COLD DARK DEEP AND ABSOLUTELY CLEAR

By Andrew Maerkle

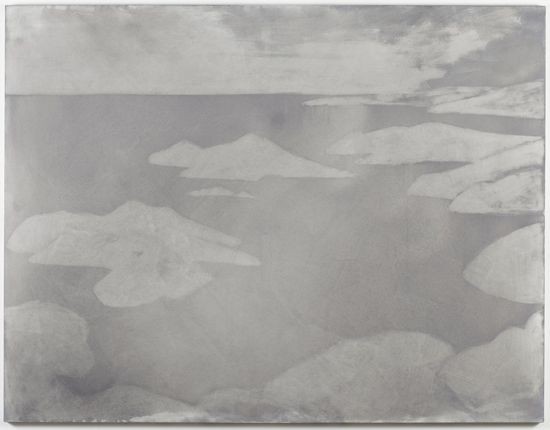

Saturday’s Ledge (Grey) (2014), watercolor on canvas, 101.5 x 132 cm. All images: Unless otherwise noted, © Silke Otto-Knapp, courtesy Taka Ishii Gallery, Tokyo.

Saturday’s Ledge (Grey) (2014), watercolor on canvas, 101.5 x 132 cm. All images: Unless otherwise noted, © Silke Otto-Knapp, courtesy Taka Ishii Gallery, Tokyo.Born in Germany in 1970, Silke Otto-Knapp is now based in Los Angeles after many years in London. She is known for paintings in watercolor and gouache on canvas that destabilize conventions of figuration and illusionistic space through mechanisms such as flattened or dramatically skewed perspective, as well as a unique approach to materiality, in the building up and removal of marks and washes, that evokes temporal processes of both accretion and effacement. Often incorporating monochrome or subdued palettes to depict motifs ranging from urban landscapes and garden scenes to dancers and showgirls, these works evoke a decontextualized reality in which certain details are heightened and others suppressed, as in a dream world or weathered photograph.

Otto-Knapp was recently in Japan for a two-person exhibition at Taka Ishii Gallery with the Austrian artist Florian Pumhösl, entitled “Ratio of distance.” Conceived as something of an exhibition in parallel, the show features Otto-Knapp’s paintings based on the landscape around Fogo Island, Newfoundland, to where she has returned periodically over recent years for residencies at the institution Fogo Island Arts, and Pumhösl’s abstractions on plaster panel derived from nautical maps. In this way, the two artist’s works illuminate each other without being confined to a specific theme. This latest exhibition concludes a year for Otto-Knapp that included the solo exhibitions “Monday or Tuesday” at the Camden Arts Centre in London and “Questions of Travel” at Fogo Island Arts and Kunsthalle Wien.

“Ratio of distance” opened on November 22 and continues through December 20. ART iT spoke with Otto-Knapp before the opening of the exhibition to learn more about her practice and the ideas informing her works.

Interview:

Installation view of the solo exhibition “Monday or Tuesday” at the Camden Arts Centre, London, 2014. Photo Marcus Leith, courtesy greengrassi, London.

Installation view of the solo exhibition “Monday or Tuesday” at the Camden Arts Centre, London, 2014. Photo Marcus Leith, courtesy greengrassi, London.ART iT: You’ve covered a wide range of motifs in your paintings, from dancers to cityscapes of places like Los Angeles and Las Vegas, and interior scenes based on historical photographs. The focus of this new series is on islands. Could you talk about this latest development?

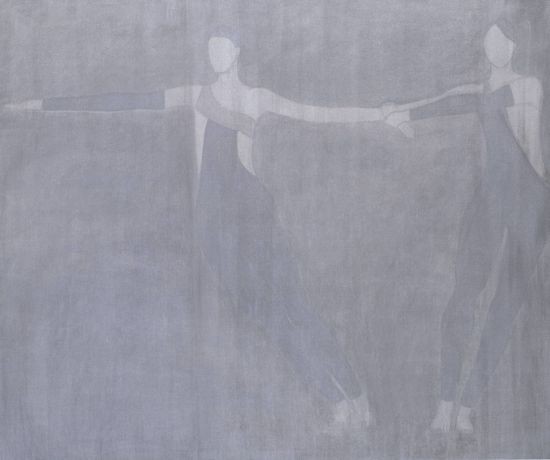

SOP: I wouldn’t describe it as a linear development. It seems to me that I keep coming back to the same ideas, which originate from thinking about painting and the pictorial space. The works here in Tokyo are based on photographs of the place I produced them in – a small island in the North Atlantic – but the resulting paintings don’t depict the actual place. They are are concerned with the pictorial space as a staged situation in a way similar to paintings that work with figures or elements of stage design. In older paintings I have used the motif of a dancer in such a way that the choreographic movement describes the pictorial space and becomes a kind of stage.

I became interested in landscape motifs through thinking about theatrical backdrops and the space of the proscenium stage. For me an empty canvas always comes with the somewhat overwhelming promise of illusion – the window to the world. I prefer to think about the pictorial space more like a proscenium stage because it suggests a limited, tightly framed space that is very clearly constructed. A proscenium always works with a frontal view, perhaps seen from above. It operates with a simple background and is able to construct a sense of depth by way of adding simple structural elements. Through very simple means a stage is able to conjure a complete world that is aware of its own artifice. Gradually, my attention shifted from looking at figures that are describing the space itself to backdrops and stage designs. My more recent paintings are trying to address the space and history of landscape painting from the perspective of a theatrical backdrop.

ART iT: From certain angles the paintings here look like they were done in relief, or evoke enamel printing plates, giving them a spatial quality. Could you talk about how you make the works?

SOP: The paintings are reduced in color and detail (such as line work); I try to concentrate on surface and space instead. The different island-shapes in the new paintings can, for instance, describe a positive space while the ocean and sky exist as the negative space; or it could be exactly the other way around. I am trying to establish a tension between foreground and background that shifts the motif into the pictorial space and transforms it.

I think that is reflected in the process of painting with watercolor, which is a process of removing as much as adding. I begin by making drawings of my chosen image, which help me to identify the motif and the right dimension and tone. At some point, I transfer the motif to the canvas, and then almost instantly begin to remove it with water so that it dissolves and leaves marks. This produces a kind of negative brushstroke constituted by the mark left after the pigment is removed. I like this imprint or trace of a physical process that appears without the buildup of an oil painting. The information that has been removed is as important as the information that emerges. It’s almost as if I have to find the motif again in the pictorial space through removing and adding washes of pigment and water.

ART iT: I’m curious how you think about time in your works. In the paintings with the dancing figures, time is implied in the movement of the body. An island, or an island landscape, is something that you move through and around – as opposed to a mountain, which is the end of the horizon – and in this sense I think there’s also an aspect of that kind of time through movement here in these works. Then there’s the historical time you work with in excavating the history of modernism and modern dance, so maybe these works are also a kind of geological excavation?

SOP: I think the painting process has a bit of that sense of excavation, because what you see is the product of a removal process. Or, rather, the picture is produced through a process of slow sedimentation. Certainly, there is the actual time of the dancers’ movements in the paintings. There is the time experienced by the viewer moving in the exhibition space in relationship to the paintings, where different motifs are recurring, or occurring in different ways. Then there is the historical time of evoking specific characters or moments in the history of dance, literature, or art history. I introduce this historical time pictorially, by using these motifs or referring to particular characters, but the painting process itself is manifest in how the material surface of the painting exists in the present time.

ART iT: Some of the historical figures who have inspired your works include the artist Florine Stettheimer and the choreographer Yvonne Rainer, as well as the Ballets Russes.

SOP: Yes. For this project it was important to me to approach the motif of the seascape without producing an illustration or a sentimental representation. I tried to think about this problem via the work of the American poet Elizabeth Bishop, a modernist writer who grew up in Nova Scotia, Canada, and later lived in Florida, then moved to Brazil and eventually returned to the US. A lot of her writing is about the idea of geography and travel, and the experience of living in different places, in a way that is descriptive and unsentimental. It’s as though the writer is looking at something and observing rather than interpreting it or expressing emotion. So I actually started by painting portraits of Elisabeth Bishop. I often imagine protagonists for my paintings who don’t directly appear – other examples are Virginia Woolf or Florine Stettheimer. I am also interested in figures such as the Russian artist Natalia Gontcharova, from whom I might pick up a particular motif or design for reworking, without referring to her work directly. I am in the process of working on a show for a museum in Canada, and we are planning to have one space that will bring together some of the characters who have been invoked in such “portraits.”

Both: Installation view of Silke Otto-Knapp & Florian Pumhösl, “Ratio of distance,” at Taka Ishii Gallery, Tokyo, 2014. Photo Kenji Takahashi.

Both: Installation view of Silke Otto-Knapp & Florian Pumhösl, “Ratio of distance,” at Taka Ishii Gallery, Tokyo, 2014. Photo Kenji Takahashi.ART iT: Where does the necessity of addressing history through painting come from for you?

SOP: I think my interest in painting is really the starting point. I think about setting specific parameters that enable me to make a painting. It’s like setting up a framework with limitations that I can act within. I also pay close attention to the exhibition situation and creating relationships between paintings. I wouldn’t let these relationships become narrative, because each work has to also be autonomous.

In terms of using historical source material, I always want to discover something in the process of making the work. A lot of the time – for instance in the case of Yvonne Rainer or the Ballets Russes – I am using materials that are hardly obscure. Through the process of adding and removing, the motif appears in the picture plane in a way that addresses the physical and conceptual space simultaneously.

ART iT: The intersection between modern art and dance in your works is thought-provoking. Modern art has been able to establish a degree of universality. When people talk about international contemporary art, they are essentially referring to something grounded in a modernist art historical development. Even though there are of course competing regimes of art, there’s a consensus around modern art as an international language. But modern dance doesn’t seem to have achieved that same consensus. Most people around the world probably associate international dance with classical ballet.

SOP: There are some strands, obviously. The Ballets Russes are the first moment in the history of dance where ballet becomes an avant-garde art form engaging with the reality of its time, as opposed to an affirmative form of entertainment supporting the prevailing power relations, which is what 19th-century romantic ballet was doing. Although his productions were not necessarily a direct reference to political events, once Diaghilev and the company leave Russia they begin to incorporate that experience of exile. Next I would think about George Balanchine and the New York City Ballet in the 1950s and ’60s. He brings modernist ideas to classical ballet while still working within the traditional language. The generation after Balanchine, with choreographers such as Merce Cunningham, Trisha Brown and Yvonne Rainer, develops its own approach to movement, often rejecting ballet training and introducing everyday movement into their work. In the case of Yvonne Rainer, the need to communicate political and social issues more directly leads her to working with film instead.

From that point onwards, things get much more diverse and complicated. I am very interested in a choreographer like Michael Clark, whose work I’ve followed for a while. His choreography is rooted in the language of classical ballet. He uses it as a structure upon which to build his movement, but also to alter and subvert in the process. I think classical ballet is interesting as a complex formal language that relies on the human body as its instrument. This produces a tension between formal discipline and expression that interests me as a viewer and in the way I approach my paintings.

Two Figures (leaning) (2006), watercolor and gouache on canvas, 100 x 120 cm.

Two Figures (leaning) (2006), watercolor and gouache on canvas, 100 x 120 cm.ART iT: This is a bit of an audacious question, but I wonder how you consider your works’ relation to the idea of universality, because I think they exist in an ambiguous space in relation to modernism and contemporary art.

SOP: You mean in terms of being a-historical? Would you say that these paintings are kind of a-historical because of their claim to landscape? I wouldn’t deny that there is an element of timelessness to them, but I don’t think they’re emulating something historical. Maybe they connect to various specific historical points or interests that I have, but I think they’re trying to negotiate how to exist in the present. How to make a landscape painting at this moment in time is the question I am asking myself.

I am interested in specificity as a problematic endeavor for making a landscape painting, or a painting of anything, really. I don’t take it for granted that I can just take a motif and paint it. The question would have to be built into the result in some way, and I hope that my works communicate that. The paintings have a strange physical reluctance, and I always try to approach the process economically without attention to technique. The motif tries to affect the viewer, get her attention and reaction, but this promise remains somewhat unfulfilled and produces a lack that locates the paintings firmly in the present.

ART iT: Could we say they are restless paintings?

SOP: Maybe, yes. I try to approach them without taking anything for granted.

Silke Otto-Knapp: Cold Dark Deep and Absolutely Clear