wall text, included in “Through the Gates: Brown vs. the Board of Education,” California African American Museum, Los Angeles, 2004.

Above: Dream Map, Polaris (2016), military blanket, Lincoln pennies, epoxy, 160 x 188 cm. Below: Some Information on Boston School Desegregation (2004), mixed media installation with furniture, books, two-channel video, sound, wall text, included in “Through the Gates: Brown vs. the Board of Education,” California African American Museum, Los Angeles, 2004.ART iT: Do you consider your own work to be political as such?

SD: I think all artwork is political, but the art world doesn’t really agree with that. For most people, only the kind of art that makes its politics explicit is political. That’s just the way it is at the moment, although perhaps at some point in the future the label “political art” will no longer even be necessary. In the meantime, I am proud of being labeled a political artist, and there needs to be more of us willing to accept that label. I have learned so much from feminism, from women who have struggled with all of the labels put on them and the inspiring artists who take on the label “feminist” proudly and openly. Their courage helps me to embrace a term that might otherwise seem minimizing.

ART iT: Instead of making explicit political statements, your works tend to operate through gestures of juxtaposition. I’m thinking of Proposal for White and Indian Dead Monument Transpositions, Washington, DC (2005), or even the works here in Yokohama comparing the different representations of the Americans and Japanese at the time of their encounter through the Perry Expedition.

SD: The political dimension is more of a subtext. The work here in Yokohama tries to bring in the issue of the artist and the way the artist functions in the politics of the real world or, say, imperialism. Commodore Perry brought an artist, Peter Wilhelm Heine, with him on the expedition. Heine made records of the mission to Japan and then published them in the US to tell the story of the expedition. In this case, it’s very obvious how an artist can both be part of history and also actually involved in creating the historical narrative. And we can see clearly that Heine told the story he was supposed to tell. What I did was to put Heine’s images in comparison with those by Japanese artists who depicted the same scenes, but from the Japanese perspective. I find it fascinating to see these two sides of the same story told by artists at a time that was more or less before photography. And implicating myself was part of the project as well. Artists are not so clean. We have this idea that a political artist should be righteous and ethical and moral. Maybe it’s not so clear cut – especially for someone coming from the US. How clean can I be clean, when I come from the most powerful and destructive empire in history? It’s uncomfortable to think about.

Installation view of “Sam Durant: Borrowed Scenery” at Blum & Poe, Tokyo, with Passing the Rubicon, Delivering the President’s Letter, at Leisure (2015), 1853-1900, Map of the World, Japan Centered (2015), and Borrowed Scenery (2015) visible from left to right. Photo Keizo Kioku.

Installation view of “Sam Durant: Borrowed Scenery” at Blum & Poe, Tokyo, with Passing the Rubicon, Delivering the President’s Letter, at Leisure (2015), 1853-1900, Map of the World, Japan Centered (2015), and Borrowed Scenery (2015) visible from left to right. Photo Keizo Kioku.ART iT: What drove you to work with these issues in the first place?

SD: I grew up in Massachusetts during the Vietnam War and in the wake of the civil rights movement. Boston was a very racist city. It was so segregated that in the 1970s the federal government had to intervene to force the school system to desegregate. Seeing how the day-to-day effects of racism were playing out with young people was a big part of my adolescence. At the time, all the cool people were political activists. I looked up to people who were going to anti-war demonstrations and going to the South to join the voting rights drives. That’s how I learned to see the world.

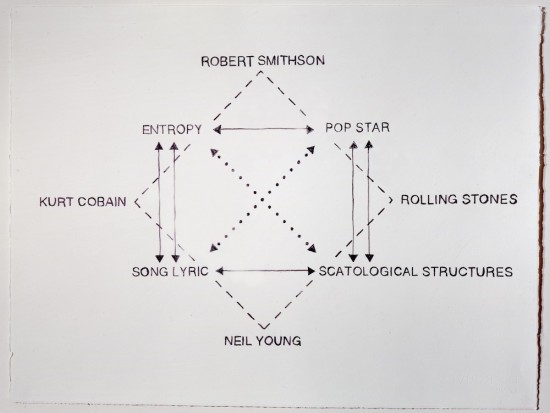

ART iT: You also made a number of works referencing Robert Smithson, who seems to have been a big influence on you. How does he fit into a concern with social inequality and racial oppression?

SD: Smithson was active during that period in the 1960s and early ’70s, but he died young in a plane crash. He was a tragic and mythic figure for me. The main concept he applied in his artwork was entropy. We could say that the reason we all die and everything dies is the law of entropy, and to me that also seemed to be connected with what happened in the social and political moment in the US after 1968. I saw it as an entropic collapse, not understanding that the right-wing counterrevolution was actively destroying the social movements. Looking back on the period in the mid-1990s when I was making that work, I think I was interested in looking at the archives from my childhood – the social, political and cultural forces that were at play in the world while I was unaware, still “at play” as a child.

ART iT: By entropic collapse, are you referring to the end of the civil rights movement and the start of neoliberalism?

SD: I probably spent two or three years making a whole series of drawings, sculptures and installations looking at the intersections between music and culture and Smithson’s work. I was thinking about the end of youth culture or hippie culture as a believable alternative to repressive reality, and also about the radical political movements. At the time I didn’t understand that the reason these things were dying out, so to speak, was because of the arrival of a whole new economic regime and the political forces to institute it: neoliberalism.

Above: Quaternary Field/Associative Diagram (1998), pencil on paper, 55.9 x 74.9 cm. Below: Abandoned House #4 (1995), foam core, cardboard, Plexiglas, tape, spray enamel, wood, and metal, 64.8 x 104.1 x 11.4 cm (not including stand).

Above: Quaternary Field/Associative Diagram (1998), pencil on paper, 55.9 x 74.9 cm. Below: Abandoned House #4 (1995), foam core, cardboard, Plexiglas, tape, spray enamel, wood, and metal, 64.8 x 104.1 x 11.4 cm (not including stand).ART iT: Certainly, the “Abandoned Houses” series of maquettes that you made in the early 1990s, which depict dilapidated modernist homes, seem to hint at the idea of a society that is falling apart.

SD: There’s something archetypal about the architectural model, the maquette, the miniature. We remember it from our childhood, it’s there in the psyche – in different ways probably for different people – and it’s fascinating how it gets your imagination going into fantasy production. For many years, I worked as a carpenter and house builder to support myself, and I had a very class-based relationship to architecture. There was always a degree of animosity toward architects among the builders. We thought, hey, we’re the workers and you’re the bosses and intellectuals who keep your hands clean and tell us what to build. It’s totally unfair, but that was one psychological aspect that informed the architectural models and other works, so I think in some sense it was my personal reckoning with architecture.

The models were based on the iconic houses built in the mid-20th century in Los Angeles, which weren’t really valued in the early 1990s the way they are now. It was right before midcentury modern started to gain a lot of traction in the mass media, and the houses were being “remodeled” as they were sold to new owners or passed to the next generation. Owners were putting on colonnaded porches or Spanish Revival additions, trying to make the houses look anything but modernist. I saw these “remodels” as forms of critique – some of it class based, some psychological – of the original designs, which were to some degree forms of social engineering. The architects were proposing a different way of living, and in the end many of the people who lived in those houses didn’t want to live that way. It was a metaphor for a lot of different things.

I | II

Sam Durant: The Manifest Destiny of Borrowed Scenery