II.

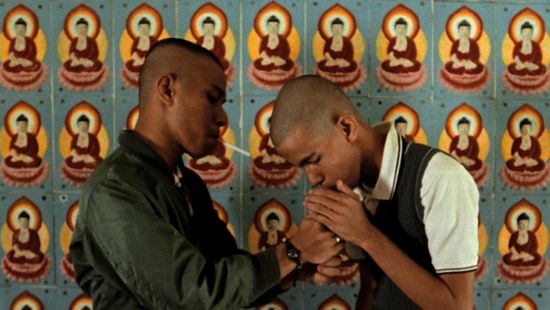

the meaning of style (2011), 16mm film transferred to HD video; color, sound; 4 min 50 sec. All images: Courtesy Shady Lane Productions.

the meaning of style (2011), 16mm film transferred to HD video; color, sound; 4 min 50 sec. All images: Courtesy Shady Lane Productions.ART iT: We were just discussing your marxism today project and how it builds upon and diverges from your previous works and interests. In that regard another work that interests me is the meaning of style (2011). Thematically it continues your early interest in pop culture and subculture, but almost subversively it also appropriates the look of a polished music video. As you say, it almost refuses to be seen as an artwork.

PC: Few of my works look like each other – one thing I dislike with artists is the systematic approach to an exploration of one given thing over 20 years, because I usually find that the commercial imperative sits behind that reductionism. That’s something that doesn’t ring true to me. I always like it when I can’t recognize the artist.

With the meaning of style, in 2007 on a visit to Kuala Lumpur I by chance ended up at a skinhead club. I was following a band from Indonesia called The Brundles, who were playing at a squat club. Seeing all these skinheads there, I couldn’t read what it could mean – a Malaysian skinhead? I couldn’t understand what legacy it drew upon.

I then made several trips back to Kuala Lumpur. First I asked the skinheads several questions: What does it mean to be a Nazi Malaysian skinhead? What are the origins of the subculture in Malaysia? Is there any anger or violence attached to the subculture, and if so, toward who is it expressed?

However, the answers were not articulated in a way that was surprising or compelling. I understood at that point that the work shouldn’t be about a description of the skin. It should be about the image of the skin. Not something about the history of the birth of the skinhead in Britain from 1969 on – which in Malaysia coincides with race riots. In Britain the skinheads were a working class subculture. In the beginning it was about the relationship between white and West Indian and Caribbean working class youth. It was only in the mid-1970s that it became a nationalistic, far-right, neo-Nazi enterprise. And throughout it’s always been a complex and engaging subculture because it’s always occurred in counterpoint with an anti-fascist or leftwing or progressive or radical reading of what that is. But of course it’s also pre-digital and completely analogue. Any moment after 1985 is somehow a staging of something lost. It’s already a rereading of the authentic, which is what skin always attempts to describe.

So the resulting video was about trying to make something that would be about surface and about beauty and about some kind of invitation to think about those themes – not to answer but rather to propose. For marxism today I worked with Laetitia Sadier from Stereolab, the great Marxist pop band. For the meaning of style I worked with the Welsh psychedelic wizard Gruff Rhys, from Super Furry Animals, as well as a band called Y Niwl. So musically it was also about finding something closer to pop video.

the meaning of style (2011).

the meaning of style (2011).ART iT: Does the stylishness of the video then reproduce the way that skinhead culture was absorbed in Malaysia without the social-historical context from which it originated in Britain?

PC: Dick Hebdige’s Subculture: The Meaning of Style is one of the most influential books about reading pop and youth culture in Britain. It was written in the late 1970s and addresses of course Punk and Skin and different sub-cultural styles and how we could read them profitably as ways of being about cultural expression and their radical potentials and conservative limitations – what does it mean to join the tribe? But it’s changed so radically again at this moment. The Internet is a very good way of thinking through how these things break. In the case of a tribe like Emo, for instance, is it merely a rereading of Goth from the 1980s, or is it as distinct as we imagine it to be?

Malaysia of course gained independence from Britain in 1957, but as with other former colonies the troops did not immediately leave. Malaysians went through a classically rigid and brutal British education system with caning and violence and silence in the classrooms and the copying out of lines. I think the troops were still there through the 1970s, and most likely that’s where the musical impulse entered. I’m sure that those concerns voiced by British subcultural music met their own interests in the ghosts or the haunting of post-colonial Malaysia. But it’s also largely a Malay rather than Chinese- or Indian-Malay subculture. It appropriates the position of the white working-class British skin, which is problematic, but interestingly that contradiction is at the heart of the image.

ART iT: I didn’t realize your work had a connection with this idea of British colonialism. Did you get any feedback from when you showed it in 2011 at the 3rd Singapore Biennale?

PC: There was certainly an interest in it in Singapore, because Singapore has such an economically and culturally structured relationship with Malaysia, even though they’re both incredibly distinct at the same time. When you look again at the education and penal systems, for which Singapore is so famous, it seems like a radical extension of the perverse colonial fantasy of canings and floggings and whippings that emerged from Great Britain.

ART iT: And we see it playing out again with the extreme response to the London riots of 2011.

PC: The riots were so interesting in reflecting the punitive weight of the justice system. Putting a teenager in jail for posting on Facebook a call to riot in a small town in the north of England, to which nobody turned up, seems to me a perversion of the cause. What was more surprising was how many people felt that the riots were inexplicable. That the rioters chose consumer objects like trainers and flat screen TVs was deemed unworthy, although to me it seemed entirely understandable, because surely every time someone goes to the shopping mall or supermarket, they also imagine doing that. That’s the heart of the promise of every shop – what if you could take it all? It’s like the TV shows with the “supermarket sweep” events.

But the riots were also without doubt a social expression about the relationship to policing and police in London. It’s no surprise that they came after the shooting of a young man.

Both: soy mi madre (2008), 16mm film transferred to video; color, sound; 28 min.

Both: soy mi madre (2008), 16mm film transferred to video; color, sound; 28 min.ART iT: How about soy mi madre (2008), which borrows its format from the Mexican telenovela to deal with class differences in Mexican society. How far can you push popular genres to contain socially critical messages?

PC: I think sometimes by excising the original impulse from the work it embeds it in a different way. The telenovelas are popular in their drive – they’re not difficult. They’re definitely about a certain form of pleasure. In the case of the telenovela, what is the pleasure of genre?

My film soy mi madre was not about making a mockery of wobbly sets and cheap film. I was looking into the values that melodrama and emotional histories of performance offer, and whether it would be possible to use them to create a critique. All melodrama has critique within it because it’s all about the pain of the social field and the contingency of identity: Why was I born a pauper and you a prince? And what happens if we find out we were swapped at birth by an opiated wretch of a mother who died on a highway?

That’s the terrain specifically of Victorian melodrama, which I researched when I was preparing the work, and of course I’ve watched a lot of Mexican telenovela from the 1980s. There’s a whole series of films from the golden age of Mexican film, in the 1940s and ’50s, which are rereadings of Hollywood dramas in Mexican settings, with the same exquisite staging and settings of Hollywood. These became the basis for a certain kind of melodramatic expression. By the 1990s the telenovela was the biggest Mexican economic export, bigger than tin or silver or oil. They sold to Russia, the Philippines, the Balkans, the rest of Central and Latin America, the US. So they’re quite easy to find in a way. And they have so many twists and turns because of the condensed nature of soap opera that they’re really enjoyable. I approach things because I love them, not because I see them as diminished or demeaning. Yet I see most popular forms as disappointing, because they could be so much more than they are, and why are they not?

ART iT: In making your own version of telenovela were you also trying to promote more critical or even dialogic ways of viewing TV?

PC: I think we already have that to a large extent. That’s part of everybody’s experience of TV. You respond to what you see by saying, “So-and-so would never do that,” or, “That’s incredible!” There’s a strong critical relationship there, even with the news. There’s a critical investment even with the most unlucid of viewers in how much to believe of the address.

I think things like teleshopping and telenovelas and karaoke could be so much more, and it’s strange that they become these reduced and reproduced forms when they could offer almost anything. You could have political speech karaoke, couldn’t you? Or alien poetry karaoke. There’s no reason not to go out on a Friday and do any of those things, because they could be great fun. Instead we sing Backstreet Boys and Boyzone and Brittany.

Pt I

Phil Collins: Production and Reproduction and Relations of Production