IN AND OUT OF ARTICULATION

By Andrew Maerkle

Still from Answer Me (2008). © 2011 Anri Sala, courtesy the artist; Galerie Chantal Crousel, Paris; Marian Goodman, New York; Hauser & Wirth, London, Zurich; Johnen/Schöttle, Berlin, Cologne, Munich.

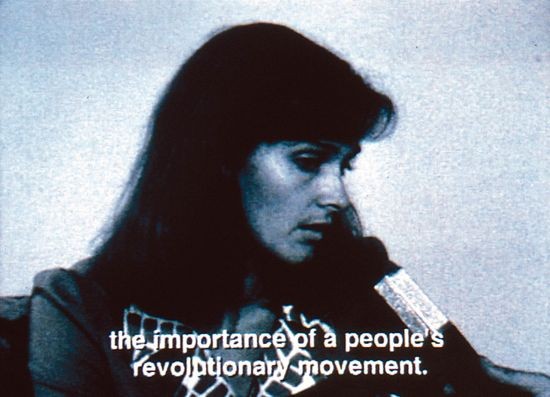

Still from Answer Me (2008). © 2011 Anri Sala, courtesy the artist; Galerie Chantal Crousel, Paris; Marian Goodman, New York; Hauser & Wirth, London, Zurich; Johnen/Schöttle, Berlin, Cologne, Munich.Anri Sala first came to widespread international attention through his short film Intervista (1998), in which the artist discovers old 16mm newsreel footage of his mother giving a speech and an interview at the 1977 Albanian Communist Party Youth Congress, and then attempts to reconstruct his mother’s words from the soundless images. In its investigation of language and syntax, its attentiveness to the dynamics between absence and presence, past and present, and its ambivalence toward the possibility of conclusive meaning, Intervista established a number of creative threads that have unspooled in different directions over the course of Sala’s career. In particular, recent films such as Air Cushioned Ride (2007), in which a car circling a row of freight trucks in a parking lot finds itself receiving different radio signals at different points along the course of its circuit, and Answer Me (2008), in which the acoustics of a geodesic dome influence a conversation between estranged lovers, combine image and sound to underscore the physical subjectivity of our intellectual experience of space, and the body’s constantly moving position in processes of communication.

ART iT met with Sala at his studio in Berlin, where he was preparing for concurrent exhibitions in Japan at the National Museum of Art, Osaka, and the Kaikai Kiki Gallery, Tokyo, respectively, to learn more about the relations of articulation that drive his works.

I. Phases/Gradations – Light/Dark; Violent/Peaceful – and Rupture

Anri Sala on the dynamics between syntax, form and content in his films.

Still from Intervista (1998), color video with sound. © Anri Sala, courtesy the artist and Galerie Chantal Crousel, Paris.

Still from Intervista (1998), color video with sound. © Anri Sala, courtesy the artist and Galerie Chantal Crousel, Paris.ART iT: I imagine many of your interviews start with this work, but what strikes me about Intervista (1998) is that it revisits a specific historical moment in Albania’s Enver Hoxha regime (c 1943-85) through an almost abstract interest in language and modes of communication, with the history structuring the language in the film and the language providing a filmic structure from which to view the history. Your subsequent works have seemed to engage in varying degrees of specificity and formal experimentation, alternately moving more toward one extreme or the other. Is this balance something that you approach conscientiously?

AS: I think Intervista is a good place to start because of these two directions present in the work, or more specifically, because there is an intersection of two interests that are both important for me, one being content and the other being syntax. We tend to take syntax for granted or forget about it because it appears to be transparent, and it’s only when you consciously think about it that you realize in this transparency there is also a rigid structure. Intervista is about a moment in Albania when, due to its ideological responsibilities, language became so stiff that it could not adapt to political and social changes. Instead of getting massaged into a new state of mind, language simply broke down, in the process revealing its mechanics.

For many people, what is interesting and touching is the narrative aspect of Intervista, but this can obscure the role of syntax in the film. For example, there’s a moment when my mother questions whether she really said everything that we reconstructed from the found footage. She’s not trying to deny any political agenda, because at the time it was clear to everybody what one could and could not say, and also because in a way she still believes in what she said. Rather, what she is unable to recall is the syntax of the language at the time, because she can no longer accept it as a given.

This interest in how the structure of language can reflect structures of power has remained important in my work. Syntax also became important because of my desire to avoid getting trapped in the transparent syntax of artistic convention. In the works that followed Intervista, I concentrated more on dealing with syntax rather than content, which was also a way to create room to escape the fixed expectations of other people. Since then, I have alternated between combining the two to varying degrees.

I would say there are four films in which I’ve explicitly worked with language: Intervista; Nocturnes (1999) [which juxtaposes interviews with two insomniac recluses, a fish enthusiast and a former soldier]; Dammi i colori (2003), in which language plays a surrealistic role because it describes the future, or a political conviction of how the future should be, such that the reality of what is being said cannot be proven, which is similar to Intervista; and Overthinking (2007), in which I interview the spirit of the Mexican muralist David Siqueiros through the aid of a medium. In this last instance the result was straightforward in that it’s just a filmed conversation and the work does not have the complex structure that I have used for other videos, but here again language has the potential to both open up inaccessible worlds and to deceive.

Still from Lakkat (2004), color video with sound, duration 9 min 44 sec. © Anri Sala, courtesy the artist and Galerie Chantal Crousel, Paris.

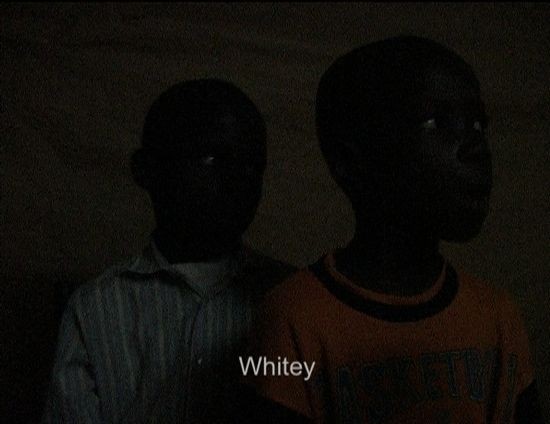

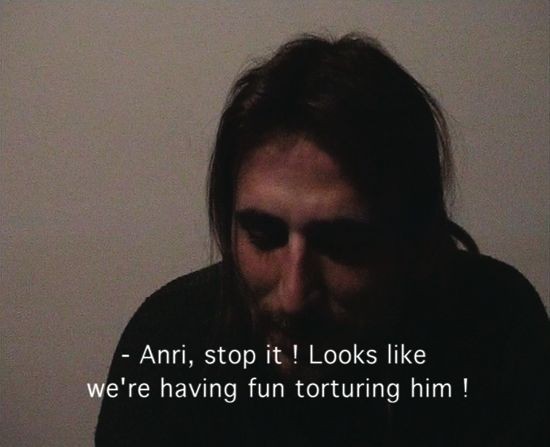

Still from Lakkat (2004), color video with sound, duration 9 min 44 sec. © Anri Sala, courtesy the artist and Galerie Chantal Crousel, Paris.ART iT: The works you mention deal with language strictly in terms of discourse, but you also have works that further explore the limitations of semantics, such as Lakkat (2004), in which children are taught Wolof words related to lightness and darkness, and Promises (2001), in which four young Albanian men each attempt to repeat the line, “Nobody puts a price on my head and lives,” attributed to the American gangster Al Capone.

AS: That’s true. Promises has to do with the impossibility of saying something, when the last of the four men struggles with the idea of even speaking the sentence, and it also addresses syntax because the men are not native English speakers, so another guy plays with the ambiguities between “lives” and “leaves,” which reflects the social context in Albania at a time when many people were intent on leaving the country to seek better livelihoods elsewhere.

Lakkat is also related to syntax because it produces content by association – not directly, because the words are presented one-by-one; and not taken out of context, because the words come with a lot of context already, but rather because you gradually realize the children don’t understand the full significance of the words they are being taught. For example, in the beginning of the video one boy has trouble saying a word correctly and, with his mispronunciation of just one consonant, the meaning shifts between “very light” and “eating.” And what I found fascinating during my research was that because of the racial politics of colonization, and the visualization of the social hierarchy along gradations of lightness, Wolof has many words for the differences between white and black, yet all the other basic colors are named with French loan words.

The actual shooting of the film was only one part of the project, which continued for several years with the translation of the audio into different languages for subtitling. Ultimately I produced a UK English version and a US English version in addition to a French version, purposely working with people who are not professional translators: the cultural theorist Stuart Hall in the UK; the post-colonial theorist Homi Bhabha in the US; and the Chadian poet Nimrod in France. I did this because I wanted to underscore the awkwardness of languages in regard to translation. For example, the Wolof word toubab is almost untranslatable into French because its counterpart has such a racist connotation, while in UK English it was translated as “whitey,” and for the US version as “Great White Hope.” So instead of only translating the language of Lakkat, the project is also a translation of different relations to colonization.

Interestingly, in the US the phrase “Great White Hope” originates from attempts by the white establishment to produce a new white boxing champion after Jack Johnson became the first black man to win the world heavyweight title in 1908. A former champion, James Jefferies, came out of retirement to challenge Johnson, and lost. So the phrase was first associated with racist enterprise, then with white shame, and this ambivalence of meaning is analogous to the shifts over time in the connotation of the word toubab in Senegal, which otherwise is such a difficult concept to translate. For me, the subtitling was not just the usual process of bringing a film to an international audience. If subtitling is usually an exteriorization of the film, in this case it became a kind of interiorization.

Still from Promises (2001), color video with sound and English subtitles. © Anri Sala, courtesy the artist and Galerie Chantal Crousel, Paris.

Still from Promises (2001), color video with sound and English subtitles. © Anri Sala, courtesy the artist and Galerie Chantal Crousel, Paris.ART iT: You talk about the deceptive transparency of syntax, but you also seem to employ varying degrees of opacity in your works. For example, in Lakkat this aspect of working with poets and critical thinkers on the subtitling, as opposed to translators, is not evident to the average viewer. With Promises, too, the vital difference between “live” and “leave” in the context of post-Communist Albania is not so apparent, since the men are all filmed in the same nondescript interior setting.

AS: Certainly. Life in Albania at the time was very violent because there was a vacuum of law and order: everyone was welcome to be violent in a way. It was almost like a cowboy film, except that there was always a very real threatening presence. What happened with the last of the four men was that he refused to succumb to the virtuality of the cinema-style language. He took the whole thing very seriously. He was not worried about whether his accent would be good or whether he would sound dangerous or believable. For him, saying the line was an almost philosophical question: Do I believe in violence? It’s not that everything was black-and-white – it’s not like you were risking your life everyday – but if you were a young male going out to bars or going to school and so on, you had to choose how to engage with that violence. And at that point in life when your philosophical syntax is not fully developed, you can incline more toward one way, or the other. We all had these fantasies of becoming wilder or tougher or more threatening, but we were also reading books and exploring new ideas, so we knew there was an alternative. For him it was a philosophical statement not to play the game of violence in the street, and that carried over into the virtual realm of the video. The work ultimately crosses all these levels in the relations between identity and language.

ART iT: In the 1990s I was a student in Washington, DC, when it was known as the “Murder Capital of the US,” and had a similar experience. I remember balancing an intellectual curiosity that I wanted to pursue further – but which could also be perceived as being unmanly – with a desire to be considered as tough as the next man, even though I was far on the periphery of any actual violence.

AS: Exactly. In Albania it depended on who was around you, although there were also people who could combine both the curiosity and the toughness – I mean, we necessarily had to be able to combine the two.

Part II. Orientation, This

Anri Sala discusses the choreograpy of perception in time and space.

Anri Sala: In and Out of Articulation